History as Told Through Ellis Island and Other New York Passenger Lists

- By Talya

In addition to being New Year’s, today marks the 128th anniversary of the opening of Ellis Island. In honor of the occasion, we revisited one of the most popular historical record collections on MyHeritage — the Ellis Island and Other New York Passenger Lists, 1820–1957. The collection charts the millions of immigrants who arrived in New York and includes information such as name, age, gender, occupation, destination, and information regarding place of origin.

So what can we learn from the New York passenger lists spanning more than a century?

The graphic below is a data visualization of the top male names among the Ellis Island and Other New York Passenger Lists, 1820–1957 for each decade between 1850 and 1950. It opens a fascinating window to the events of this tumultuous historical period.

Watch the visualization here:

The visualization also reveals some surprising facts about who was traveling during this period and why. Many people believe that there’s no reason to search passenger lists for ancestors who were already in the U.S., but this graphic shows that that’s not true: many of the travelers and crew members from the 1900’s onwards were actually U.S. citizens.

Here are some of the historical events reflected in the visualization:

1840s: Ireland’s Great Famine

The first thing you may notice about the graphic is that the top four names of male passengers from 1840–1850 were Irish. This makes sense in the context of Ireland’s Great Famine, also known as the Potato Famine, which lasted from 1845–1849. The famine was sparked by a disease that attacked potato crops, destroying a major source of nutrition and livelihood for many Irish people, but was exacerbated by a number of political factors. The resulting starvation caused the Irish population to drop by 20–25%, making it one of the deadliest events of the 19th century.

Over the course of the Famine, around 650,000 Irish immigrants arrived in New York harbor and by 1850, U.S. immigration records show that 43% of the foreign-born population was Irish.

Depiction of ship preparing to sail from Ireland to America during the Irish Famine (The New York Irish, 1996)

It stands to reason that all those Johns, Jameses, Pats, and Thomases arrived in New York seeking a better fortune and hoping to send their earnings home to their struggling family members.

Learn more about Irish immigration and Irish genealogy in the aftermath of the Great Famine.

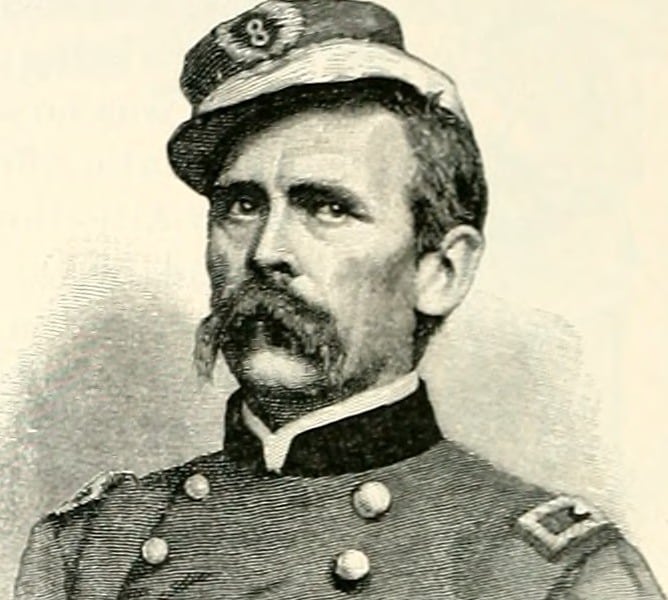

1860s: The Civil War

As we advance toward the 1860s, we see this wave of Irish immigration decreasing as more British Johns and German Carls pass through Ellis Island. It turns out that more German-Americans enlisted in the Union Army to fight against slavery than any other ethnic contingent. More than 200,000 German-born soldiers served in the union army. Historians believe they enlisted in such high numbers because slavery reminded Germans of the serf system under which they had suffered in their homeland.

After fleeing Germany for being a revolutionary, Louis Blenker became a brigadier general in the U.S. Civil War, image from “Battles and Leaders of the Civil War,” 1887.

1890s: The Italian Exodus

Heading into the 1890s, Antonio from Italy enters the scene, followed closely by Giuseppe. Following the unification of Italy in 1861, the country experienced economic hardship and political and social unrest, pushing an estimated 13 million citizens to leave the country between the years 1890–1915. 4 million of these Italian emigrants came to the U.S., where there was a growing market for unskilled labor that required little to no English language skills, such as construction and factory jobs. As we see in the graphic, the wave of Italian immigration peaked in the 1910s. Almost half of the immigrants who arrived between 1905 and 1920 ended up returning to Italy, having saved enough money from their work in the U.S. to live more comfortably in their home country.

![Mulberry Street Market, Little Italy, New York City, 1900 [Credit: Photocrom print by Detroit Photographic Co.]](https://blog.myheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/Mulberry-1.jpg)

Mulberry Street Market, Little Italy, New York City, 1900 [Credit: Photocrom print by Detroit Photographic Co.]

