Swedish Surnames: A Guide to Understanding the Origins of Your Swedish Roots

- By Talya

Foreign language obstacles and patronymic naming patterns are commonly cited reasons for avoiding Swedish genealogy research. But with an understanding of a few basic concepts, Swedish genealogy research can be simple, fun, and successful! In this post, you’ll learn more about the origins of Swedish surnames and get hints and tips for finding out more about your Swedish name online. You can start now by searching the millions of Swedish clerical records in the Sweden Household Examination Books, 1860–1947.

What is a patronymic name?

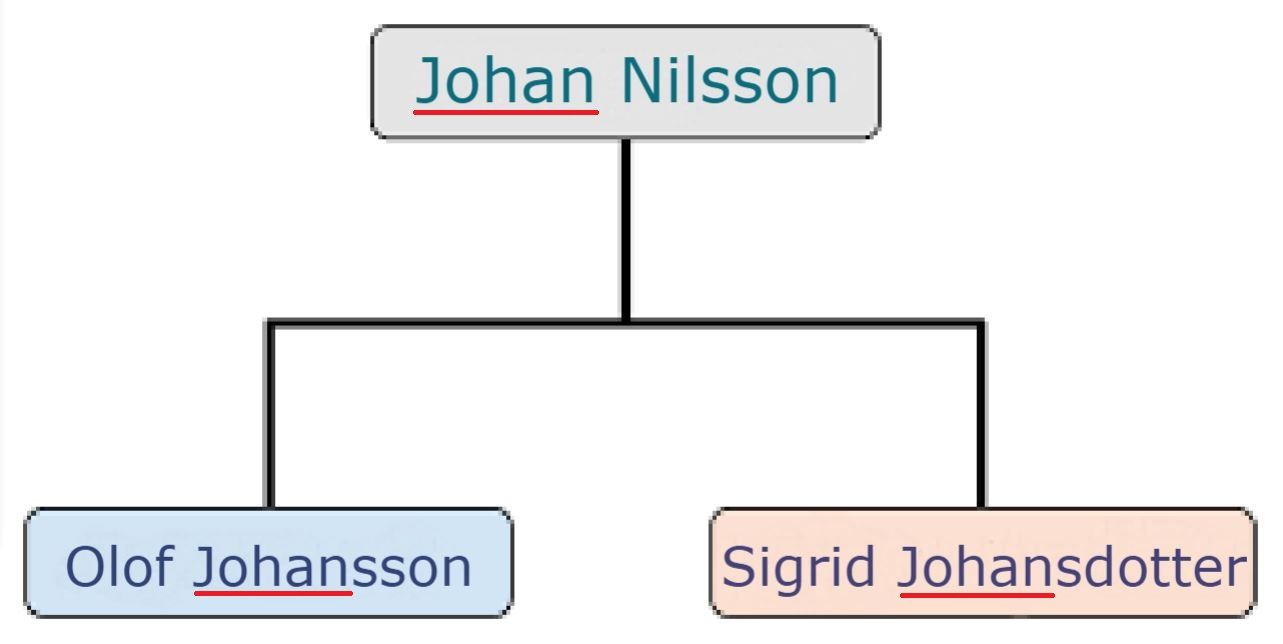

A patronymic name is one that is created when a prefix or suffix is attached to the father’s name. For example, the patronymic surname Johansson can be broken into two parts: Johans’ son. This means that someone with the surname Johansson was the son of Johan. Likewise, a surname of Johansdotter is the patronymic version used for the daughter of someone named Johan. Because of this patronymic naming pattern, a brother and sister may have had similar, but not identical, surnames from one another.

In a patronymic naming pattern, a son and daughter’s last name will be based on their father’s first name but will differ to reflect their gender.

While it is common in many English-speaking countries to adopt a surname and pass it down for many generations, this was not the case in Nordic countries. It was common for the patronymic surname to change with every generation. Another interesting note that pertains to Swedish surnames is that women did not take their husband’s surname, but rather, maintained their maiden patronymic surname.

