Honoring Black Resilience Through the Black Homesteader’s Project

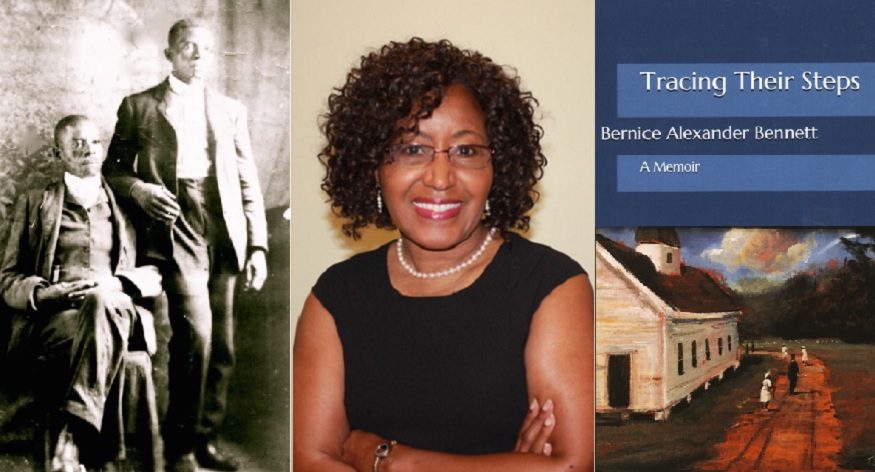

- By Bernice Bennett ·

Juneteenth is a special day of celebration honoring the anniversary of the emancipation of enslaved communities in Texas on June 19, 1865. It’s a day to reflect on the past, but to also look forward and honor the resilience of African American communities.

In that vein, I’d like to share my own family’s story and an exciting historic initiative called the Black Homesteaders Project which is part of the Homestead National Historical Park Service.

In the midst of the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln proposed new legislation called the Homestead Act of 1862. The idea was to offer, for a minimal fee, up to 160 acres of public land to any citizen willing to farm the land and become a “homesteader.” After 5 years, the homesteader earned the right to own the land outright.

The law was unique in that it did not discriminate on the basis of color and was notable for the opportunity it gave African Americans to own land. The U.S. government passed the Homestead Act to encourage western migration.

Every citizen in “good standing” was allowed to apply to become a homesteader, and for newly emancipated African Americans this initiative became a way to establish their lives as free citizens.

My grandmother told me that the land where she grew up in Louisiana was owned by her grandfather, Peter Clark. This inspired me to look into his story.

Through the documentation surrounding Peter’s application to become a homesteader, I not only confirmed that he applied to become a homesteader on April 25, 1887 and was issued his land patent in 1896, I also learned fascinating details about him and the life he led in 19th century Louisiana. Through his application testimony, I learned the exact location of the homestead and that he had already established residence on the land 10 years prior. He had a house, an outhouse, and 5 fenced-in acres that he had cleared.His testimony continues, “My wife and 4 children have lived there continuously since first establishing residence.”

When asked about the character of the land, he described it as “Piney-woods land — most valuable for farming when cleared.”

Several years later, Peter traveled back to the New Orleans office to update on the land and he provided the names of five witnesses who could attest that he successfully performed what was required of him as a homesteader. In 1894, the names of the individuals were published in the Southland newspaper.

![Article listing Peter Clark’s homestead application and names of witnesses [Credit: The Southland Newspaper, October 17, 1894.]](https://blog.myheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/image8-6.png)

Article listing Peter Clark’s homestead application and names of witnesses [Credit: The Southland Newspaper, October 17, 1894.]

I also found a document stating that Peter didn’t have the money to go in for his final testimony, and had to wait until he’d saved enough to complete the process. Finally, in 1896, his patent was issued and his claim to the land was approved. Peter’s extraordinary stories have been documented in my award-winning book, Tracing their Steps: A Memoir.

You can watch me tell my story and reveal my research, and hear stories of other descendants who I was able to help, in this Nurturing Our Roots Genealogy Discussion:Discovering the story of my ancestors’ land ownership inspired me to help others learn about their own ancestors’ stories. Many people who have inherited land are not familiar with their family’s history of land ownership. Through the Black Homesteaders Project, many descendants were able to trace the lives of their ancestors during this pivotal time in history. This Project initially focused on the Black Homesteaders of the Great Plains and now descendants of Homesteaders throughout the United States are also researching and sharing their stories. Read more about their inspiring stories in the National Park site, Black Homesteading in America.

If you think your ancestors may have acquired their land through the Homestead Act, I recommend visiting the Bureau of Land Management, where you can find records of the landowners. This is where I found my great-great grandfather’s name listed, along with some of the aforementioned witnesses. I have also started a new Facebook group called Descendants of African American Homesteaders that offers helpful tips and important information.

Happy Juneteenth!

![Photo of Peter Clark and son Moses [Credit: Bernice Bennett]](https://blog.myheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/image3-17.png)

![Peter Clark homestead application [Credit: Bernice Bennett]](https://blog.myheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/image5-19.png)

![Peter Clark Homestead application [Credit: Bernice Bennett]](https://blog.myheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/image7-8.png)

![Document listing Peter Clark’s witnesses [Credit: Bernice Bennett]](https://blog.myheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/image6-8.png)

![Peter Clark’s homestead patent [Credit: Bernice Bennett]](https://blog.myheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/image2-22.png)

![Peter Clark’s final homestead certificate registration [Credit: Bernice Bennett]](https://blog.myheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/image4-16.png)

Janice Gilyard

June 18, 2021

Excellent article! Thank you.