My local shop will comment if I am not wearing a mask that d

As people around the world begin to emerge from sheltering in place, they find themselves in a strange new reality: one where half of our faces are hidden. Though they are here to protect us, the presence of masks can pose some new challenges — and the way we choose to cope with those challenges is just one expression of how we adapt to our new post-lockdown world.

But the difficulties surrounding the use of masks goes back much farther than 2020. The MyHeritage Research team took a look at our newspaper collections to examine the surprisingly similar attitudes towards masks during previous epidemics in history.

In this post, we’ll explore the social and psychological factors that influence our attitude towards masks, both in the present day and during previous pandemics.

Living in a masked new world

How do we communicate with half our faces covered? Can we still express emotions? We are certainly not alone in this confusion.

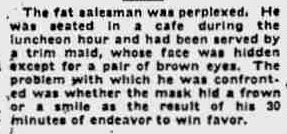

Back in 1918, at the height of the Spanish flu, the Daily Californian described a man seated in a cafe during the luncheon hour, trying his best to converse with a waitress whose face was hidden except for a pair of brown eyes. The problem with which he was confronted was whether the mask hid a frown or a smile.

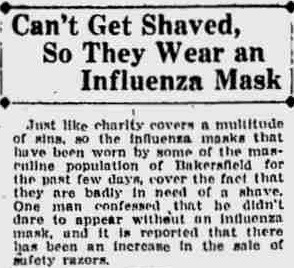

Though very much a struggle to get used to these new communication barriers, some have tried to find the perks in this new reality! In the very same article found in California Newspapers, 1847–2009, some see the mask as a way to hide their lack of grooming.

“Just like charity covers a multitude of sins,” it begins with a wink, “so the influenza masks that have been worn by some of the masculine population of Bakersfield for the past few days, cover the fact that they are badly in need of a shave. One man confessed that he didn’t dare appear without an influenza mask, and it is reported that there has been an increase in the sale of safety razors.”

Masks take on a new form of self-expression

With parts of our physical selves hidden, wearing certain types of masks can be a form of expression in their own right. Are you sporting a disposable surgical mask? An N95? A DIY mask? Does your mask match your outfit? Masks are now the first thing we notice in each other and have become part of our human landscape.

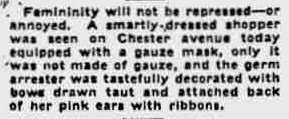

In the same article from The Daily Californian, we see that this was not lost on some women in 1918.

“A smartly-dressed shopper was seen on Chester avenue today equipped with a gauze mask, only it was not made of gauze, and the germ arrester was tastefully decorated with bows drawn taut and attached back of her pink ears with ribbons.”

Finding a means of self-expression in masks and customizing masks with personal at-home touches may be a way we can adjust to our new “look.”

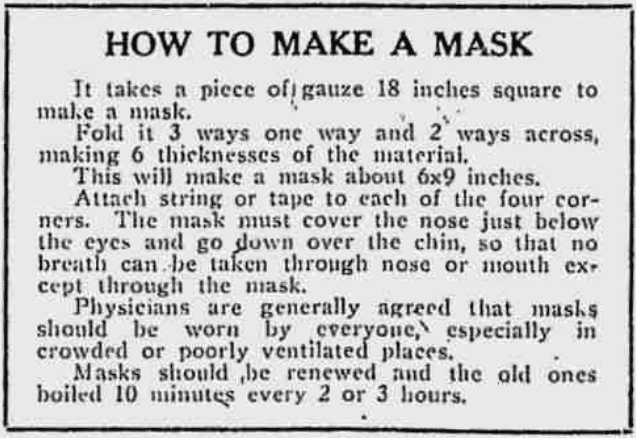

Back in 1918, another newspaper in California Newspapers, 1847–2009, ran this useful item on October 24, 1918:

The article gives instructions for creating a homemade mask out of an 18-inch square piece of gauze. “Fold it 3 ways one way and 2 ways across, making 6 thicknesses of the material,” it instructs. “Attach string or tape to each of the four corners. The mask must cover the nose just below the eyes and go down over the chin, so that no breath can be taken through nose or mouth except through the mask.”

Whether professionally manufactured or sewn at home, customized masks offer people the chance to cover their faces with great style and personality in lieu of the standard surgical mask. This has turned the mask from an irksome burden into a newly sought-after fashion item.

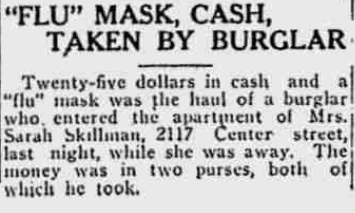

It seems that in 1918 masks were also perceived as items of value, because this burglar in Berkeley apparently thought a flu mask was worth stealing:

“‘Flu’ mask, cash, taken by burglar,” reads the headline from the Berkeley Daily Gazette on November 14, 1918. “Twenty-five dollars in cash and a ‘flu’ mask was the haul of a burglar who entered the apartment of Mrs. Sarah Skillman, 2117 Center street, last night, while she was away.”

