She’s certainly one of my S/Heroes!

As a Black military officer, it is imperative to soar above the fray of misogyny and racist US policies that unfortunately, still goes on today!

Bravo, Seour ♡Josephine!! ¡¡¡A bientot!!!

Performer, War Hero, and Civil Rights Activist Josephine Baker Is the First Black Woman Honored at the Panthéon

- By Esther

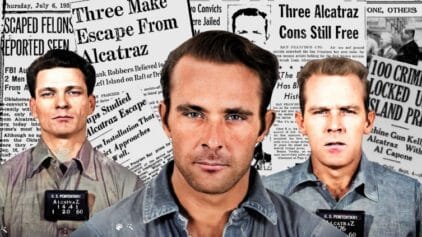

History is being made today: American-born French entertainer, war hero, and civil rights activist Josephine Baker will be the first-ever Black woman to be honored at the Panthéon mausoleum in Paris. She joins the ranks of almost 80 celebrated French heroes, including double Nobel-Prize-winning scientist Marie Curie and iconic writer Victor Hugo.

Josephine Baker was an extraordinary performer who used her talents and success to combat hate and injustice. Though she will remain in her final resting place in Monaco, a casket of earth from the U.S., France, and Monaco — the 3 places she once called home — will be placed in the famous mausoleum along with a plaque honoring her.

Rags to riches

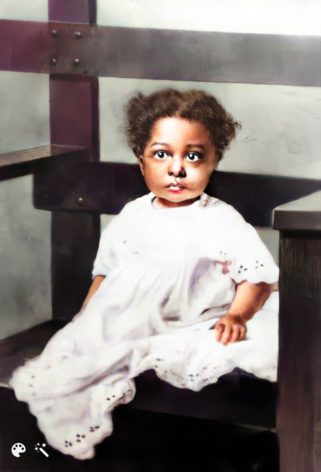

Josephine was born in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1906, to a single mother who struggled to clothe and feed her.

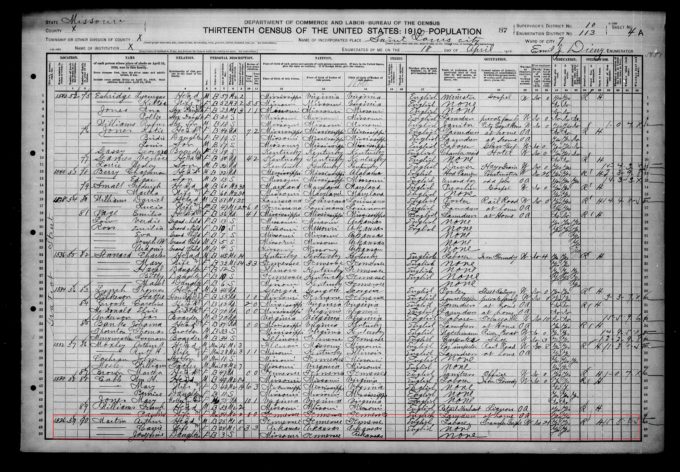

Josephine at age 3 living with her stepfather Arthur Martin and mother Carrie in the 1910 U.S. Census on MyHeritage (Click to enlarge)

At only 8 years of age, Josephine began working as a live-in domestic for white families. She dropped out of school at age 12 and at 13 was working as a waitress and a street-corner dancer to make a living. She got married at age 13, but divorced less than a year later. Her second marriage at age 15 was to William Howard Baker, and though she left him and they divorced in 1925, she kept using his name professionally.

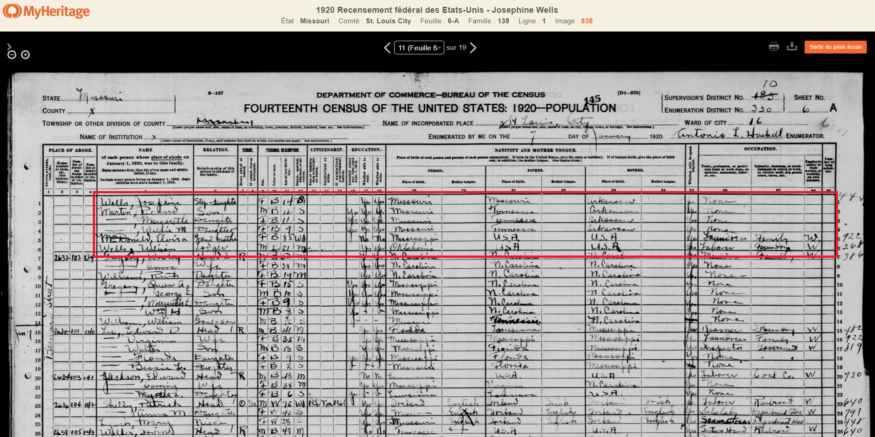

Josephine, at 14, after taking the name of her first husband, William Wells, 21, mentioned in the 1920 U.S. Census alongside Josephine’s half-brother Richard, 12; her half-sisters Margaret, 11, and Willie May, 9; and her maternal grandmother Elvira McDonald, 85 (Click to enlarge)

Josephine knew she was destined for greater things and at age 13 she convinced a show manager to recruit her for the St. Louis Chorus vaudeville show. But her real first big break came when she sailed to Paris at age 19 and opened in La Revue Nègre and the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées. She became an instant success there as an erotic dancer, famously appearing in a skirt of artificial bananas and a beaded necklace. Though very popular in France, she wasn’t nearly as well-received back home, and she eventually renounced her American citizenship and became a French citizen instead.

