What Is a Census Record and How Does It Trace Your Family History?

- By admin

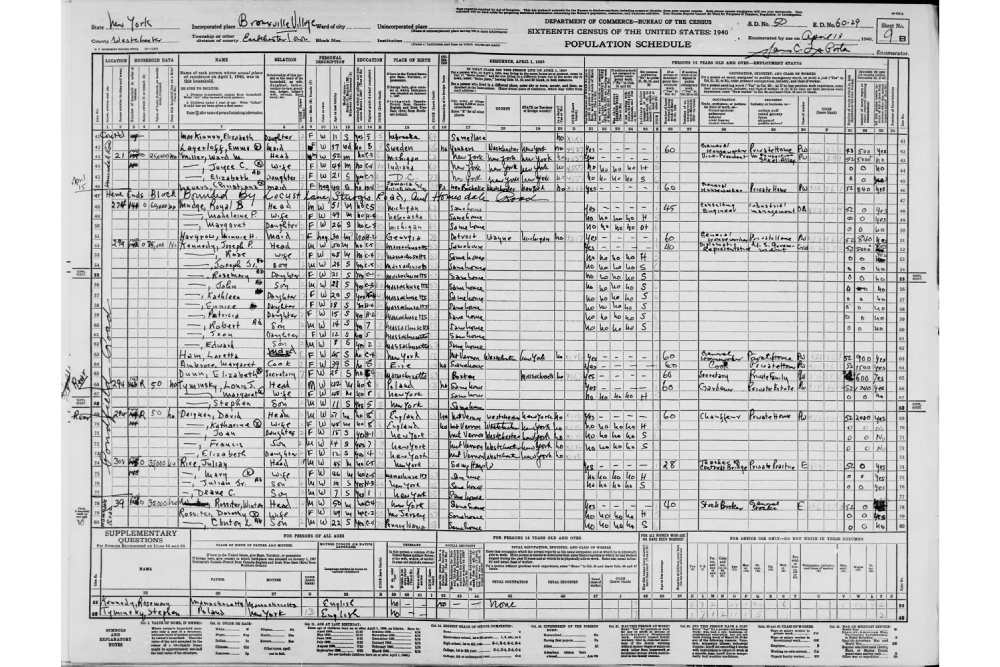

In a representative democracy like the U.S., a census record helps the country decide on resource allocation, fair voting districts, and effective emergency response. The government usually conducts it every 10 years to count a nation’s population.

But this large gap creates a snapshot in time that can miss population shifts and life changes. Travelers, temporary residents, and the inherent limitations of a single moment in time can lead to undercounting.

While you can manage the discrepancies by looking at surrounding years, the process becomes difficult if the ancestor moved frequently or had life changes during the period. Below, we’ll explain how you can overcome these hurdles and trace your family history.

Key takeaways

- Beyond names and ages, census records can show migration patterns, family structures, and even clues about social standing.

- Privacy laws restrict access to recent data, and early records often lack detailed information. Missing records due to disasters or gaps between censuses can also make tracing ancestry challenging.

- Birth certificates, obituaries, and city directories can fill gaps left by missing censuses. Looking for clues in surrounding records and considering reasons why information might be missing can also aid your research.

- By piecing together information from multiple censuses and other records, you can learn about where your ancestors lived, who they lived with, and how their lives changed over time.

The limitations of census records

Variations between countries

Record-keeping practices vary depending on the place and period. In the U.K., households often filled out forms — called schedules — themselves, giving them some control over what goes into the document. On the other hand, U.S. enumerators traditionally recorded details directly that might’ve led to misinterpreted data.

Privacy laws may also limit the information that could identify individuals. The U.S. restricts public access for 72 years. This means that as of 2024, the latest census available is from 1950. The U.K. enforces a stricter 100-year wait.

Note: The U.S. and the U.K. conduct censuses every 10 years — decennial. Other places, like France, do them every five years, which we call quinquennial.

Inline HTML

Changes over time

Early censuses — like the first one in the U.S. in 1790 — had very few details. Enumerators recorded only men who were heads of the household by name.

They categorized everyone else by race and gender:

- Free white males of over and under 16 years (to assess the country’s industrial and military potential)

