This post was written by Laurence Harris, Head of Genealogy UK at MyHeritage.

This post was written by Laurence Harris, Head of Genealogy UK at MyHeritage.

It is important to record key events of our ancestors, including the date when each event occurred.

Usually several sources indicate an event’s date. For example, for a death: the date may be indicated on a death certificate, a headstone, a newspaper obituary and in a Grant of Probate (which authorizes distribution of a deceased person’s estate). However, those dates would have been documented using the calendar and recording conventions of the geographical location and time when the event originally took place, rather than the calendar and conventions with which today’s researcher would be familiar. Failure to take into account the original context of an event or document often results in mistakes in understanding when an event actually happened.

Here are five of the most common mistakes that can occur in interpreting dates, together with suggestions as to how these mistakes can be avoided or corrected.

1. Mixing up American and English date formats

“Elizabeth Green was born on 12.11.1904.” Family historians in the US are likely to interpret this date as December 11, 1904. However those in the UK are likely to interpret this date as 12 November 1904. Only one is correct! The original record and where any subsequent transcription took place will help to determine if this was a December or November birth. Look for nearby transcriptions in the same document to see how other dates are recorded. If you spot another date recorded as 7.13.1925 then the 13 must be a day number (as month number 13 does not exist) so the American convention of mm.dd.yyyy had been used. Therefore, Elizabeth Green was born December 11, 1904. However, if you see another date like 13.7.1925 then you can assume that the first number is the day, and that Elizabeth was born on 13 November 1904.

To avoid confusion when recording dates in your family tree, it is best to use the month written in full or an alphabetic abbreviation such as Nov for November, rather than using a month number, such as 11 for November).

2. Failure to recognise and convert Julian dates to Gregorian dates

The Gregorian calendar was first introduced by Pope Gregory in Venice in 1582, and replaced the old Julian calendar. The new calendar altered the way that leap days were calculated and added days, so that the length of an average calendar year better matched the length of a solar year, ensuring that Christian religious festivals were celebrated at the correct time of year.

Different countries moved from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar on different dates. France, Spain and Portugal were early adopters in 1582. Most Protestant countries, however, did not accept the Gregorian calendar until the 18th century, such as Great Britain and its colonies in 1752. Some countries did not adopt the new calendar until the early 20th-century, such as Russia in 1918.

“The marriage took place today, July 7, 1903, of Szmelka Kurland… to Sura Rozenbaum …” This is an extract from a marriage record from the town of Miechow, Poland. According to the local calendar the marriage took place on 7 July 1903. However to interpret this properly, we need to understand that in 1903, Miechow was located in the Kielce province of the Russian Empire, and that Russia was still using the Julian calendar. There are several online Julian to Gregorian date converters. This gives the correct corresponding Gregorian date, used by most other countries in 1903, as 20 July 1903 – or 13 days later.

Do you have ancestors in your tree from various locations and time periods? If so, we recommend you enter the event’s main date according to the Gregorian date for consistency, but also to note the original Julian date.

Another common mistake in understanding the Julian calendar is to assume that the first day of the new year – the day on which year changed – was 1 January. Often it was not. For example, in England and its colonies, between 1155 and 1751, each new year started on 25 March! So, in England, the day after 31 December 1749 was 1 January 1749. And the day after 24 March 1749 was 25 March 1750.

This is illustrated by a list of 1749 burials for Norwich, Norfolk, England as recorded in the Norfolk Bishop’s Transcript registers (available on MyHeritage), see above. The burial entries are sequential and correctly show the burial of Anne, the wife of James Goodbody on 27 November 1749, before the burial of Bridget Howman, buried on 12 January 1749.

Dates between 1 January and 24 March were sometimes written as “double dates” – such as February 17, 1745/6 (where 1745 was the Julian Year). Some family historians prefer to write Julian dates in this double date format.

3. Misunderstanding dates from other special/religious calendars

Throughout the ages, and in different locations, many different calendars, in addition to Julian and Gregorian, have been used.

For example, from late 1793 until 1805 the French Republican/Revolutionary calendar was used in France. One objective was to remove religious influences from the calendar. Each week had 10 days with the 10th day of each week being a day of rest and festivity replacing the Sabbath. Each month had three weeks and there were 12 months in a year. In addition, at the end of each year, around mid-September, five or six extra days of festivities were added to make the year 365 or 366 days long. Again context is important; if you have a French document from this time, it is then important to convert the French Republican date to a Gregorian date to aid understanding. Fortunately, there are several calendar converters, including one within MyHeritage’s Family Tree Builder software.

