Passenger Lists: A Gateway to Foreign Lands and a Former Life

- By Legacy Tree Genealogists ·

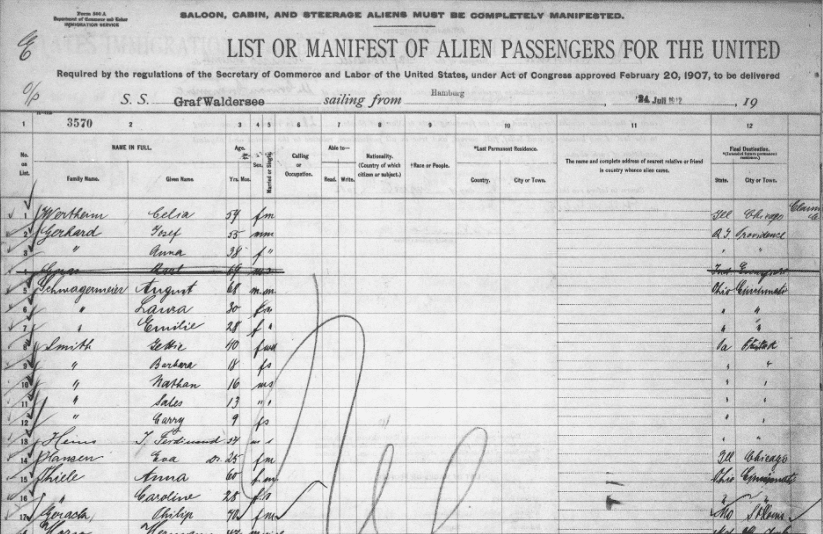

In the United States, I’ve heard it said that “unless your family is Native American your ancestors immigrated from somewhere.” How do you trace them if your family immigrated from one country to another, particularly crossing an ocean or two in the process? Their travels were likely documented, specifically on a passenger manifest for the ship they sailed on.

TIP: Search for Immigration and Travel records on the MyHeritage Immigration and Travel Database.

Early Immigration Regulation

A common family legend is that “Grandpa came over illegally in the 1840s and so there was no record of his arrival” or that “he stowed away so that’s why he isn’t in the passenger lists at Ellis Island.” While some of these stories may be true, the vast majority are not. The fact is, most immigrants were documented and it is a best practice to begin with the assumption that your ancestor was “the rule” rather than the exception.

However, it is true that until the mid-19th century very little effort was put into regulating who entered the United States, England, and many other countries. The following two statements attest to the lax situation:

“Although an Alien Act was passed in 1793 and remained in force to some extent or other until 1836, there were no controls between then and 1905 barring a very loosely policed system of registration on entry.” — England

“After certain states passed immigration laws following the Civil War, the Supreme Court in 1875 declared regulation of immigration a federal responsibility. Thus, as the number of immigrants rose in the 1880s and economic conditions in some areas worsened, Congress began to pass immigration legislation.” – United States

While early immigration was not regulated, emigration from a person’s home country was more heavily regulated. For example, in what is now Germany, a potential emigrant needed to register his intention with the local authorities, provide evidence of his identity and those leaving with him (e.g. a wife and children), prove that his debts were paid, that he had fulfilled his mandatory military service, and name a friend or relative who was willing to be responsible for any debts discovered after the emigrant was gone. This process took months and, in some cases, years before an emigrant was granted permission to leave. A whole family packing up and leaving would have been fairly obvious, so they had to follow this legal process. But a single person could sneak out of town fairly easily to avoid the inevitable red-tape. In some cases, a young man doing this might have been trying to avoid military conscription.

