Beautiful and heartbreaking. Best wishes to Dario and Vittorio and their families.

Signed, Your Father in a Nazi Prison: An Extraordinary Collection of Letters

- By Daniella

The BBC recently published a piece about a remarkable story the MyHeritage Research team stumbled across in 2015. At the time, the team was hard at work searching for Jews from the island of Corfu, as part of a project to reconnect the descendants of a Jewish family of Holocaust survivors with the residents of the island that had given them refuge.

Sometimes, you search for one treasure and dig up another. That is what happened when Roi Mandel, head of the MyHeritage Research team, met Dario and Vittorio Israel — and they pulled out an astonishing collection of letters their father had smuggled to them from a Nazi prison during the Holocaust.

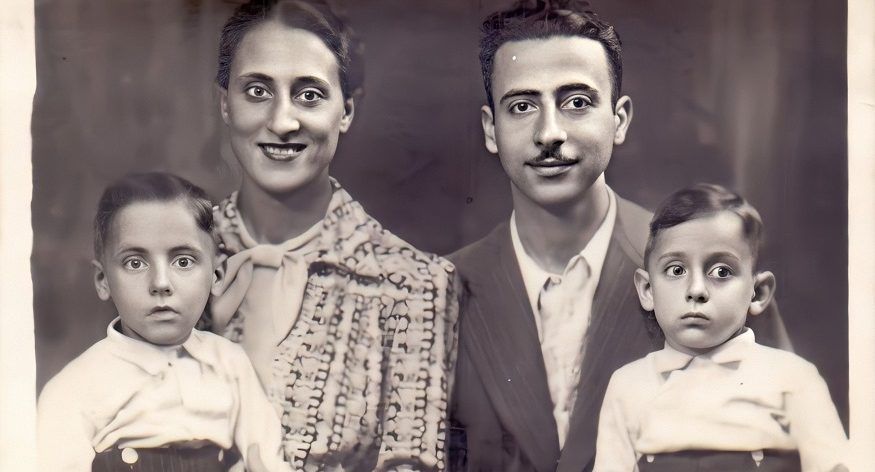

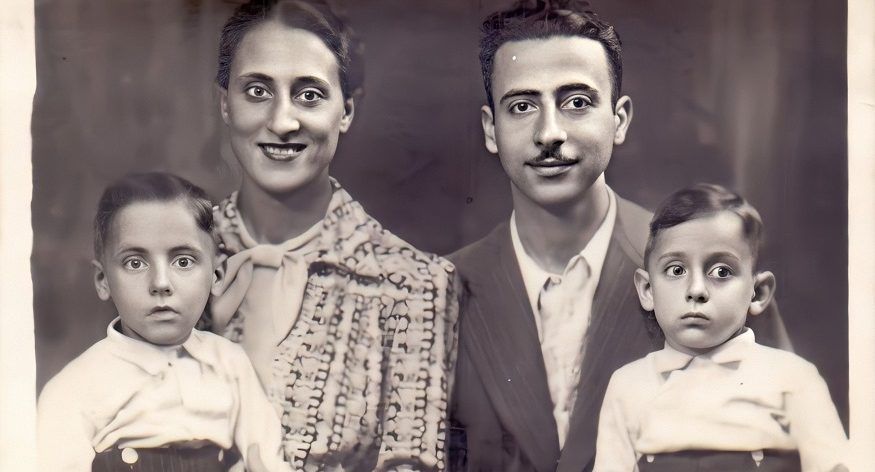

Dario and Vittorio lived in Trieste, Italy with their parents when the Germans occupied the country in 1943.

Their father, Daniele, was concerned about the safety of his wife and children and sent them out of the city, hoping things would calm down eventually. When Daniele was arrested in his upholstery shop on December 30, 1943, Dario, Vittorio, and their mother Anna returned to the city and went into hiding in a woodshed that belonged to Anna’s brother-in-law, who was a Catholic carpenter. The woodshed was cramped and had no light or water — just a small skylight in the roof. The family spent the next 8 months of their lives in this tiny space.

During this period, Daniele and Anna maintained a secret correspondence by sewing letters into the collars and cuffs of Daniele’s shirts as they were taken back and forth from the laundry. Anna carefully saved each and every letter he sent — all 250 of them.

The letters bring to light a detailed and heartwrenching account of the 8 months Daniele spent in the Coroneo prison in Trieste.

Smuggling the letters

Daniele was an upholsterer, and therefore very skilled with a needle and thread. Whenever he had a dirty shirt to send to the wash, he would tear the seams, carefully conceal the letters, and sew them up again. Two of Daniele’s non-Jewish former employees would pick up his laundry and deliver it to Anna at great personal risk. Anna would search for the letters, unstitch the collars and cuffs, take out the letters, and read them aloud to her sons. Then she would wash the shirts, write her own replies, and stitch them in before sending the clean shirts back with her husband’s former employees. Sometimes, she would also send ink, paper, or food that Daniele had requested.

