His Father Went Missing in WWII. 82 Years Later, He Got a Gift from Him Thanks to MyHeritage

- By Elisabeth Zetland ·

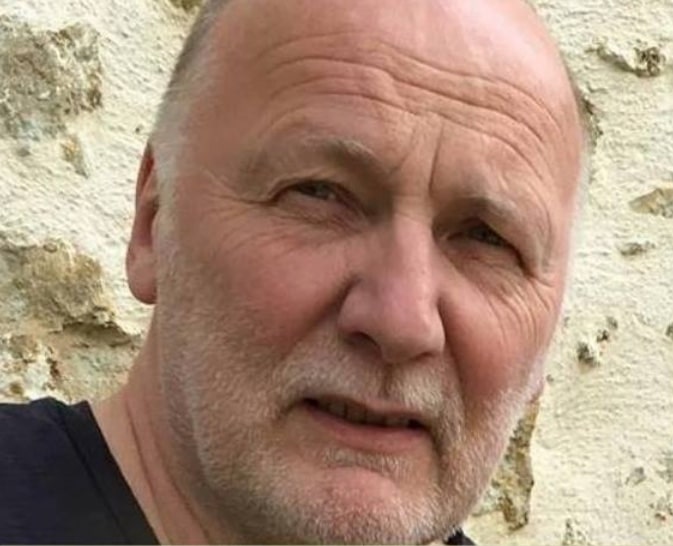

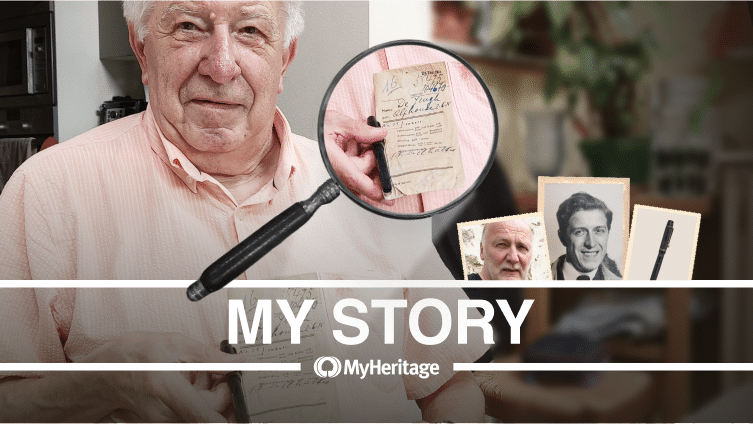

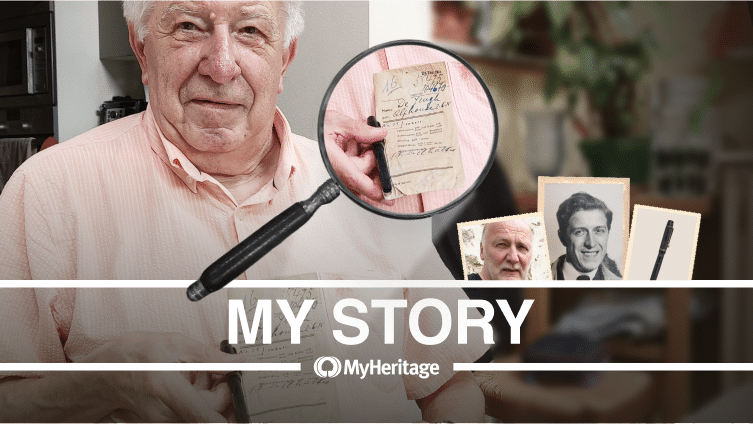

When Pierre Painblanc, a Belgian user from southwestern France, found a bilingual French/Dutch message in his MyHeritage inbox, his curiosity was immediately piqued. This is not the usual genealogical mail between two users investigating their relationships. The sender, Ellen de Visser, a Dutch journalist, explained to him that she was looking for the descendants of a Belgian resistance fighter, arrested and deported by the Germans during World War II.