See Josephine perform her first song “J’ai deux amours”:

While her accomplishments in the entertainment industry are admirable, her nerve and daring extended far beyond the stage. And when the shadow of World War II fell over her beloved adopted home, Josephine wasn’t going to stand by idly.

Resisting the Nazis

In September 1939, Josephine joined the Deuxième Bureau, the French military intelligence agency. As an “honorable correspondent,” she socialized with Germans at embassies, night clubs, and social events, exercising her fame and personal charm to secretly gather information for the French.

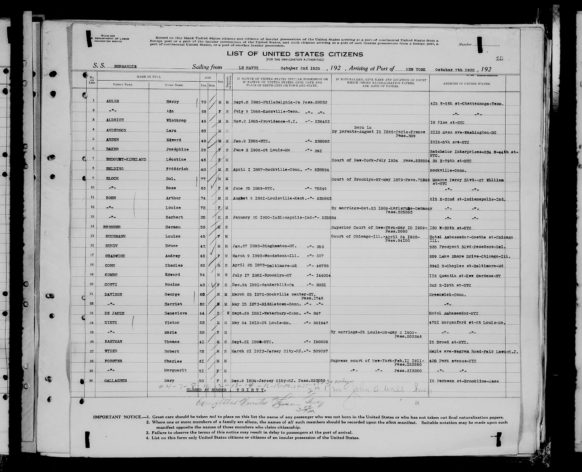

Josephine mentioned in the Ellis Island Passenger Lists and Other New York Lists, 1820-1857 collection on MyHeritage (click to enlarge).

After the Germans invaded France, Josephine refused to perform for them. She left Paris and housed members of the Free French effort in her home in Dordogne, supplying them with visas. She leveraged her status as an entertainer to move freely around Europe and South America and transmit information to the Allies about German airfields, harbors, and troops in western France, using notes written in invisible ink on her sheet music. She even pinned notes with gathered intelligence in her underwear, relying on her celebrity status to avoid a strip search. She also raised funds for the resistance, sometimes contributing from her own fortune.

Josephine was awarded a number of military honors for her work during the war, including the Croix de guerre, the Rosette de la Résistance, the Commemorative medal for voluntary service in Free France, and the Resistance medal. She was also “knighted” as a Chevalier of the Légion d’honneur by General Charles de Gaulle.

Josephine Baker in her military uniform. Photo colorized with MyHeritage photo tools. Original photo by Studio Harcourt

Fighting racial inequality

After the war, Josephine’s career reached new heights, and in 1951 she was invited back to the United States. The tour started out spectacularly, with rave reviews and enthusiastic fans — but was interrupted by an incident in the Stork Club in Manhattan. Despite her stardom, she was refused service at the club. Josephine — who all along had been refusing to perform in segregated venues — criticized the club and accused them of racism. In the aftermath, she was accused of Communist sympathies and her work visa was terminated, forcing her to cancel the rest of her engagements and go back to France. She wasn’t allowed to return to the United States for almost a decade.

Josephine was shocked and infuriated by her treatment and by the blatant racism she saw in the U.S., and she became a civil rights activist, working with the NAACP, attending rallies, and speaking out in support of the cause. In 1963, she spoke at the March on Washington alongside Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. At this rally, where Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech, Josephine was the only official female speaker. She introduced Rosa Parks and Daisy Bates among other Black women fighting for civil rights.

In her speech at the event, Josephine spoke about the contrast between her experiences in the U.S. and in France: “I have walked into the palaces of kings and queens and into the houses of presidents, and much more. But I could not walk into a hotel in America and get a cup of coffee, and that made me mad. And when I get mad, you know that I open my big mouth. And then look out ‘cause when Josephine opens her mouth, they hear it all over the world.”

Josephine Baker appears in a Brazilian consular file during a visit to Brazil in 1952. From the MyHeritage historical record collections

‘The Rainbow Tribe’

During her work in civil rights activism, Josephine began adopting children from different ethnicities, forming a family she called “The Rainbow Tribe.” She wanted to prove to the world that people of different ethnicities and religions could still live together as siblings. Her children were from France, Morocco, Korea, Japan, Colombia, Finland, Algeria, the Ivory Coast, and Venezuela, and some were raised in different religions. She brought her children with her on tours, but when they were together at her home in Dordogne, she arranged tours so people could come and see how happy they were together.

In her later years, Josephine suffered from some financial problems and lost her properties. Princess Grace of Monaco — who had actually been present and supported Josephine during the Stork Club incident years ago — offered her a place to live with her children. In 1975, after a successful opening to her comeback tour, she fell into a coma and eventually passed away.

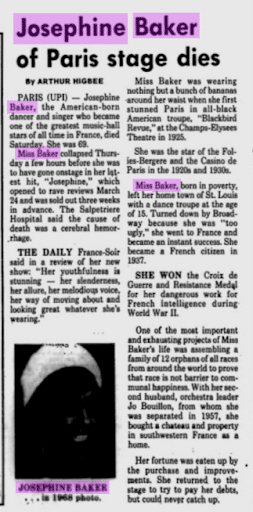

Article from the St. Petersburg Times announcing Josephine’s death on April 13, 1975. From the MyHeritage Newspaper Name Index collection

There is no doubt that she lived a vibrant and extraordinary life, and was deeply committed to her adopted home — France — as well as the welfare of all of humankind. The Panthéon is all the richer for adding her legacy to the ranks of the French heroes and heroines it honors.

If you have any French heritage, MyHeritage is the place to research it: we recently added millions of historical records from France! Click here to search the French collections on MyHeritage.

Diane Farrington

January 4, 2022

We were lucky enough to visit Josephine Bakers Chateau in France. What a beautiful place for an amazing woman. Xxx