Similarly, some religions have their own calendars. The Islamic or Muslim calendar is a lunar-based calendar of 12 months of 29 or 30 days, for a total of 354 days. Unlike many other calendars, there is no attempt to keep the festivals in the same season each year. Consequently, each year, Muslim festivals and dates occur some 11 days earlier in the Gregorian calendar than in the previous year.

The Hebrew or Jewish calendar is a lunisolar calendar. The months are lunar-based and have 29 or 30 days each. However, unlike the Muslim calendar, every two or three years a leap month is inserted into the year so that Jewish festivals continue to fall during the same season in each year. It is important to remember that each Hebrew calendar day starts at nightfall and lasts approximately 24 hours, so if an event starts during an evening then it is recorded with the Hebrew date of the following day.

The Hebrew inscription on the headstone above reads “Here lies the honorable Iser, son of (Mr.) Tzemach, died on the first day of the week [Sunday] 13 Sivan in the year [5]684. The Hebrew date can then be converted into the Gregorian date of 15 June 1924 using the conversion aid in Family Tree Builder, or date converters available online.

4. Confusing an event’s date and the date when it was registered or recorded

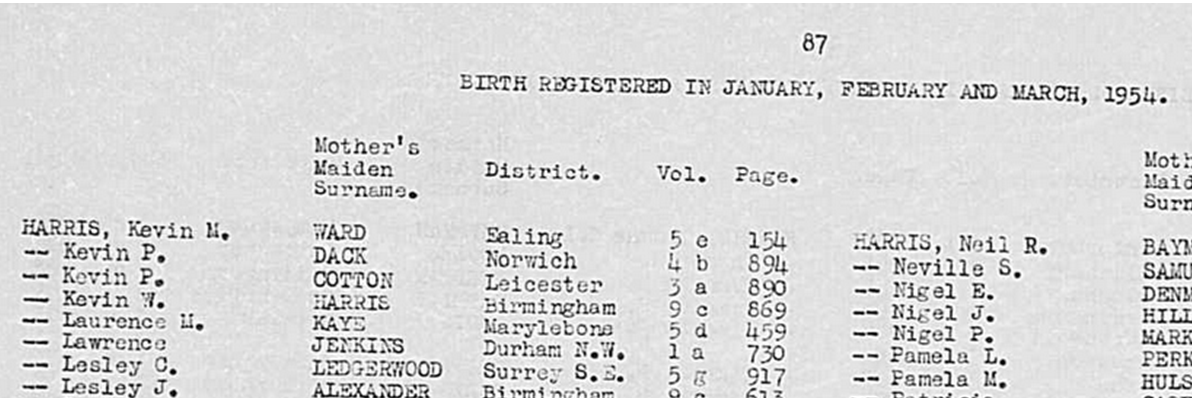

Events are often officially registered or recorded after the date when they actually occurred. In England, for example, there is a six week period following a birth during which time the birth should be registered. Also the indexes for English births for 1837-1983 were organised by quarter year, see below.

The birth entry for HARRIS, Kevin M., which appears in the register for January, February and March 1954, could well refer to a birth that occurred during the last six weeks of the year 1953 (and possibly even earlier if registration was not undertaken within the normal six-week period). It would be a mistake to conclude from this 1954 entry that the birth took place in 1954. One way to be sure would be to order a full birth certificate which would record the actual date of the birth.

5. Assuming that the dates in a document were recorded accurately

Documents may contain date errors for a variety of reasons. There can be errors if the respondent (who provided the information) never knew the accurate event date or their memory of the actual date has faded. In such a situation, the respondent may have guessed or approximated the date, especially if they were not present at the event. This happens frequently on death certificates when the deceased’s date of birth is required and the informant may know only the approximate age.

Also, when providing information, there could be reasons why the date might be deliberately falsified. Perhaps a person wanted to marry against the wishes of their parents but had not yet reached the required age, then they might have falsified their age or date of birth.

Errors also frequently occurred due to mis-hearing or mis-understanding by either the respondent or the person recording the information.

Consequently, a document’s dates and ages should ideally be cross-checked against other independent sources for the same data, for both reasonableness and consistency.

Summary

Always look at the original context of the event and, ideally, at the document in which it was first recorded to avoid errors in understanding as to when the event actually occurred.

For additional confirmation, especially where there may be doubt over its accuracy or interpretation, always try to find one or more additional independent documents relating to the same event.

When recording dates in your own records – if you standardize a date to a modern day calendar/standard – always note any change you have made with details of how the date was originally written and, where possible, include an image of the original text. This can be easily achieved when entering a fact into your MyHeritage family tree.

Have you come across any obstacles deciphering dates? Do you have other tips or mistakes to avoid? Let us know in the comments below.

Anne Smith

January 13, 2015

Thank you. very informative