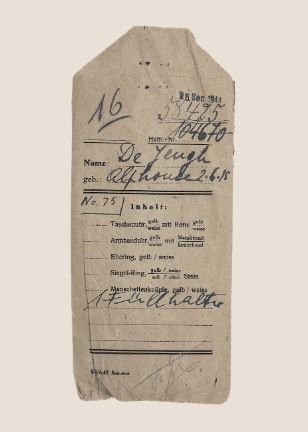

In the Dutch archives, Ellen had found an envelope with the name of a certain Alphonse De Jongh. The envelope also contained various things: his date of birth, his camp number, and his signature, but most importantly, it contained a fountain pen, which Ellen wanted to return to the family of the deceased. And it was through a MyHeritage family tree — Pierre’s tree — that Ellen had just found traces of Alphonse’s descendants.

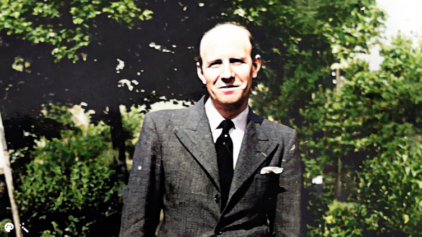

The fountain pen Alphonse De Jongh was carrying when he was arrested in 1941. National Monument Kamp Amersfoort

Pierre says: “My uncle went from one camp to another and his name was misspelled several times. Furthermore, his Belgian nationality was incorrectly copied and became Dutch, which explains why the documents about him were located in the Netherlands, instead of having been sent to Belgium after the war.”

A fountain pen kept in the archives for 80 years

“As soon as the war ended, my aunt did research to find her husband,” says Pierre. “It was in vain. Ellen was the first to assume that the name had been spelled incorrectly; De Jongh had become De Jonck, then De Jeugh. While searching on MyHeritage, she came across my tree. It’s extraordinary!”

“My cousin was born two months before his father’s arrest, in 1941,” says Pierre. “I figured it might come as a shock to him, and when I called him, I delivered the news gently. At 82 years old, he obviously did not expect to receive such news. For him, there was no hope of finding traces of his father, and suddenly a window opened. Then I gave Ellen the green light to go to Brussels, where he lives.”

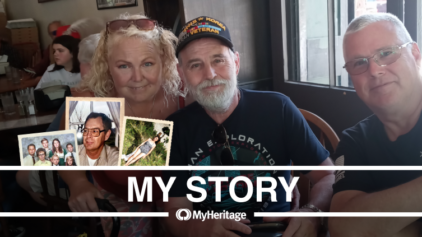

“This is the first present I’ve ever received from my father.” Edouard De Jongh holds the envelope and his fathers’ fountain pen in his hand. Photo: Ellen de Visser

Ellen de Visser, health editor of the Dutch newspaper Volkskrant, began researching World War II artifacts held in Dutch archives because her own grandfather was a resistance fighter in the Netherlands. Arrested in December 1944, he died in the Neuengamme camp.

“This is where my fascination with the Second World War began,” says Ellen, “especially when I saw how many documents about my grandfather were preserved in the archives. Hence this initiative for the Stolen Memory, concerning property confiscated by the Nazis.

“My grandfather was able to leave his wedding ring with my grandmother just before boarding the train. She always cherished it and kept it on her finger with her own wedding ring. It was the last thing she received from him. So I can really understand how important these items are to families.

“I started this project when I realized that there were still unreturned objects in German archives. After the war, many objects were found in the Neuengamme camp in Germany. The British had compiled a long list of the goods they had found. Once certain of the prisoner’s nationality, they sent the objects back to his country. So after the war, I think 2,000 to 3,000 items and envelopes were sent to the Red Cross and the Dutch Ministry of Social Affairs.

“Dutch authorities then tried to find relatives in order to return the objects. The property, for which no family has been found, was preserved in the Dutch archives.

