Thank you for sharing this. It’s very interesting and helpful.

Contributing author Schelly Talalay Dardashti is the US Genealogy Advisor for MyHeritage.com

Your family name has evolved since it was adopted. It may represent your family’s sojourns in different countries; its spelling and pronunciation may have changed, and it may have been changed following a recent immigration (although not at Ellis Island).

Your family name has evolved since it was adopted. It may represent your family’s sojourns in different countries; its spelling and pronunciation may have changed, and it may have been changed following a recent immigration (although not at Ellis Island).

Other factors are easy to understand. Spelling wasn’t engraved in stone, people were illiterate or not literate in the language of a specific area. Our ancestors didn’t know how to spell their names and government officials were responsible for recording the names in registers or in important documents.

WHY IS IT SO HARD?

The official wrote the name the way he heard it. Perhaps the official was elderly and deaf in one ear, or your ancestor had a speech impediment or an accent. When your ancestor’s cousin came in to record a later birth, however, a new younger official sat behind the desk, one whose hearing was excellent and the cousin spoke clearly.

When immigrants moved to a new country, they often changed their names. They wanted to make it easier for themselves, their neighbors and employers to spell or pronounce their names, and for official documents. If the original names were written in other alphabets – such as Cyrillic (Russian, Bulgarian etc.) – they were phonetically transliterated into English, providing many new spelling possibilities. Accents or dialects further complicated the choices.

When specific letters or combinations of letters in an original language could not be understood properly in a new language, the immigrant tried to simplify it, but variations can be traced to those with difficult-to-understand accents and imperfect knowledge of English, in the case of U.S. immigrants. Thus, a name was pronounced one way and recorded another way. In fact, a search of a family through listings in city directories might show how the immigrant kept changing his or her name. My great-grandfather, whose original name was TALALAY or TALALAI or TALALAJ (all said the same way), used TOLINE in his petition for citizenship (and explained why it took me years to find it!), changed to TOLIN and finally to TOLLIN, while his brother adopted TALLIN.

Immigrants sometimes felt that if they translated their name, it would be simpler. It might have been as easy as simply translating the old name into the new language. In Israel, a family named Mandelbaum (almond tree) in Europe may have selected Shaked (almond in Hebrew). Some immigrants wanted a complete break from their former lives, or they may have been escaping from conscription in the old country and were still afraid of officials who might come looking for them. That alone was enough reason to adopt a new name.

At some periods in certain countries, some people were forced to adopt surnames imposed on them. When able, they’d drop the new names and return to the original or a “better” one in their subjective opinion. Others wanted to avoid persecution and, to hide their nationality or religion, adopted less-ethnic names. At certain times in Europe, for example, some marriages were not recognized by the civil authorities (although couples had religious marriages). Thus, registrars recorded the children’s family name as the mother’s maiden name. Upon immigration, the person began to use his or her father’s name.

WHAT TECHNIQUES HELP?

Searching for variations and permutations and eventually locating the original name takes time, sometimes lots of time. Here are some tips:

Don’t just read the name silently, speak it and try to spell it phonetically. Ask others to speak the name. Try this experiment: ask a young child to write the name as you say it. Their phonetic interpretation may be helpful.

Try to translate the name back to its original language using an online translation site or dictionaries. If possible, check surrounding countries or in the case of Eastern Europe and its changing borders, see what the name is in various languages used in one geographical location.

Names beginning with H or a vowel need attention. Depending on the language, the H may be dropped or changed to G or even an A, and a name that begins with one vowel may begin with any of them; A/O or I/E or O/U are common vowel substitutes. Check all possible variations.

Be careful with Eastern European-origin names beginning with J – this could also be transliterated as I, E or Y; a final E, S or Z may have been dropped or added; there may be one or two Ns at the end or one or two Ms in the middle.