- Free white females

- All other free people

- Enslaved individuals

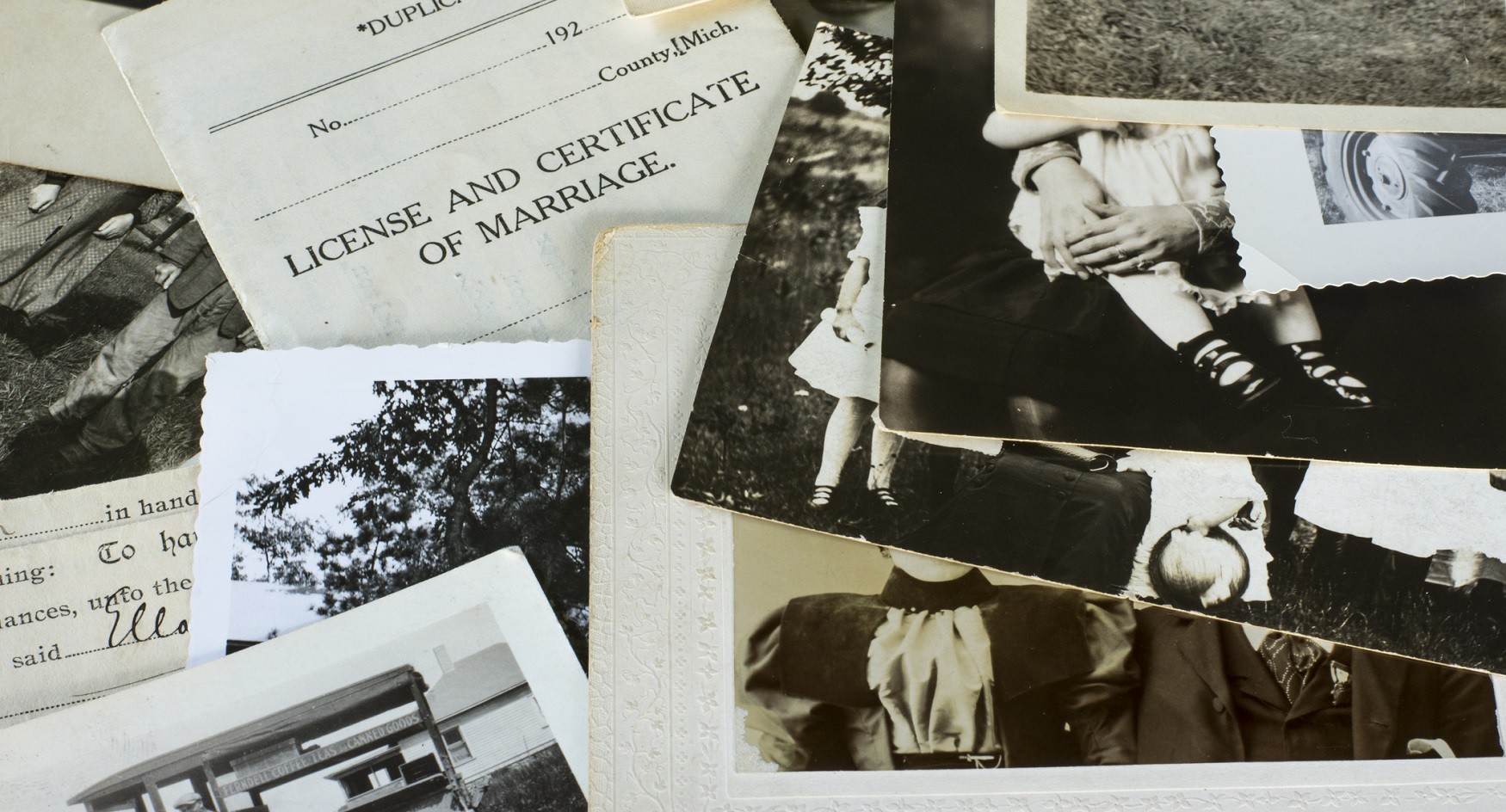

If you’re looking for someone who lived during this period, you can try birth certificates, property records, and draft registrations. These could have clues about name changes, relocations, or childbirths.

However, the 1800s population boom forced governments to revamp record-keeping. Simple headcounts in censuses gave way to detailed information like names, ages, genders, and family structures.

Later ones also emphasized tracking naturalization, reflecting growing concerns about immigrants. The 20th century’s immigration surge prompted the addition of data like the country of origin and citizenship status.

Missing census records

Fires, wars, and natural disasters can leave significant data gaps, making it harder to track ancestors. For example, a fire that erupted in 1942 destroyed the U.K. census for 1931. But just because some information is missing doesn’t mean there’s none available.

The U.K. compiled a 1939 wartime register specifically for identification and rationing purposes. Although not a perfect substitute, it may offer valuable insights into the population.

Additionally, many municipalities like New York City conducted their own surveys between national ones. The 1891 police census can fill the gap left by the lost 1890 federal one — which was damaged in a fire in the commerce department building in January 1921. You can check with local archives or historical societies for these documents.

Here are some additional resources you can use when census records are lacking:

- Birth and death certificates can pinpoint a family’s location during those events.

- Obituaries contain details about the deceased’s residence and surviving relatives.

- City directories and phone books can list residents for specific years and locations, even if a census is missing.

- Voter registrations may reveal a person’s home at a particular time.

» Learn to research genealogy in disaster zones

How to follow your family tree through census records

Beyond basic facts, censuses can reveal uncommon names, unexpected migration patterns, or atypical social standing. Here’s how you can use these files to explore your lineage:

1. Start with the name

Start by establishing your ancestor’s first, middle, and last name. Immigrants often adopted anglicized versions to help them integrate better and make it easier for English speakers to pronounce their names. For example, “Sam” may represent various Italian names like Salvatore or Santo.

Some censuses lacked explicit gender identifiers, so relying solely on names can be misleading. For example, a poorly written “O” or “A” could turn Rosario (a man) into Rosaria (a woman) or vice versa. You can use wildcards. (* and ?) to capture these nuances — e.g., “Rosario,” “Rosari?”