Non-patronymic surnames

While patronymic surnames were common, some surnames were established based on other identifying characteristics, such as a physical attributes, occupation, or location where the individual lived or worked. This practice was commonly used by soldiers as a means of differentiating between other soldiers with the same patronymic surname. After their military service ended, many soldiers opted to drop these assigned surnames, but some opted to use the surname throughout their life.

Modern Swedish surnames

In the mid to late 19th century, the patronymic naming system began to fade. The -dotter suffix was replaced with women adapting the -son suffix. It became more common for a surname to be passed on over multiple generations, and women more frequently adopted their husband’s surname. Oftentimes as Swedes migrated to other countries, they would modify their surname to more closely resemble the language of the new country.

Diving into Swedish records—even if you don’t speak Swedish

Understanding how Swedish surnames have evolved over the years will help as you dive into Swedish historical records. Particularly in late 18th and 19th century records, record formats are tabular and an in-depth knowledge of the language is not required to make exciting discoveries. Additionally, different types of church records regularly reference one another, enabling researchers to trace their Swedish ancestors for every year of their life from birth to death. Even when an ancestor’s record trail turns cold, recent publications and indexes created by active Swedish genealogical societies make it possible to pick up the trails of elusive ancestors in earlier and later records. Not only do common Swedish records provide material for drawing genealogical connections, but the level of detail in these records also provides ample material for the construction of biographical narratives — even if you don’t speak Swedish.

Swedish Church Records

Swedish church records are one of the most utilized sources for Swedish genealogy. In addition to birth and christening (födelse och dop), marriage and engagement (vigsel och lysning), and death and burial (död och begravning) records, Swedish church records also include moving-in lists (inflyttade), moving-out lists (utflyttade) and a unique record known as the “husförhörslängd” — the clerical examination. You can search over 100 million clerical records in the MyHeritage collection, Sweden Household Examination Books, 1860–1947.