“At the beginning, we therefore had nearly 70 envelopes divided into two archives (the German archives of Arolsen and the Dutch archives). Sometimes the names on these envelopes are barely legible, but luckily there are also dates of birth. I knew there were families who would be very happy and moved to receive these items.”

“I also knew that 80 years later it would be very difficult,” says Ellen. “Most of the prisoners did not survive the war and many of them did not have children. Some were not married, so we are looking for nephews, cousins…”

A deportee found in a family tree

“Three volunteer researchers joined me and we started searching all the archives on the Internet,” says Ellen. “When I got to the MyHeritage website, I was amazed by the number of family trees. MyHeritage helps us a lot: if Pierre had not built his tree on this site, I would not have found Alphonse’s son. I sent a message to Pierre via the MyHeritage inbox, and he responded straight away. It worked wonderfully.”

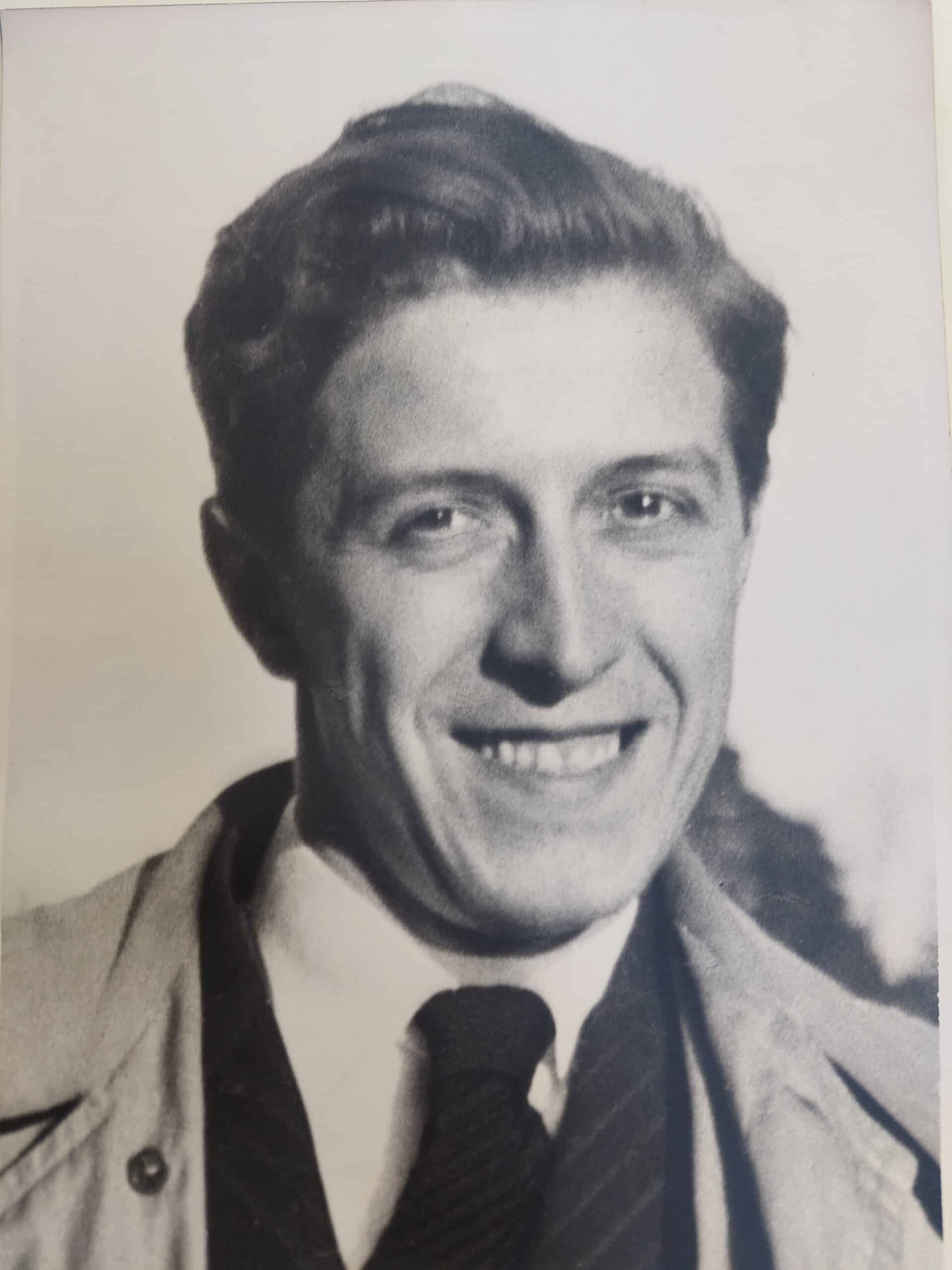

Edouard De Jongh was 2 months old when his father was arrested in September 1941. He had been sent to his grandmother because his parents were fearing a visit from the Gestapo.

He says: “My father was arrested at home, and my mother was almost arrested with him. She played the piano, and a Wehrmacht officer, seeing her sheets, noticed that she played German composers. He deduced that she was not anti-German and that is how my mother would have avoided arrest: thanks to music!”

Alphonse De Jongh had joined the Secret Army — an armed organization within the Belgian Resistance — in August 1941. Married to Marthe Painblanc since the previous fall, the couple had welcomed their first child in July. Alphonse had time to distribute the clandestine newspaper La Libre Belgique and carry out various arms transports before being arrested by the Wehrmacht on September 23, 1941. Transferred first to the Saint-Gilles Prison in Brussels, he was then deported to Germany as a Nacht und Nebel political prisoner. He passed through the following camps: Brauweiler, Bochum, Hameln, Esterwegen, Lingen, and Sachsenhausen.

‘It’s the first present I’ve ever received from my father’