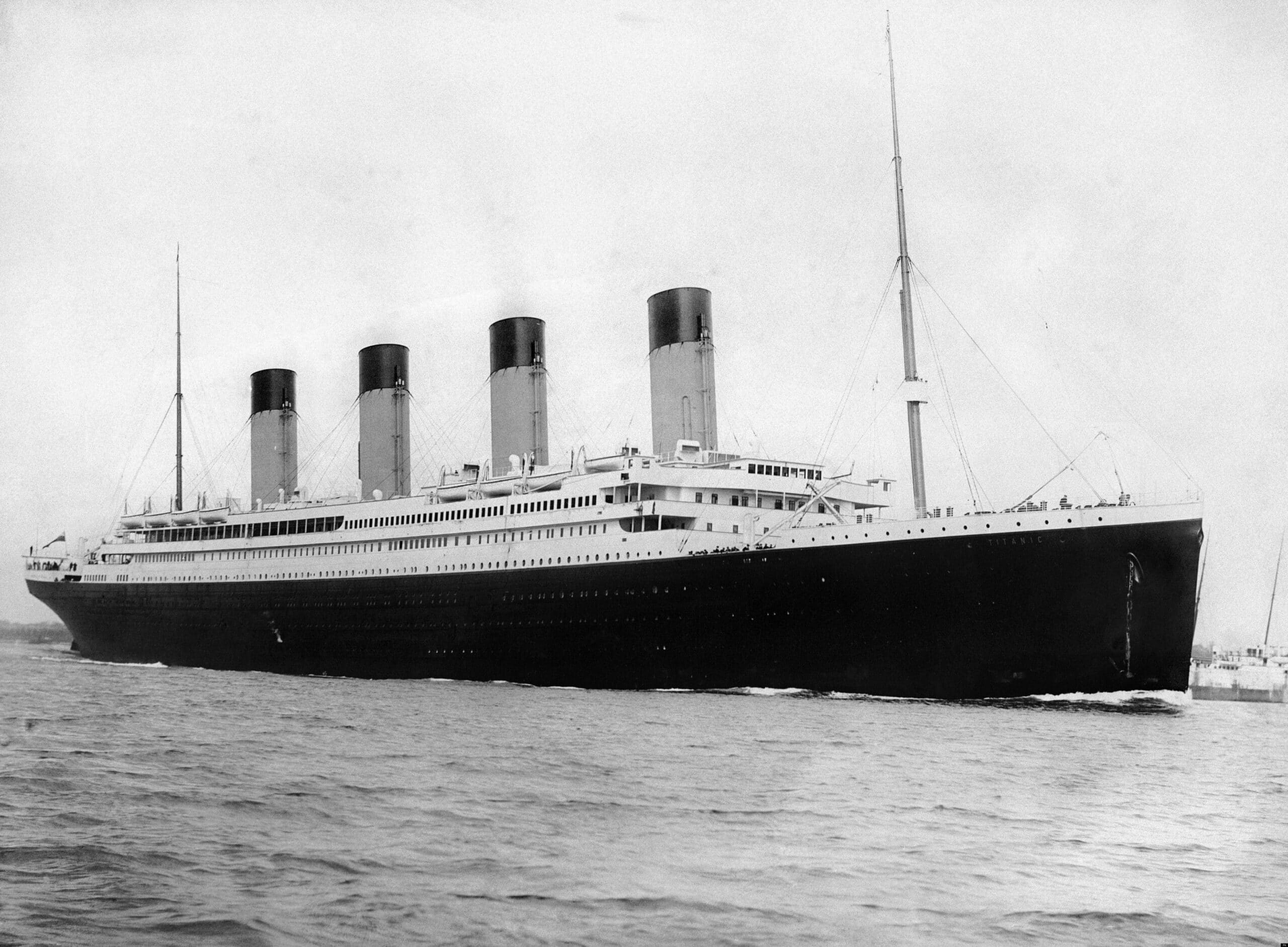

1900s: The evolution of travel

We see a fascinating phenomenon starting in the 1900s: an American name enters the graphic. This tells us that it wasn’t only immigrants who were traveling to New York. It was also American citizens returning home.

With the great technological advances of the late 19th century, traveling by boat became faster, cheaper, and easier. This increased mobility made the concept of a “two-way ticket” more feasible and affordable — and people began to travel with the intention of returning home.

As a result, traveling for leisure became a mark of status, and passenger ships began to cater to wealthy Americans who sought adventure in distant lands. These were the first luxury liners, built to provide a comfortable, fast, and safe travel experience with fine dining. The Titanic, which sank on its maiden voyage in 1912, is an infamous example.

1920s: Immigration reform

In the aftermath of World War I, the U.S. government began to place restrictions on immigration from certain regions, due to an increase in xenophobia and fears over the effects of immigration on the economy. In 1924, the government passed an Immigration Act that banned all immigration from Asia and placed a tight quota on immigration from countries outside the Western Hemisphere.

In the graphic, we see a sharp drop in the diversity from previous decades, with British names dominating the chart. This trend continues into the 1940s. Unfortunately, this restrictive immigration policy particularly affected Jews from Central Europe, and the U.S. provided them little to no refuge from Nazi Germany leading up to and during the Holocaust.

1950s: Aftermath of World War II

In the 1950s we see two international names jumping back up on the chart: Jean from France and Giuseppe from Italy. In 1948, the United States passed the Displaced Persons Act, finally opening the doors to war refugees from Europe.

Passenger John

John remains the most common name among passengers during almost the entire period of 110 years — with a brief capitulation to William in the 1920s, though that’s not counting the American Johns on the list at the same time. It remained one of the most common names throughout not only among U.K., U.S., and Irish passengers, but also among French, German, and Italian passengers (named Jean, Johann, and Giovanni, which are all versions of John).

![John Muir, also known as the “Father of the National Parks”, immigrated to the United States in 1849 from Scotland [Credit: UC Berkeley, 1907]](https://blog.myheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/John_Muir_Cane-1.jpg)

John Muir, also known as the “Father of the National Parks”, immigrated to the United States in 1849 from Scotland [Credit: UC Berkeley, 1907]

A captivating snapshot of history

The slice of data displayed in this visualization provides a captivating and unconventional snapshot of U.S. and European history. It also shows us that passenger lists can be valuable resources for everyone, not only descendants of immigrants.

Bruce

January 23, 2020

Excellent research…my family on both sides were immigrants…