When working with indexes, human error may be the culprit. Transcribers suffer from eye strain, put their fingers on the wrong keys, even write in the wrong column. I’ve seen records where the field was “Marital Status” and the answer was “Russian” – an obvious error. A transcriber might transpose certain letters. Try to see the possibilities by writing down the name. Under it, write various transpositions of all the letters, including the first letter. Other errors are easily understood by looking at your keyboard, where nearby letters are confused when fingers are placed on the wrong keys.

When thinking about alternative spellings, try prefixes, suffixes and different endings.

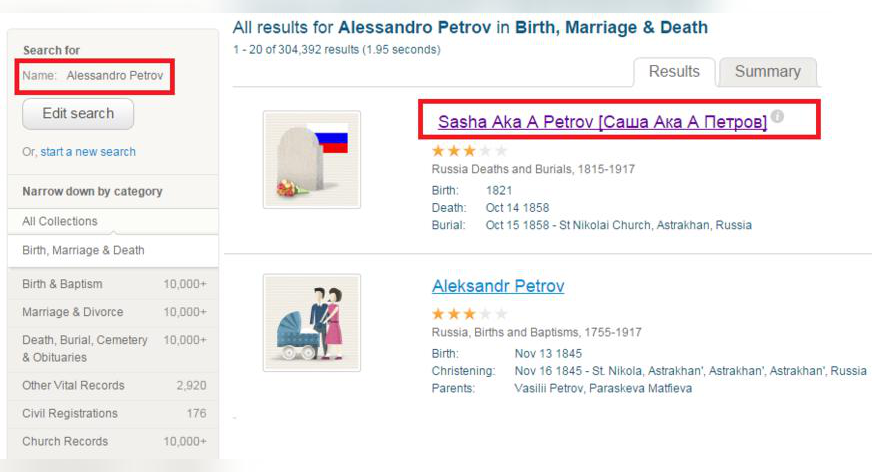

When you search online, always choose “sounds like” or “alternative spellings” or “Soundex” to increase the returns and possible success. When using SuperSearch, MyHeritage’s powerful search engine, you’ll see many alternate names from which to choose.

A search for Alessandro in Italian brings results in Russian for "Alexander and the nickname "Саша/Sasha" (Click to Zoom)

If you are dealing with immigrants to America, however, please do not believe that your ancestor’s name was changed at Ellis Island. Nearly every genealogy conference offers a lecturer addressing this great urban myth. Not one case has been documented where an immigrant’s name was changed by an official at Ellis Island. The person may have adopted a new name the minute he or she walked out the door, but it wasn’t changed by an official on Ellis Island, where some 60 languages were spoken, and many clerks were also immigrants.

Passenger manifests were prepared in Europe by staff who understood many languages, and these manifests were used by Ellis Island staff to merely check off the passenger as he or she went through Ellis Island.

In 1898, one of my family’s first immigrants arrived. Mendl Talalay (who became Max Tollin) changed his name from TALALAY to TOLLIN, and wrote home about it. Those who followed also adopted the new name almost immediately. The story surrounding the change is that Mendl/Max was told by a fellow traveler – who spoke some English – on the ship, that he would have to change his name immediately as no one would give a job to Mr. Tell-a-lie. Each of our immigrant ancestors told this story to their children and grandchildren. Most TALALAY adopted TOLLIN or TALLIN, although there are some other variations.

Do you have a story about a name change in your family? Share your stories, questions and comments. We look forward to reading your comments right here.

Frankie Klen

August 7, 2015

This was an interesting story, I’m sure it will help me in finding some names in my family. I did notice that 1 thing was not mentioned, hyphenated names. I’ve been going through Slovakian church records for almost 2 years and noticed that many families sometimes show up with their last name hyphenated and other times it’s one or the other name, both men and women. It looks like when there is a large family or a common last name some people will hyphenate their last name in order to know what family line they are from and if they are related. At least that is what I have seen for Slovakia in the church records for the town Sedliacka Dubova. I’m not sure if this is common or if other countries have done the same thing but I’ve looked at just 1 towns records from the late 1700’s to early 1900’s because this is where my family is from.