Thank you for sharing this journey Debbie!

African American Genealogy Research: Four important elements

- By Schelly

In honor of Black History Month, Carolyn Tolman of our recommended research partner, Legacy Tree Genealogists, has written this guest post on African American research.

Many of us face challenges when conducting African American genealogy research. We begin with relatives closest to us, or known information about subject families, and follow trails that hopefully lead to the 19th century and beyond.

The 1870 population census is a great source, as it enumerated, for the first time by name, many African Americans. The 1870 census may also present discrepancies or conflicts with historical family data. Given names and/or surnames, and specific locations may differ from our family data. Conflicts can divert us from our established path as we know it, forcing us to rethink our strategy.

Our currently-held information can provide opportunities to expand our search, if we carefully analyze our findings.

So, how do we research ancestors for whom we may not have accurate surnames and locations? Where do we focus our search, once our “facts” are overturned with conflicting information? What do the details tell us? Have we retrieved information that conflicts with existing evidence? Do we possess written sources to support oral family stories? When we face inevitable obstacles to our research, we must step back and analyze our retrieved records.

We must utilize creative research practices to assist in searching for, retrieving and analyzing sources, to provide a body of direct and indirect evidence to support our research. Consider these four elements to enhance your research.

1-Be objective in your analysis

“Think outside the box.” Don’t accept secondhand information as absolute fact, but pursue all viable, relevant possibilities. Consider variations of given names, surnames and other data found in records created by a third party such as census enumerations. If your ancestor was enslaved, be mindful that their chosen surname may not match that of a probable slaveholder. Remember, the history and documentation of African American lives has not been straightforward; therefore, we must be creative when accessing and analyzing available records.

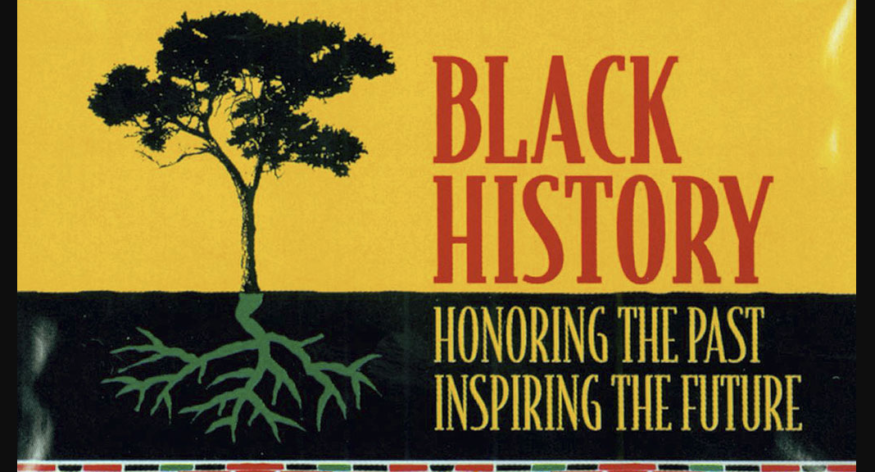

The following image shows a deed of emancipation filed in 1850, by John Morford to emancipate his slave, Octavius Alexander. Imagine the confusion to a descendant who may have heard John Morford was the slaveholder of an ancestor, but nothing about a different surname for the enslaved individual.

1850 Mason County, Kentucky County Court, May Term, Order Book. Mason County, Kentucky, Court Order Books, 1850 May Term, p. 427, Deed of Emancipation, John Morford emancipates enslaved Octavius Alexander, “County Court Order Books of Mason County, Kentucky 1789-1870,” digital images, Familysearch.org, https://familysearch.org.

2-Diversify

Diversify your search efforts to incorporate county court, tax assessment, slave schedules, probate, property, city directory and military records. Analyze census and vital records you have retrieved to establish a summary profile for respective ancestors. Determine which historical record groups may provide additional evidence. It is important to venture beyond census schedules and vital records in our quest to validate family relationships.

3-Expand your research

Expand research to neighbors in census enumerations, associates noted in court records and tax records, and known and suspected extended family members. “Widen the net” to search for information that may indirectly lead to evidence about our ancestors’ lives. This is called cluster research, researching groups of people, rather than one or two direct family lines.