“My father was curious about everything and had a passion for entrepreneurship. He had a keen sense of patriotism, which naturally led him to become a resistance fighter,” explains Edouard. He continued his acts of resistance inside the camps. Numerous testimonies from his campmates attest to this. He had a taste for other cultures, and even Germanic culture, to the point of writing to my mother, in the rare letters allowed, that their son should learn German later, despite everything. He had a great aptitude for languages. He must have certainly distinguished himself in some way by understanding German. He was a visionary and foresaw the evolution of countries, despite Nazism, towards a broader Europe.”

The circumstances of Alphonse De Jongh’s disappearance remain a mystery: his traces were lost in September 1944. Years later, posthumously, he was mentioned in the Order of the Day for the following reason: “Volunteer of the Reserve Mobile, Grenadier Troop, since April 1941. Always demonstrated dedication to his leaders. Carried out various weapons transports and regularly attended all weapons training meetings.” The citation, signed by the Commander of the Secret Army, continues: “Had exemplary conduct during interrogations and in the harsh life of the camps. Was reported missing from the Sachsenhausen camp after forty months of courageously endured suffering.”

“After the war,” continues Edouard, “my mother kept hoping he would come back. With a lot of courage and just one typing diploma, she became a businesswoman! She passed on to me the values that she shared with my father to create and maintain a better world.”

After 80 years, the fountain pen that Alphonse De Jongh had with him when he was arrested has returned to Belgium. Thanks to the family tree containing his name, Ellen de Visser was able to return it to his family: “I keep my father’s pen, which still works, with great care. It’s the first gift I received from my father,” confides Edouard De Jongh.

The restitution project is not completed. There are still around twenty names to find.

Ellen de Visser adds: “We are continuing our research on MyHeritage. We were able to build a family tree for several prisoners. This gave us a lot of additional information, and this way we can continue our research. This is very meaningful work. When I return an object, people are so happy. It’s very moving and very inspiring. Sometimes it’s just an empty wallet or a few pieces of paper, but for them, it’s the whole world.”

Many thanks to Ellen, Pierre, and Edouard for sharing this incredible story with us. If you’ve also made an amazing discovery on MyHeritage, we’d love to hear about it. Please share it with us via this form or email us at stories@myheritage.com.