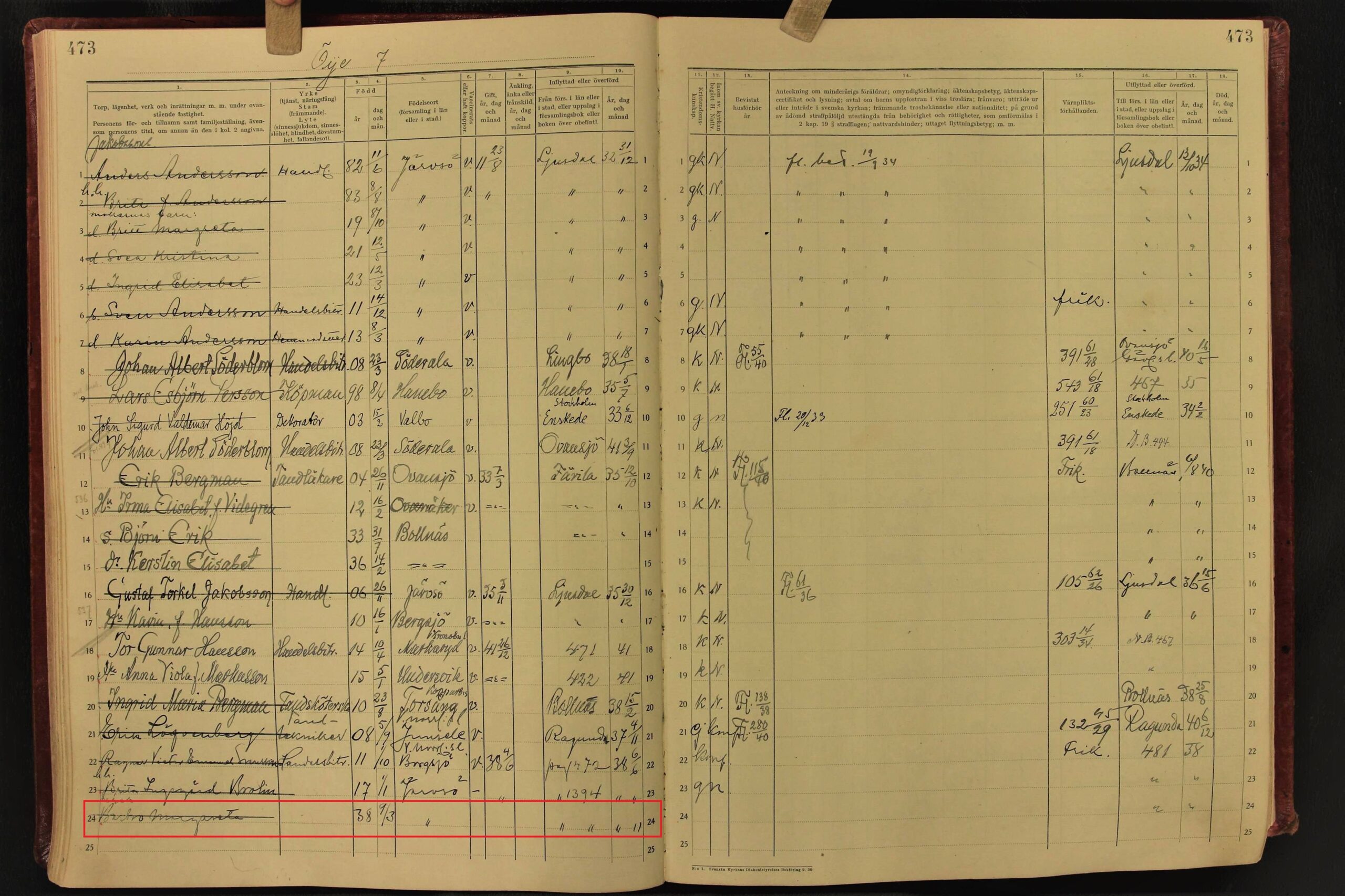

Household examination (husförhörslängd) listing the beloved Swedish singer and actress Barbro Margareta Svensson more known as “Lill-Babs”