Making masks mandatory

With the first wave of COVID-19 winding down, many places are reopening on the condition that masks and social distancing laws are enforced to prevent a second wave. Many countries have started instituting fines to enforce these rules.

During the Spanish flu pandemic, there was still very little known about the science of germs and illness, but even then local authorities knew that masks helped prevent the spread of flu symptoms and strongly enforced their use.

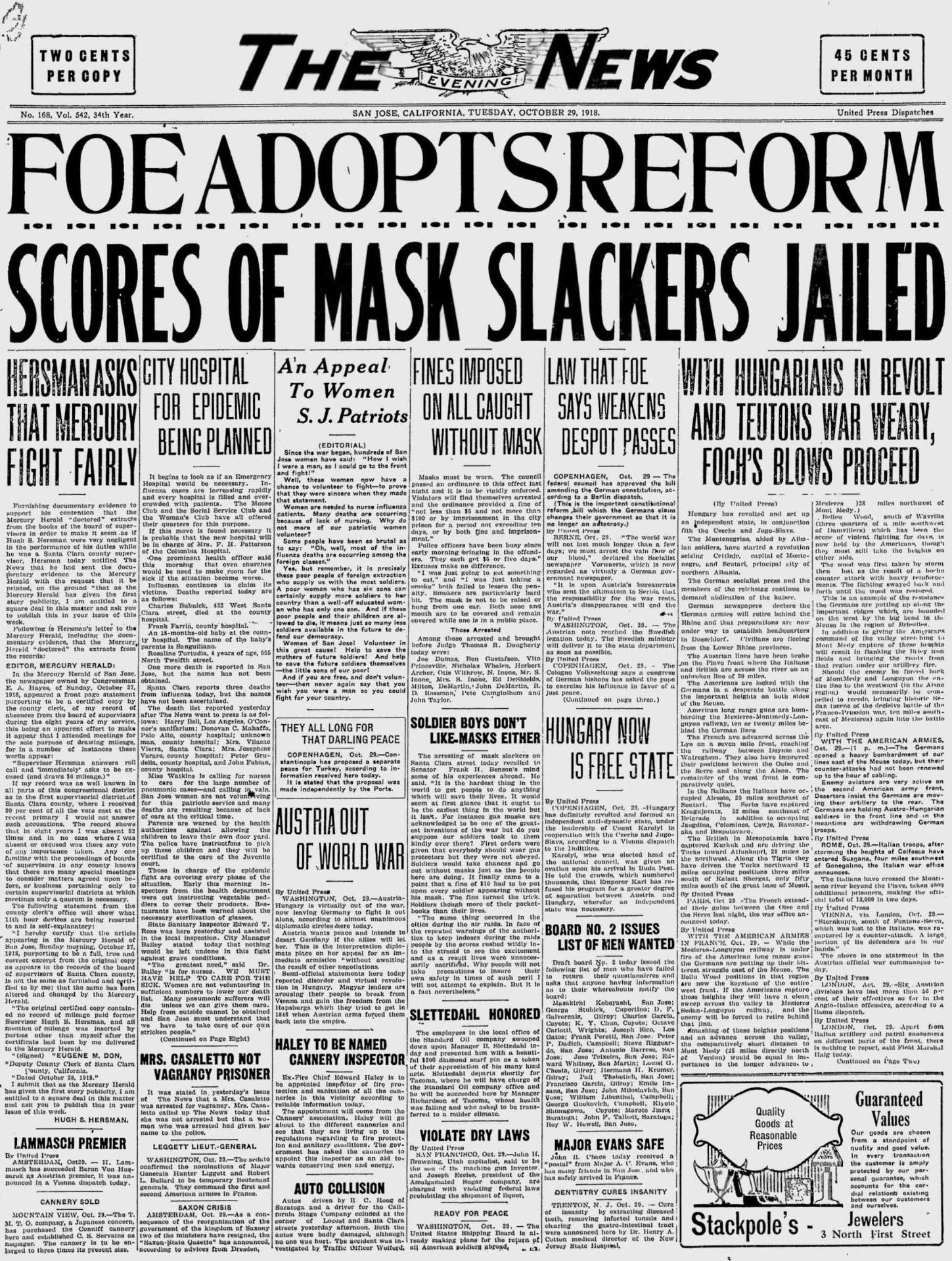

In California, residents faced fines and jail time for being in public without a mask. “Scores of mask slackers jailed,” screams a headline from The Evening News on October 29, 1918.

In 2020, countries have also leveled fines against people who aren’t wearing masks in public places but as of yet no jail time.

