I have come across many discrepancies and mistakes I know from documentation I have. People didn’t always tell the truth either for whatever reason. Makes it a challenge for sure.

For the Record: Watch out for errors

- By Schelly

This post is written by Schelly Talalay Dardashti, MyHeritage’s US Genealogy Advisor.

Human beings do make mistakes. Remember the old proverb: ‘To err is human, to forgive divine’? Genealogy’s version should be: ‘To err is human, to correct genealogical.’

Every family historian and genealogist knows that family trees may include errors.

Sometimes they are due to simple human mistakes. These may be due to recording data heard orally, or via transcription or copying from other records or details recorded in error due to tragic events, such as deaths, which might skew relatives’ memories, or even because of bad handwriting. Sometimes errors result from information provided by relatives who just did not know the truth (such as gravestone errors) or realizing that the correction will be too expensive (again, gravestone errors). Occasionally, the reason can be chalked up to ‘let’s make the story sound better,’ which may lead to additional embellishment as years go by.

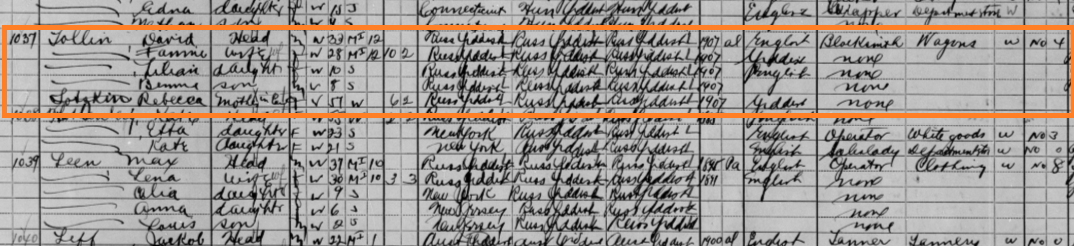

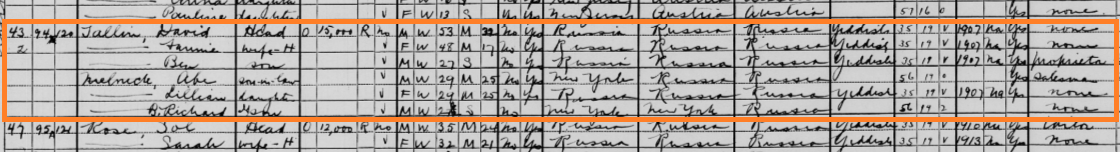

Here are some examples showing what might have happened – a 1904 Border Crossing record; 1910, 1920 and 1930 US Federal Censuses – for my TALALAY family, which became TOLLIN after immigration.

1904 Border Crossing From Canada to the US

Aaron Talalay listed as Tallarly arrived from the UK on the SS Canada to Montreal. He took the Dominion railroad to New York in November 1904

When my great-grandfather Aaron Peretz Talalay entered the US from the UK (where he stayed for a few months) via Canada in November 1904, he was listed as Aaron Tallarlay. His wife, Riva, and children Leib (Louis), 2, and Chayeh Feige (Bertha), 9 months old, arrived in New York City in December 1905. He was born in 1873 and his age is correct, 31. Riva was born in 1875. As you will see, their ages seem to be wrong in all the census records below.