Dario and Vittorio, who were 8 and 9 at the time, anxiously awaited each letter.

Maintaining a correspondence under the noses of the Nazis was no simple matter. The German authorities knew that Daniele had a wife and two sons and they regularly pressured him to reveal their whereabouts. They drilled him about it every week, and sometimes even tortured him in attempt to get him to tell them where his family was hiding, but Daniele insisted that he had no contact with them. If they had learned about his correspondence with Anna, all of them — and the people who were helping them — would have been in grave danger.

To ensure that they were not discovered, Daniele burned Anna’s letters immediately after reading them. He even warned Anna to only use paper that burned quietly, for fear the guards might hear the crackling and investigate.

‘I will be lucky if I return to you all’

Daniele wrote to his wife and sons about his experiences at the prison, about the people being “sent away to work,” and about his love for his family and his memories of them. He was especially haunted by the memory of a time when his sons came home crying because some other children had called them “Jewish pigs” and beaten them up. At the time, Daniele was angry and punished his sons for failing to defend themselves. Years later, sitting in a prison cell for the “crime” of being born Jewish, Daniele deeply regretted the way he had handled the situation, and wrote to his sons more than once to ask their forgiveness for the incident.

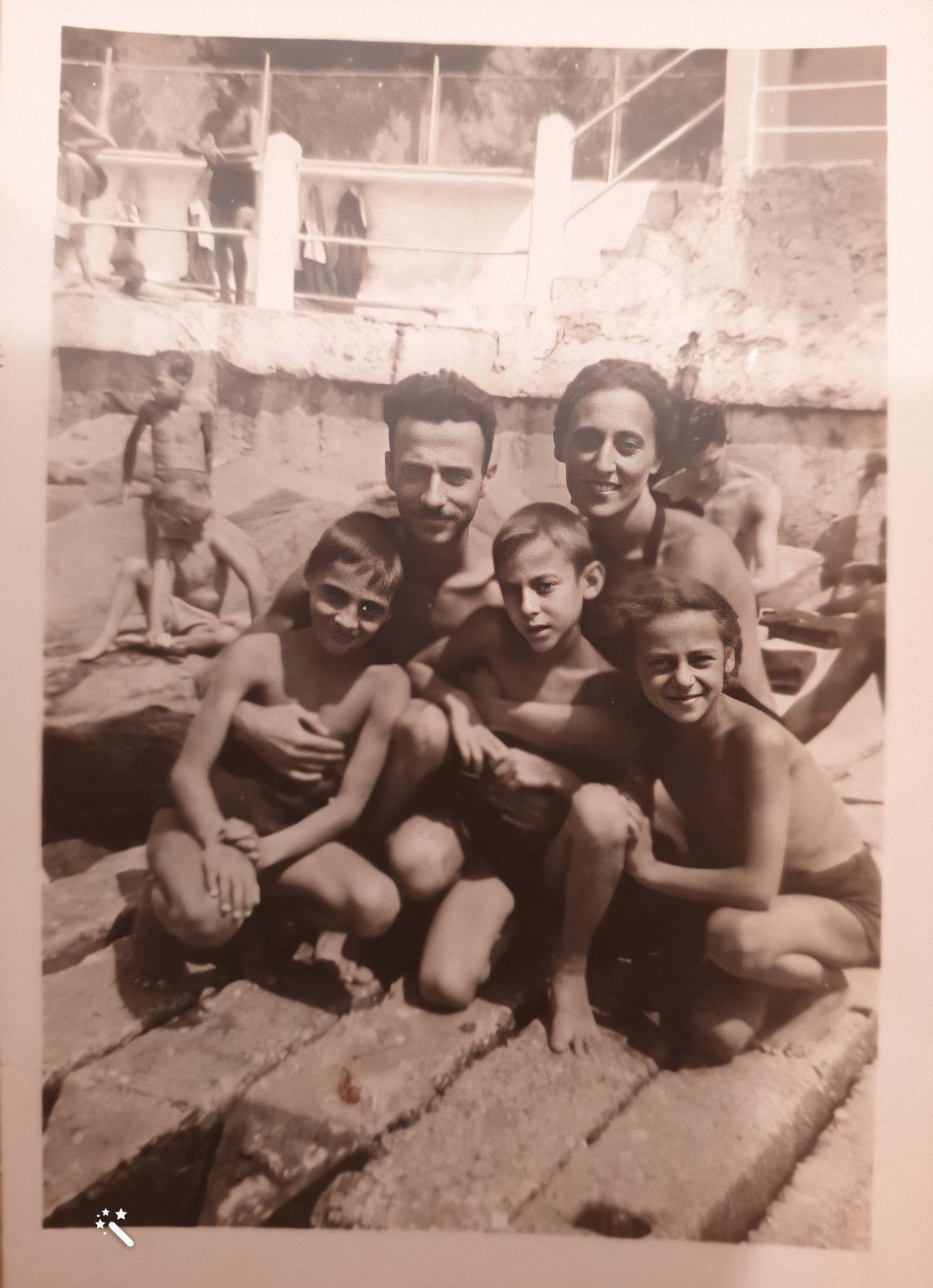

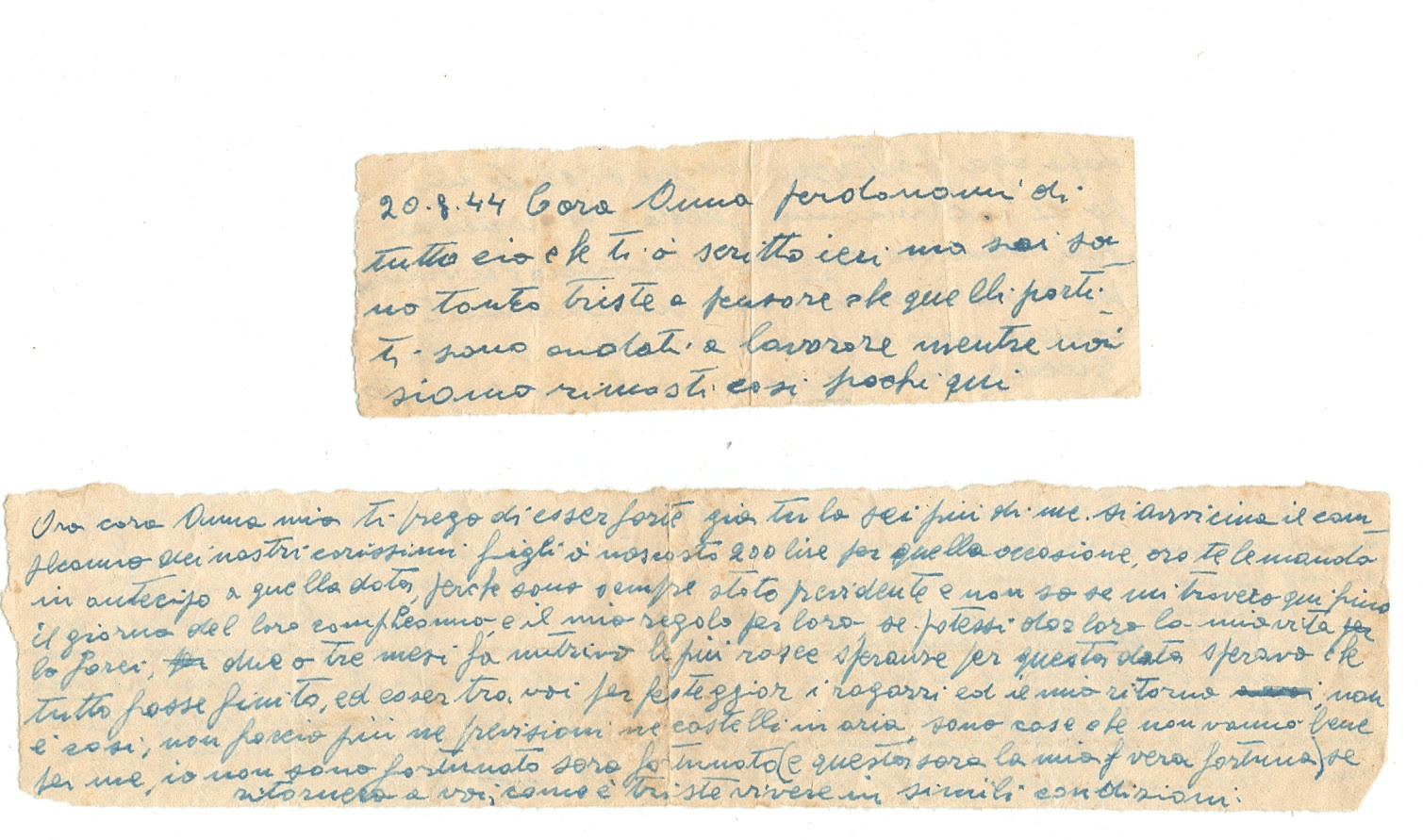

Below is a translation of a letter Daniele sent on August 20, 1944:

Dear Anna,

Forgive me for everything. I wrote to you yesterday, but, you know, I’m so sad. To think that those who left went off to work, while so few of us are staying here. After every departure, we always feel a little melancholy. More people left this time than in any previous departure, and, you know, to think that they left to go to work while we’re staying in jail, you can’t be pleased. If only it were possible that the war would end soon, but who can tell?