In other cases, people’s nicknames can sound unisex. A man named Antonio or Antonino could have spelled their nickname “Toni” with an I, which you can easily confuse with a woman’s.

Tip: To confirm gender, look for clues in relationships listed in the census, such as “daughter” or “nephew.” Additionally, you can check other documents like ship manifests that might explicitly state it.

2. Look at migration patterns

Another crucial step in your search is to determine the birthplace that appears in a census record. If you explore a file and see that the birthplace doesn’t align with the one on the birth certificate, the ancestor might have moved.

For immigrants, the U.S. files between 1900 and 1950 used “Al” for aliens and “Na” for naturalized citizens. Later ones offered a “Yes” or “No” option. If you still can’t locate them, expand to the surrounding households listed in the census. Look for families with individuals born in the same country or sharing familiar surnames. These could be relatives like in-laws, siblings, or cousins.

For large-scale migrations, delve into U.S. immigration data for the region and track arrival patterns. Identify peak years and research the area’s history during the time. For example, you can look for economic downturns or social unrest that might’ve triggered mass movement.

Additionally, enumeration districts — the geographical zones in censuses — may also help. Overlay these areas with historical maps to visualize your ancestors’ potential migration paths. This technique works especially well for large-scale events like the Dust Bowl exodus or the Great Migration.

Tip: If you have a hunch about an address, the unified census ED finder can help pinpoint the specific enumeration district for that location during a particular census. Knowing the exact geographical zone can narrow your search and save you time and effort.

3. Explore family dynamics

Changes in marital status across different censuses unravel family dynamics. A child might appear as “single” in one file but show up as “married” in the next alongside a new person. You can also see the number of years a couple has been in wedlock, the age when the ceremony took place, and if they had spouses before.

Identifying new adults of the opposite sex in a household can be a clue to potential in-laws. For example, grandchildren and children may be adopted. It’s crucial to confirm any suspected relationships with information from other vital records, particularly birth and marriage certificates.

These abbreviations can help reveal family relationships:

- X (Children under 10)

- W (Wife)

- DW (Dwelling vacant, such as a child that left for college)

- HOH (Head of household)

- SON (Son)

- DIL (Daughter-in-law)

- FIL (Father-in-Law)

4. Use census clues from the enumerators

Enumerators, the people who collected household data, often left notes and markings. For example, circled crosses might reveal who answered, while other notations could indicate immigration status or age discrepancies.

These enumerator notes can also clarify early records’ quirks, like side street names. Even vacancy notices or participation refusals paint a picture of population relocations and community dynamics.

You may also find out if a house was under construction, recently abandoned, or temporarily unoccupied. This can offer clues about neighborhood movement: Were people moving in or out? Did occupancy fluctuate seasonally? Etc.

Note: MyHeritage offers indexed census data and scans of the original census cards. This means you can see the entries, including notes the enumerator took.

Confirming census data accuracy

The very nature of collecting vast amounts of data from diverse populations introduces errors. Forgetfulness, especially among older enumerators, can lead to age discrepancies.

They also might have used “heaping,” rounding the ages to specific endings. For example, someone listed as 30 in 1880 might have been born between 1849 and 1850. Systematic over- or underestimation might also occur.

Boarders or lodgers might be left off, marital statuses changed, or occupations disguised by those wishing to elude law enforcement. Individuals fearing detection might misreport details like relationships, names, or ages.

A single record offers a glimpse into a specific time, but don’t expect a complete picture of your ancestor’s life. Still, there are steps you can take to ensure more accurate research:

- Build a family profile: Create a list of all children in the family, along with their birth years.

- Consult vital records: Find birth and death certificates, marriage records, and any other sources. They will help you determine who would likely be alive and living at home during a specific census year.

- Analyze census counts: Compare the number of children listed in the census record to your expected number based on the family profile.

- Investigate discrepancies: If the census count differs from your expectation, it might be because of:

- Children who died young: Check death certificates for children who might not be on your initial list.

- Children who left home: Research if children might’ve moved out for work, marriage, or other reasons.

- Boarders or lodgers: Consider the possibility of additional people living in the household who weren’t documented.

- Enumerating errors: Illiteracy, language barriers, and misinterpretation by the census taker could also be factors.

- Deliberate omission: Determine if your ancestors might’ve had motivations to omit information — avoiding authorities, social stigma, etc.

Minor inconsistencies, especially age discrepancies attributable to memory lapses, are less concerning as long as the overall picture aligns — living where expected, with known family.

» Explore the 1950 U.S. census on MyHeritage for free

Rethink your roots and trace your family history

Few records show the picture of a family in a neighborhood that a census can. They go beyond basic details, revealing their relationships, social circle, and economic standing.

The information might not always align with what you thought you knew about your ancestors, but it can help you better understand your identity.

Remember to verify all research findings with additional records and documents. The cross-referencing helps ensure the accuracy of conclusions and gives you a more complete look at your ancestors’ lives.

MyHeritage empowers your investigation by providing a massive collection of records and powerful indexing tools. You can refine your search by name variations, nicknames, or relationships within the household, saving you hours of sifting through irrelevant entries.