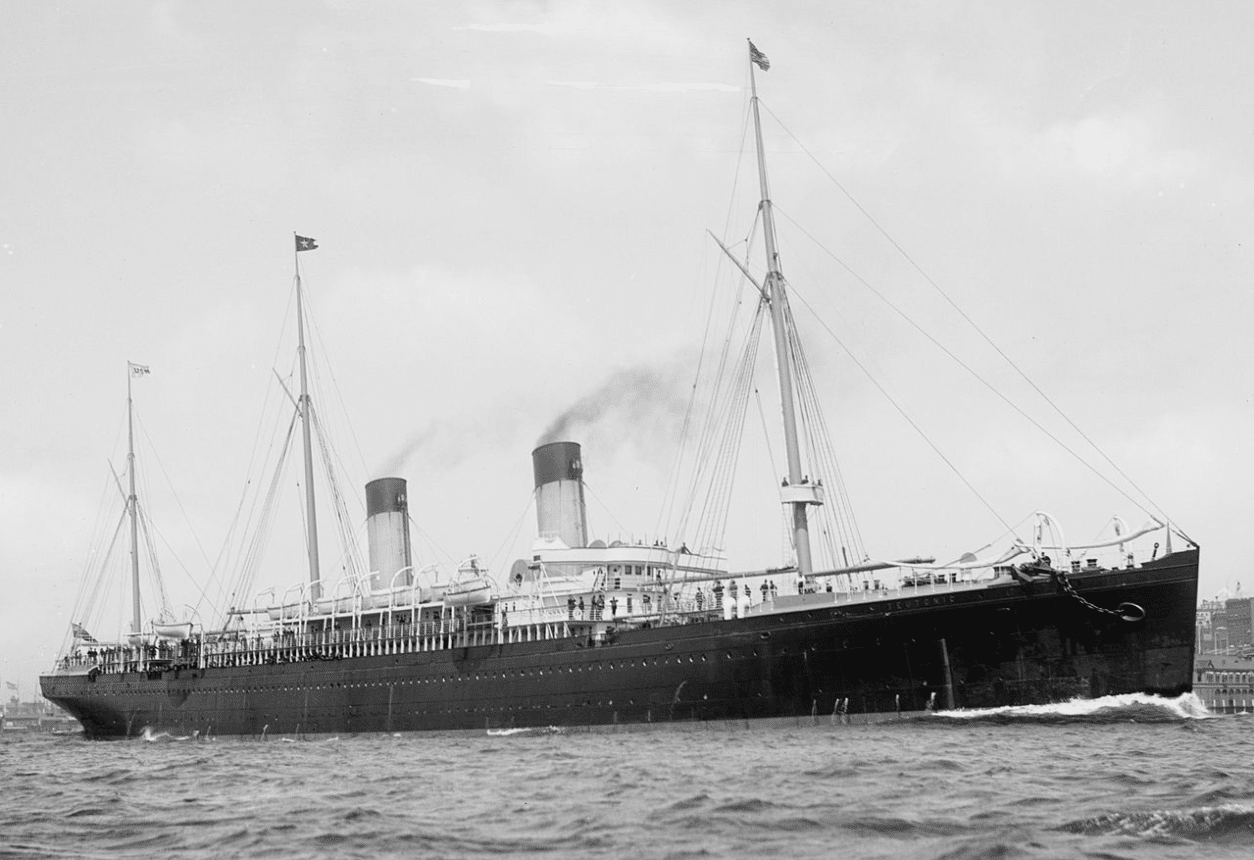

The arrival ports in many countries have preserved the records of immigrants arriving at their shores. Initially, this was so they knew approximately how many people were entering the country (for “taxation and representation” purposes) and so they could be somewhat assured these immigrants were not going to become a burden to the local economy. Later, these records were preserved for their historical and genealogical value. Because the departure ports were less concerned with who was leaving, along with record losses from European wars, their records are not as well-preserved. Departure lists from Hamburg, Germany and ports in the UK are the most available for genealogical research. However, if you know another port your ancestor left from make sure to check whether they also have extant records and how to access them.

How to Locate Passenger Lists for Your Ancestors

So, once you have researched your family back to their immigration date using censuses, vital records, church records, newspapers, and other resources, the next step is to find their passenger list. But how do you do that?

First, remember that if your ancestor came alone or provided inconsistent details about when and where they arrived, it may be harder to find the right immigrant in the passenger lists. It is always easier to know you’ve found the right immigrant if they arrived with family members, so keep track of extended family and close friends who may have arrived with them.

Second, remember that having only one correct spelling of your family surname is a modern construct—the census taker, the clerk at the port, and even the parish priest wrote the name phonetically as they heard it. So if your family name was Hungarian and the clerk was from Scotland, what he wrote down might not be what you think the name should have looked like. So make liberal use of wildcard searches (an asterisk * replacing groups of letters), remembering that vowels and unique letter combinations (like cz making the ch-sound) might best be replaced with that asterisk!

Finally, remember that other records might help you identify how they may have originally spelled their name:

Church Records

Immigrants often joined a religious community in their new residence. Often this was the nearest ethnically similar church—they might have even changed religions in favor of joining a parish that offered services and recorded events in the immigrant’s native language. So a family baptism, marriage, or burial recorded shortly after they arrived might include a version of the ancestor’s name that more closely matched the way it appeared on the passenger list.

Naturalization Papers

If your ancestor became a citizen after immigrating, their citizenship papers might state their name as: “current name (aka former name).” Naturalizations beginning in the 1920s in the United States also often included a Certificate of Arrival, which included the exact name they appeared under on the passenger list along with the ship name and date of arrival. So, finding their naturalization papers first may make it easier to identify their arrival in passenger lists.

Emigration Permission Records

If you know where your ancestor came from, find out if there are emigration permission records accessible for that area. You might be able to find details about when and where they intended to sail from their emigration file. This varies widely depending on the country—for example German emigration was regulated civilly, while Swedish emigrants often have a note in the Lutheran household registers that states they were going “to America,” with the year they left.

There are some immigrants who will not be identifiable in passenger lists because they traveled alone, their name was common, or the passenger list did not provide enough identifying information (especially true of passenger lists before the late-1800s). However, remember just because they can’t be found on a passenger list, that doesn’t necessarily mean they stowed away, or were shipwrecked, or something else just as exciting. Plus, there would likely be more evidence pointing to that kind of exceptional situation—such as a note in a naturalization file or a newspaper article. It could be that they simply arrived alone, that you haven’t thought of the right spelling to search, or even that you’re searching the wrong port or the wrong year. If all else fails, there are other ways to trace your immigrant ancestor back to their home country without it, so don’t despair. Your family story is waiting to be told!

Ready to learn more about your immigrant ancestors? Legacy Tree Genealogists can help you every step of the way. Legacy Tree Genealogists is the world’s highest client-rated genealogy research firm, and recommended research partner of MyHeritage. Founded in 2004, the company provides full-service genealogical research for clients worldwide, helping them discover their roots and personal history through records, narratives, and DNA. To request a free quote, visit: www.legacytree.com/myheritage

Penny Raymond

January 13, 2021

I do believe Deppers came over on Ellis island when I do not know