When researching a formerly enslaved family, cluster research must include the lives of potential slaveholders. Enslaved individuals are not listed by name in the census until after Emancipation; however, slaveholders appear in slave schedules, various court records, and estate documents that may identify enslaved individuals by name. Slave schedules identify the enslaved by approximate age, color and gender, but not by name. However, this information is valuable to establish possible matches when analyzing our total body of evidence.

4-Indirect evidence

This type of evidence is vital to proving relationships and answering research questions. This evidence may not directly answer a specific research question but, combined with other indirect evidence findings, we are able to “build a case” for relationships. Understand the significance of relevant indirect evidence in all retrieved sources.

A recent client case illustrates many of these principles. Identifying the owner is the first step in researching an enslaved person before Emancipation. In 1870, the neighbor of a former slave Simon Cooper [names have been changed] and his children was John Cooper, a white man. While Simon Cooper held no real estate and $400 of personal property, his neighbor, John Cooper, owned $2,500 of real estate and $1,200 of personal property.

Only one Cooper family owned slaves in White County, Tennessee on the 1860 slave schedule, enslaving a two females, ages 45 and 12; neither swas the right age or gender to be Simon Cooper. Research efforts shifted to the county probate records and led to a breakthrough. In 1834 John Cooper, Sr. willed his “negro boy named Simon” to his wife, Rebecca.

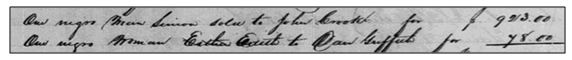

In the 1840 census, John’s widow Rebecca was listed with one male slave, aged 24-35 and one female slave, aged 55-99. After an inventory and account of Rebecca Cooper’s estate in 1841, the Circuit Court ordered her administrators to sell her slaves to satisfy her debts. Rebecca’s son, John, Jr., purchased “One negro man named Simon … for $923.00.”

Probate Court Books, Settlements and Wills, 1831-1841, White County, Tennessee, page 75, http://familysearch.org, accessed July 2017

Then, in 1850, John Cooper, Jr. owned one slave in the 1850 slave schedule, a black man, aged 41. Simon stayed with John Cooper for 1860 when John, Jr., moved to another Tennessee county, where Simon was listed in the 1860 slave schedule. This move was traced through property records, and the identities of the slaves would be unrecognizable if not for earlier probate records and the 1870 census. The implied family consisted of Simon, an unnamed mother, a daughter, 19, and the three children named in the 1870 census. The ages were slightly different, but it appeared that the unnamed mother had died and the three children lived with their father. The family relationship was further established when Simon’s daughter moved to Alabama, where other White County community members were also living.

This case was a classic example of tracing enslaved persons through slave schedules, probate, and property records. Simon matched his owner’s surname because he stayed with the same slaveholder and his son for much of his life. Simon’s surname might have been different if he had been sold or willed to a son-in-law or if he would have selected a different surname. Tracing the former owners was essential to tracing the family of the enslaved person.

The family was found by widening the net to include the slaveholder and his extended family, examining property records of the slaveholder’s children, probate records, the slave schedule, and the regular census. Additional clues came from the birth and death records of the former slaves’ children and grandchildren. Searching broadly and widely connected the family from Alabama back to the former slaveholder in Tennessee.

African American genealogy research can be challenging, but overcoming those challenges with patience and persistence can be very rewarding.

Legacy Tree Genealogists is the world’s highest client-rated genealogy research firm, and recommended research partner of MyHeritage. Founded in 2004, the company provides full-service genealogical research for clients worldwide, helping them discover their roots and personal history through records, narratives, and DNA. Visit Legacy Tree Genealogists for more information.

Debbie Campbell

February 16, 2018

I was surprised to find an African / American Slave Ancestor, I wondered why in nearly every generation, of my Paternal line led me back to another Imanuel first name? Our relatives now have Lupus, which could be hereditary. Our Ancestors had a first son in America and a second son in Scotland, as Emanuel Fisher fought against Slavery twice, in two USA, Army Regiments. His second son also Imanuel was the only boy born in Scotland UK in 1874. with these names.I have traced this family back to 1790 approx in America/Pennsylvania then Great Britain, wonderful history but awful at times.Thanks to My Heritage , we found this information !!!!