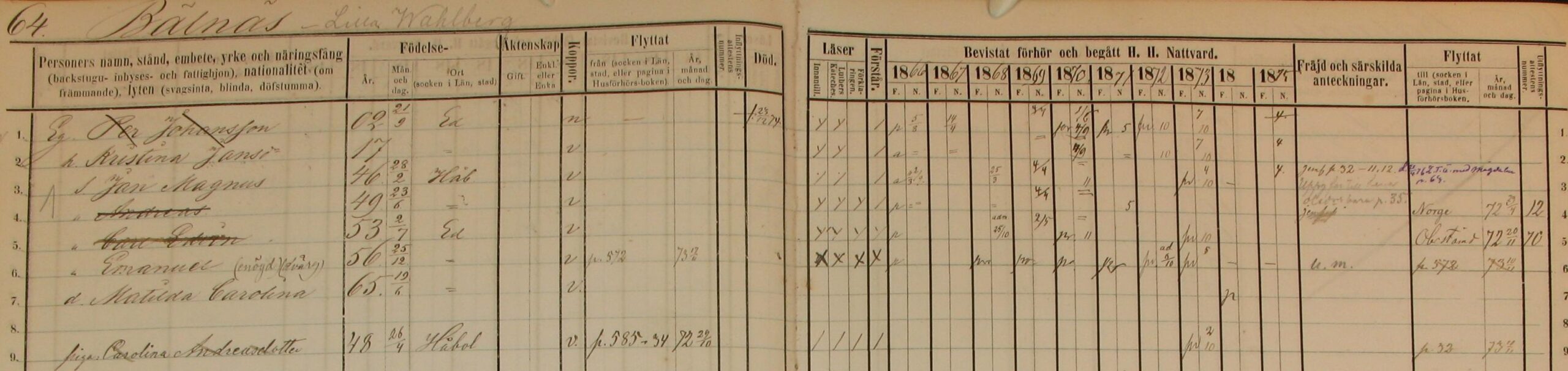

Swedish church records in the 18th and 19th centuries were often maintained in tables and were largely composed of names, dates, and residences. Dates were frequently recorded in number formats according to the European system (dd-mm-yyyy). As a result, anyone interested in conducting Swedish genealogical research can learn a great deal from Swedish documents with little knowledge of the Swedish language. For the few words you may need to learn, consider reviewing this list of words commonly found in Swedish documents available through FamilySearch.org. Longer annotations can be deciphered and interpreted through free tools such as Google Translate.

As mentioned before, Swedish church records frequently reference one another. In particular, the clerical examination or “husförhörslängd” can act as an index of important family events. Beginning in 1686, each parish was required to keep such records for each household. Early records may have been discarded, but eventually statistical tabulations and tax rolls required the preservation of these documents. Copies of these records exist for many parishes in Sweden after about 1780. As part of the household examination, parish priests of the Swedish Lutheran Church were required to visit with the members of their parish at least once yearly and test them on their knowledge of the catechism. The ledgers they utilized were reused over the course of several years and not only include information about the family’s religious duties, but also include additional information regarding migration, family structure, residence, and important family events.

Discovering details about Swedish ancestors

Typically, these registers will include information for a family over the course of 5–10 years. If a child was born, they were added to the clerical examination and their birthdate and christening date was noted. If an individual or a family moved within the parish, a note was made in the clerical examination and a reference to the page number of the family’s new residence was also made. If they moved outside of the parish, the date they left was often recorded, along with the number of their listing in the moving-out books. The dates of deaths, confirmations, marriages, vaccinations, and communions were also recorded. If you’re lucky, additional notes might comment on crimes, physical characteristics, occupations, punishments, social standing, economic status, or other life events with references to pertinent records.

The above record is from the Dals-Ed Parish in Älvsborg covers the years from 1866–1875 and shows the household of Per Johansson on the farm of Lilla Wahlberg in Bälnäs. The document provides birthdates and birthplaces for each household member. It shows that Per’s son, Andreas, moved to Norway in 1872. Another son, Emanuel, moved within the parish but returned after just a month. Among other notes on the document, we learn that Emanuel only had one eye and that he was a dwarf.

Not only do household examination records reference other church records, but birth, marriage, death, and migration records frequently reference household examination records. Birth records might list the page number of the child’s family in the household examination. Marriage records will indicate the corresponding pages of the residences of the bride and the groom. Death records identify the residence of the deceased. Moving-in and moving-out records will frequently report the corresponding page numbers of the farm where a migrant eventually settled or the parish from which he came. Even if these records do not list the specific pages of interest, they may still provide the reported residences which can then be located in the clerical examination records.

Most clerical examination volumes include an index of farms and residences within the parish. In the case of some larger parishes and cities, local genealogical societies have sometimes indexed all individuals in the volume by name. When researching in multiple volumes, note the farm or residence of your ancestor in the previous record and then search the index of residences near the front or end of the next clerical examination volume. Usually this will narrow your search to just a few pages out of the book rather than the entire volume.

Strategies for overcoming brick walls in Swedish genealogy research

Occasionally an ancestor might have moved during a year for which migration records are not currently available, or they might have moved to a larger city with many parishes. Other times their migration may not have been noted, or jurisdiction lines may have been redrawn, resulting in the formation of a new farm and residence. In these cases it may be difficult to continue tracing an ancestor’s record trail. One strategy to overcome these situations is to search the clerical examinations by reported birthdate. The birthdates or ages of Swedish ancestors are recorded in many of their records. If you are browsing through large collections, consider searching by birthdate rather than by name. Since birthdates were often recorded in their own unique column and are more immediately recognizable than names, this may expedite your search. If these strategies still yield no results, searches in indexes may help to uncover an elusive ancestor’s record trail.