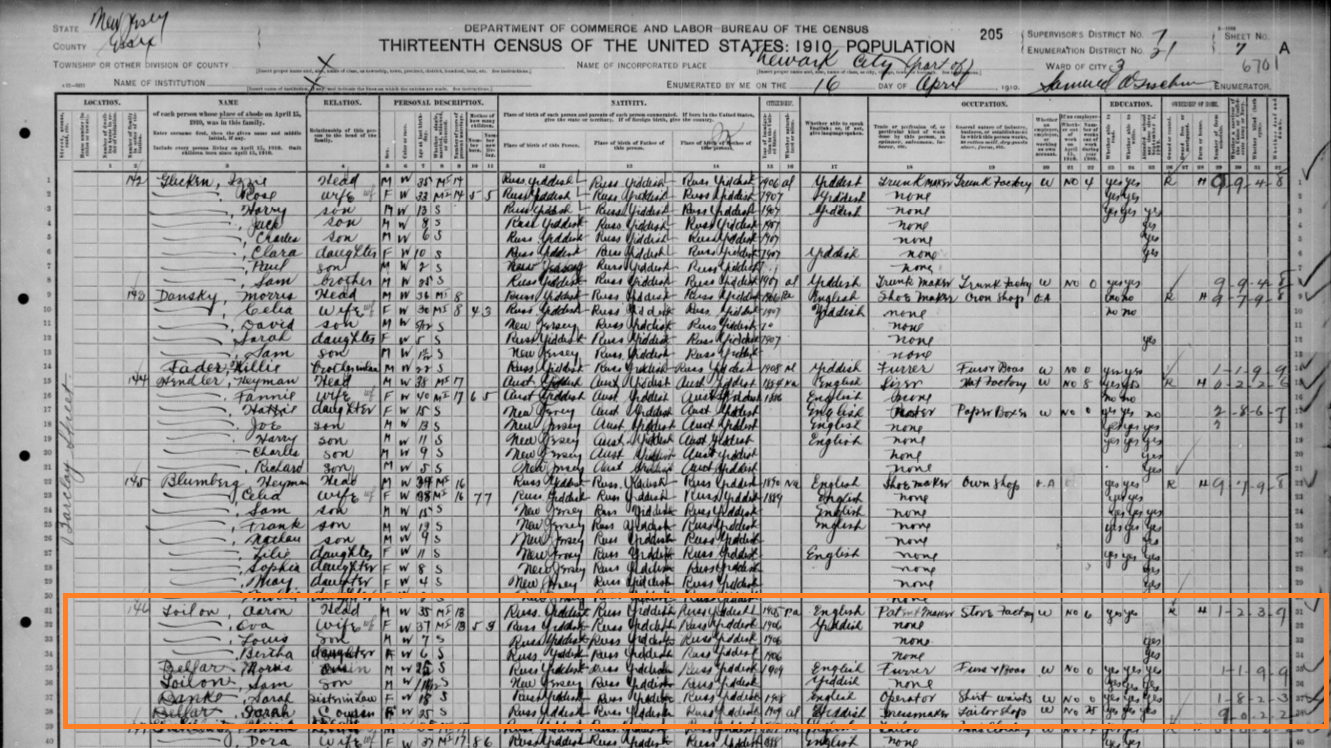

1910 US Federal Census

TOLLIN is spelled TOILON or LOILON on the 1910 census! I have no idea who the Beller cousins are…yet!

In the 1910 Census, the family was listed (and indexed) as LOILON, although whether the initial letter was a T or an L is debatable. The record was found only by looking at record after record to find a likely couple. I believe my great-grandparents would have said TOLLIN, the enumerator heard TOYLIN and spelled it TOILON. My great-grandmother Riva (or Rebecca) is listed as Eva. It shows Aaron arrived in 1905 (it was 1904) and the family arrived in 1906 (it was 1905). Their ages are listed as 35 and 37, but the correct ages are 37 (Aaron) and 35 (Riva).

In 1915, when the family became naturalized citizens, the record was in the name of TOLINI. It took years to find the papers! I begged a friendly county clerk to go up into the storage area to pull the record by offering to pay for dry cleaning her clothes after dealing with the dust and creepy crawlies up there.

1915 New Jersey State Census

In the 1915 New Jersey State Census, the name is indexed as TOLINI, but spelled TOLIN. And great-grandmother Riva (Rebecca) is now Rose. NOTE: If the state you are searching conducted censuses, they are extremely helpful in recording changes in residence and family composition as they were done between the Federal censuses.

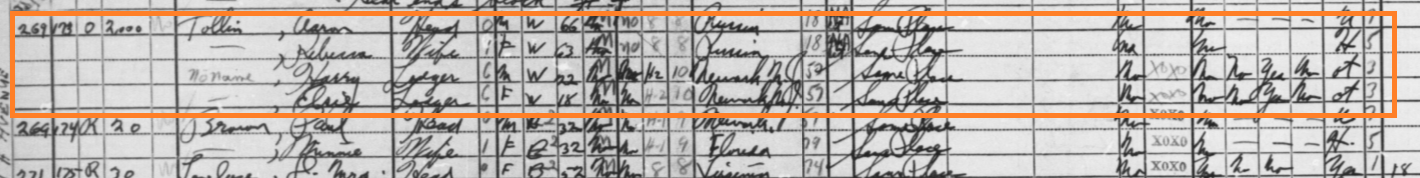

1920 US Federal Census

In the 1920 Census, the family is now listed (and indexed) as TOLINO – making them seem Italian – and my great-grandmother is now Rebecca. In addition to Louis and Bertha, there are another three sons. Bertha is listed as 14 (she was 16). The parents’ ages are listed as 45 and 40 but they actually were 47 and 45.

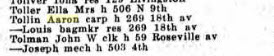

1923 Newark City Directory

Finally, in 1923, the spelling has stabilized!

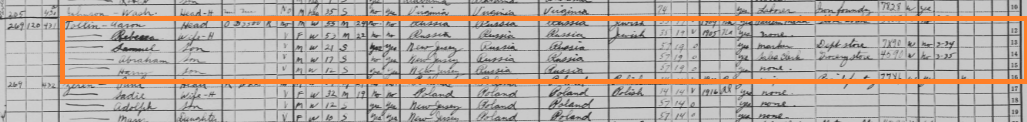

1930 US Federal Census

In the 1930 Census, this family is finally TOLLIN, as were all the other relatives in Newark, New Jersey and Springfield, Massachusetts. Bertha is not listed as she was married and living in New York, while Louis had finished medical school and was in Baltimore, Maryland. The parents were listed as 55 and 53, but they were really 57 and 55.