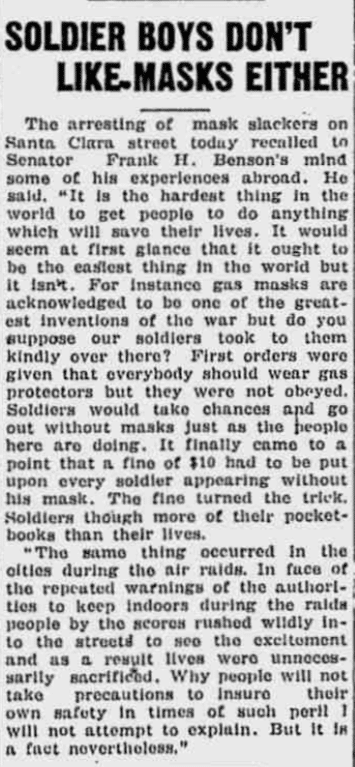

Why did they institute such harsh measures to get people to wear their masks? It appears that protecting one’s health is just not enough of an incentive. In one of the articles on the front page above, Senator Frank H. Benson recalled that even getting soldiers to wear protective masks against deadly poison gas was shockingly hard to do.

“It is the hardest thing in the world to get people to do anything which will save their lives,” he told The Evening News. “First orders were given that everybody should wear gas protectors but they were not obeyed. Soldiers would take chances and go out without masks just as the people here are doing. It finally came to a point that a fine of $10 had to be put upon every soldier appearing without his mask. The fine turned the trick. Soldiers thought more of their pocketbooks than their lives… Why people will not take precautions to insure their own safety in times of such peril I will not attempt to explain. But it is a fact nevertheless.”

Why, indeed? We don’t have answers either, but it’s clear that there are several factors at play. Some of these may be related to what we mentioned earlier: difficulty communicating and interpreting one another’s expressions, dealing with a physical barrier, adjusting our self-image, and so on. Another factor that contributes to a reluctance to wear a mask may be peer pressure.

Mask peer pressure

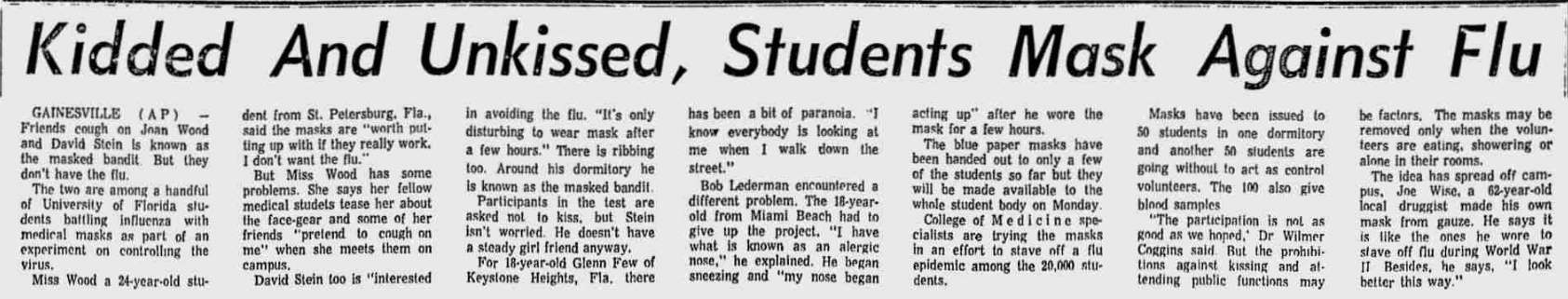

During a flu pandemic in 1969, the University of Florida ran an experiment to see if masks were effective at stopping the spread of the virus, and the students who volunteered faced more than a few social challenges.

The above article found in Florida Newspapers, 1901–2009, describes the experiences of a few of these students. One said she was teased by her fellow students, and some of them pretended to cough on her. Another reported feeling very self-conscious: “I know everybody is looking at me when I walk down the street.”

Anyone who has walked down a street wearing a mask in an area where wearing masks are not common practice will feel for these students.

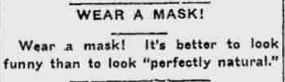

Another clip from California Newspapers, 1847–2009, highlights the issue of a “funny” appearance:

“It’s better to look funny than to look ‘perfectly natural,” it says. It seems we aren’t the only ones concerned about what others think of us.

Making sense of these “masked” times

In many ways, the mask you choose to wear has become a visible symbol of how we cope and interpret our new COVID reality. Whatever way we view it, knowing that we are not alone in this situation — but rather walking on the well-trodden paths of our ancestors — can provide us with some comfort as we try to make sense of these difficult times.

Ultimately, if we come together as a human family and wear the masks despite the challenges, one day we’ll look back at the newspapers of today and be proud of what we did to protect each other.

In the meantime, you can search our newspaper collections to discover the stories of your own ancestors.

Lars Nelson

July 26, 2020

I wished MyHeritage would offer longer periods of genealogy research as I’m not on Facebook everyday and when I do I’ve missed out on another chance to take advantage of.