Online resources for Swedish genealogy research

In recent years, online indexes and databases have made Swedish genealogy research simpler than ever. MyHeritage has a large collection of vital records from Sweden, including birth, marriage, and death records. Additionally, MyHeritage has partnered with ArkivDigital to index the Sweden Household Examination Books, 1860–1947. If the record trail of your ancestor or another relative runs cold, you might pick it up again by searching some of these indexes for records before their earliest known record, or after their last known record. Often, by consulting the corresponding church records mentioned in the indexes, it is possible to close the gap in their record trail. Given the resources available for Swedish genealogy research, success is imminent. Don’t let language or patronymics frighten you away from the amazing genealogical discoveries waiting to be uncovered.

If you have Swedish ancestry and would like help tracing your lineage, the experts at Legacy Tree Genealogists can help! Legacy Tree Genealogists is the world’s highest client-rated genealogy research firm, and recommended research partner of MyHeritage. Founded in 2004, the company provides full-service genealogical research for clients worldwide, helping them discover their roots and personal history through records, narratives, and DNA. For more information on Legacy Tree and their services, visit: www.legacytree.com.

chris svanberg

May 7, 2021

Using patronyms for genalogi after circa 1900 is 99.99999% a waste of time. As the gamut of male names was quite small, not much of genetic relationships can be made from the -son and -daugher names. They could pretty much be ignored as they do lead to some really stupid results.

So how do you track people in Sweden thru the church records? (Some bigger cities had their own system based on tax rolls.)

If you read this in you likely have no idea, and you may be a descendant from a Scandinavian.

Lets say you have their name, then you need D.O.B, and immigration record or date. The shipping manifest may have country of origin and names of passengers in their company. If Sweden, there is a database called Emihamn where you can search for the names, date of departure along with Age, so D.O.B may have to be calculated. If they went by a stop in Liverpool or elsewhere, there could be some time delays in US immigration records that have to be considered.

From Emihamn you could find the Parish of origin, where you can look in their database for Parish moving records. In those all movement of people were recorded.

This record will tell you what farmstead, or house name they came from. Addresses did not exist back then as we know today.

The Household Examination, or Husforhors, records will most often have a list of house or homestead names, with a page reference. This page number will lead to a complete record of people for that location, past and present, servants, live-ins and all, for the noted time period of the book. People who have moved out will have a line thru their names. Relationships are noted too, along with origin parish, date of birth, marriage date, date of moving in and the like. Smallpox vaccination may have its own column, and also reading and writing ability, and other goodies. The earliest records were more focused on church doctrine knowledge, and less so on later books, and can be very sparse on civil details.

Very early handwriting can be difficult to decipher, books and YouTube videos can be found on the topic.

With a date of birth and parish you will find the names of parents and their homestead name, from which you can jump to the Household Examination index and find their residence as above.

Patronyms ruled, but non-patronyms existed too, mostly for soldiers who got their names assigned to them from their regiment. Some kept them some did not. Name laws were quite relaxed. You will never see a married woman having a surname change.

I have never seen it. In the records they kept their original “surname” or partronym.

People in towns and cities often changed their names to something durable, and unique as the population density would make patronyms impractical based on the small catalog of male names.

Men entering professions may often adopt a non-patronymic name, common among iron and steel workers. German and Belgian immigrants usually stuck with our conventional format, and later generation incorporated the patronym in addition to the durable family name.

In some areas, the name of the farm was added in front of the “first name”.

In short thread carefully with “last names” in old times, do not presume current naming conventions applied back then.

I wish MyHeritage would be more open to adding a data field between “first” and “last” name for Partonym, just as now Prefix and Suffix are optional. Now if a person has both a durable family name AND a patronym, I add the patronym to the “first” name data field, as to avoid Myheritage’s clumsy presumptions. Another presumption is if a person is alive, if more than 120 years it would be safe to assume the person is dead, unless she made it to the Guinness Book of World records, or the family tree stretches back to Metuselah.