1940 US Federal Census

In 1940, the composition of the family has changed somewhat as most of the children have married and are living elsewhere. The youngest, Harry, and his wife are living with them.

And, just to make things a bit more interesting, Aaron’s brother David and his family arrives and decides to spell the name TALLIN. They only lived a few blocks away from each other, and no one knows why David decided to use that spelling.

A great tool available to everyone with a MyHeritage tree is our Consistency Checker. It scans our family trees to identify potential errors, conflicts, and inconsistencies. Some are relatively obvious with children listed as having been born before their parents, siblings born four or five months apart, mothers listed as age 8 or 80 and having children. We can all make mistakes but the consistency checker finds these errors for us. It also alerts us to many additional discrepancies and, once fixed, will improve the quality and accuracy of our family trees. Read more about this extremely helpful feature at: Online Family Tree Consistency Checker.

Here are some tips to avoid repeating and compounding errors in your research.

How to avoid compounding and repeating mistakes

– Do try to always view scanned images or photocopies of vital records, such as birth, marriage and death certificates. A transcription of that information might contain human errors, misspelling, number transpositions and other errors. If using online sites with collections of scanned images, look at the image – not the human-generated transcription. For most of us, the scanned images are as close to the original as we can get.

– While census records are always useful, remember that the enumerator might not have correctly understood the heavily-accented English of a family, and this may have lead to mistakes in ages, names, origins.

Try to follow the family through the subsequent censuses to determine the facts. In the US, also try for state censuses (if they exist), social security records, draft cards, alien registration cards, voting records and citizenship papers.

– If given a choice between using scanned/digitized/microfilmed images of any type of record or a transcription made by another person, check out the image yourself. Human error may creep in every time a record is copied. In addition, transcription also relies on judgment calls made by someone who may not be aware of certain common ethnic names or places or someone who does not have proper training in deciphering handwriting for certain errors or countries. While the transcribers try to be accurate, the information may not be, so look at the image yourself.

– Historic newspaper articles can be important but do remember that the reporters might have interviewed individuals who were hazy on details, or the reporter did not know enough about a possible situation to investigate thoroughly – this happens even at the best of newspapers. A published obituary may also rely on previously made errors and thus perpetuate the mistakes.

– Family trees published or online are only as good as the person who compiled the tree. Was the researcher methodical, follow genealogical standards, check original documents (or images), re-check transcriptions? Or did the compiler merely record the family stories and present them as facts without verification of events, dates, names, etc.? Does the compiler give verifiable sources for data?

In the same way, a published family history (or even a geographic history, such as a city, county or state) may also contain errors repeated from previous compilations of family trees. Read through online family trees and family histories and look for the documented sources used by the author or compiler. Published histories might also contain printer errors.

-You are fortunate if your ancestors left letters, journals or even day-by-day diaries. Although these are considered a valuable primary source, even some of the ‘facts’ about individuals might be based on hearsay.

– Remember that certain events might not have been recorded accurately, particularly if negative events might impact a person’s reputation. On the flip side, however, stories about persons already considered to have negative reputations might be compounded to make their stories even more colorful.

– Genealogy or family history magazine articles have usually been checked and sourced, although a story might rely on an index or human transcription with possible errors.

– Many sites today offer scanned images and these are as good as seeing the original material. One caveat is that a certain document might have notes or comments on the back that might have been overlooked during the scanning process. Always try to use additional documents to confirm data on individuals and families.

– If, despite all your best efforts, you cannot confirm information as the sources offer conflicting data, record all those sources showing the data in each. At the least, it will confirm to others who view your work – and to your future descendants – that you were aware of the conflicting data. In the future, additional records might come to light to settle the conflict once and for all.

Have you found errors in relatives’ family trees? How did you handle the conflicting information? Did you contact the original compiler of the tree? Have you shared documents indicating the correct data? I’d be interested to know how you handled the situation.

Terry Taylor

July 17, 2018

Indexing is only as good as the person’s skill in deciphering handwritten documents so, yes, looking at the image is very important. My favorite (and most obvious) example of a recording error in the imaged document itself was a census record of my mother-in-law’s family. She was the youngest of the children and the only one born in the U.S. The entire family was listed with their countries/places of birth. Everyone except Ruth was born in Russia. Ruth’s birthplace was correctly listed as Michigan, but then the places of birth of her parents were listed as Pennsylvania and Wisconsin! (Remember they were listed on the lines above hers with Russia as their place of birth.) I imagine that the census taker realized later that two spaces were left blank and without much thought filled them in with whatever. Makes one wonder what else happened in the recording of that data.