Now, dear Anna, I ask you to be strong. You are stronger than me already. The birthday of our dear boys is coming soon. I hid 200 lire for this occasion. Now I’m sending you the money in advance because I have always been the provider, and I don’t know if I’ll still be here in jail for their birthday. This is my present to them. If I could give them my life, I would. Two or three months ago I had hopes for this day. I hoped that everything would be over, and to be with you all to celebrate the boys and my return. But it’s not this way. I don’t make predictions anymore, or castles in the air. It’s not good for me. I am not lucky. I will be lucky (and this will be my true luck) if I return to you all. How sad it is to live in such conditions.

Dear Anne, tell my dear boys that I send them my best wishes. These are the wishes of a father who loves them very much. I’m sure they will remember me. This thought will comfort me a little. Your thinking of me will complete the rest of my life. How many sad things I have to write on occasions that should be so joyous instead. Lucky are those who resign themselves to fate. If God thinks me worthy, I give my blessing to the boys and you hoping for His [God’s] blessing. I wish the boys a happy and healthy life, and, to you Anna, the hope that God will fulfill your prayers. Regards to all, thank those who help you and helped me as well. Kiss the dear boys for me. A big and warm kiss to you.

Yours,

Daniele

As time went on, it became clearer to Daniele that those people being “sent to work” were being sent somewhere much more sinister, and that his turn would soon come. 4 months after he wrote the above letter, on September 2, 1944, he was put on a train to Auschwitz — but even that didn’t stop him from writing to his family.

When he was already within sight of the death camp, he wrote one final letter that he managed to send to Anna through a worker on the train he knew. “From the distance you can see the smoke,” he wrote. “There’s so much smoke here. This is hell.”

That was the last his family ever heard from him.

The deaths of Dario and Vittorio’s grandparents were documented at Auschwitz, but their father’s wasn’t. They heard that he’d been seen alive two weeks before the camp was liberated, and Anna searched for him for years, to no avail. Dario and Vittorio believe their father was probably moved towards a camp further west, away from the advancing Allies, in a death march — and likely perished along the way.

Rediscovering the letters

Anna, Dario, and Vittorio returned to their house in Trieste after the war, but immigrated to Israel in 1949 — in fulfillment of a wish expressed by Daniele in one of his letters. Anna kept the letters safe in a drawer in her Tel Aviv apartment, but the family very rarely spoke about the events of the war. After Anna died at the ripe old age of 96, her sons were cleaning out her apartment and discovered the letters.

Then, years later, they were contacted by the MyHeritage Research team. Many of the Jews of Corfu, an island in Greece, had moved to Trieste — including some of Anna’s family members — and the researchers at MyHeritage got in touch with Dario and Vittorio in that context. When Vittorio casually pulled out the collection of letters his mother had preserved, MyHeritage researcher Roi Mandel couldn’t believe his eyes. With the permission of the family, Roi photographed the letters and assigned a member of his team — Elisabeth Zetland — to transcribe and translate them.

Elisabeth spent months transcribing and translating the letters. When the project was done, MyHeritage presented copies and translations to the family, while the originals were donated to the Yad Vashem archive in Jerusalem.

Since Daniele wrote an average of a letter per day, Elisabeth found herself reliving the experience with him as she read, transcribed, and translated. She describes the emotional process Daniele goes through, reminiscent of the process many other Jews were experiencing at the time: from confusion, thinking there must have been a mistake, to boredom, frustration, heartache, and seesawing between hope and despair. Elisabeth believes writing to his wife and sons helped him cope with the unbearable circumstances.

It seems clear from the letters that he became gradually more aware that he would never see them again, and he took the opportunity to impart important life lessons to his sons about how to be good men.

“Be good and true brothers, love each other always. That way you’ll make me and your dear mother, who is such a good person, happy.”

His sons have internalized and lived that message. Dario and Vittorio went on to establish families of their own — each of them naming a son Daniel after their father — and now have 13 grandchildren between them.

“The two of us are always in touch, every single day,” says Vittorio.

A powerful legacy

Daniele Israel’s letters have left a powerful legacy for his children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren: a glimpse into his experience during this terrible period, and an extensive tribute to his devotion to his wife and children. We at MyHeritage are honored to have had a part in preserving these priceless documents and making his message of love and hope accessible for future generations.

Child of God

August 6, 2020

I could not read it all but b is very interesting thank you