This is a guest post by Legacy Tree Genealogists. They provide full-service genealogical research for clients worldwide, helping them discover their roots and personal history through records, narratives, and DNA. Based near the world’s largest family history library in downtown Salt Lake City, Utah, Legacy Tree has developed a network of professional researchers and archives around the globe. For additional information on services visit www.LegacyTree.com.

This is a guest post by Legacy Tree Genealogists. They provide full-service genealogical research for clients worldwide, helping them discover their roots and personal history through records, narratives, and DNA. Based near the world’s largest family history library in downtown Salt Lake City, Utah, Legacy Tree has developed a network of professional researchers and archives around the globe. For additional information on services visit www.LegacyTree.com.

Genetic testing is today an increasingly integral part of the family history and genealogy industry and is often considered essential as part of the reasonably exhaustive search required for the Genealogical Proof Standard (GPS).

In this introduction to DNA testing for family history, we’ll outline the basics—the different types of DNA, reasons to take a DNA test, and real-life applications and successes.

DNA Types and Tests

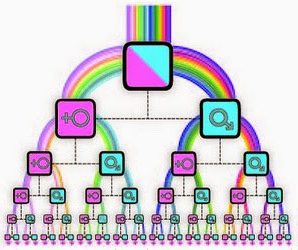

The yDNA test has been used for genealogical purposes for over 10 years. The test gets its name from the Y-chromosome. The Y-chromosome is only carried by males and is inherited in a line of direct paternal descent. from father to son. A male receives his Y-chromosome from his father, who inherited it from his father, and on and on. Occasional minor mutations help to distinguish different Y-chromosome lineages. Because surnames are often inherited in a similar pattern in many cultures, two individuals with the same surname and similar Y-chromosome signatures share a common direct line paternal ancestor. Likewise, two individuals with different surnames, but who share the same Y-chromosome signature, share a common direct line paternal ancestor. This situation may be indicative of a “non-paternal event (NPE),” which could include an undocumented adoption, illegitimacy, a surname change, or other situations which might result in the paternal surname not being passed to both lines of descent.

The mtDNA test is similar in many ways to a yDNA test. The short term for mitochondrial is “mt,” and identifies where in the cell this type of DNA is located – in the mitochondria. All other DNA is located in the cell’s nucleus. Mitochondrial DNA is carried by both males and females, but it is only passed on by females. Therefore, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is inherited along the direct maternal line. An individual receives his or her mitochondrial DNA from their mother who received it from her mother. Occasional mutations help to distinguish different mitochondrial DNA lineages. If two individuals share a mitochondrial DNA signature, it may be indicative of shared maternal ancestry. Because mitochondrial DNA is much smaller than any other type of DNA, and because it undergoes fewer mutations over time, it is more difficult to make genealogical discoveries with this test. It is best used to offer support for genealogical hypotheses.

The atDNA or autosomal DNA test is designed to look at over 700,000 DNA markers that can be found on a person’s “autosomes,” the 22 pairs of non-sex chromosomes found inside the cell’s nucleus. Autosomal DNA tests analyze portions of the DNA that are inherited both paternally and maternally. Each person receives half their atDNA from their mother and half from their father. atDNA undergoes a process called recombination, which shuffles the maternal- and paternal-inherited copies of DNA before passing them to the next generation. Each person receives half of their atDNA from each parent, but only approximate percentages can be applied to more distant generations of ancestors due to the random nature of recombination. Each individual shares about 25 percent of their DNA with each grandparent and half that amount for each previous generation. Individuals who share large identical segments of atDNA most likely share a recent common ancestor. Autosomal DNA testing has become popular over the last few years, and most ancestral DNA tests are autosomal tests.

The X-chromosome is another type of DNA that has a unique inheritance pattern. Males receive one X-chromosome from their mother. Females have two X-chromosomes (one from their mother and one from their father). The X-chromosome undergoes recombination in females, but not in males. Though the X-chromosome cannot be assigned to a specific line of descent, it can be used to eliminate individuals from a person’s tree as possible common ancestors to their matches. The X-chromosome is included in the autosomal DNA test.

Reasons to Test

We recommend that there be a specific genealogical goal or research question prior to completing a DNA test, just as there should be a specific objective in mind when undertaking traditional research. Once this question or goal is determined, then advice can be provided regarding which test to take and whom to test.

In some cases, good, old-fashioned genealogical research may provide the best answers to the questions asked. In other cases, DNA may provide the only evidence or proof of suspected relationships and answers to questions. In most cases, combining genealogical research and results of DNA testing analysis are combined to provide solid proof arguments regarding genealogical research questions.

DNA testing can be useful for answers to questions regarding adoption, illegitimacy, unknown or misattributed parentage, name changes, immigration, and many other instances of difficult-to-trace ancestry.

While DNA tests have the ability to help investigation in these difficult situations, they may also reveal well-kept family secrets. Whenever a DNA test is taken, there is the possibility of discovering previously unexpected relationships through undocumented adoptions and illegitimacy. These discoveries can be surprising and may drastically change the way you view and approach your family history. Testing companies and private researchers do not bear responsibility for these discoveries or the impact that they may have on individuals and families.

Genetic Genealogy Success

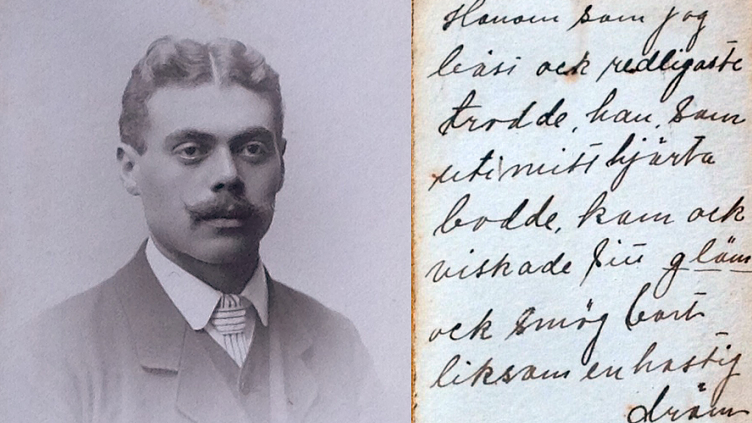

Many adoptees have successfully identified their birth parents through genetic testing and other available resources. However, genetic testing can also be helpful for genealogical questions. Many have successfully used yDNA in conjunction with atDNA – and the historical records – to identify fathers of illegitimate ancestors. Others have used atDNA to overcome recent genealogical brick walls. Other researchers have used mtDNA to support descent from common maternal ancestors or to confirm or refute family legends regarding African or Native American ancestry.

In one recent case, we were able to reveal the identity of a client’s second great-grandfather through atDNA. A concealed illegitimacy had prevented previous contact with part of the client’s family and, as a result of testing, we were able to extend the client’s ancestry several generations. Although we answered the client’s research question, it also opened new avenues of investigation since the family has not yet been able to determine the origin and parentage of their common second great-grandfather, born in the early 1850s in Missouri. DNA testing and collaboration with the newfound cousins may help to reveal this individual’s ancestry through future research.

Applications of DNA testing to genealogical investigations are many and varied, and they are also frequently successful. However, even when tests do not yield immediate results, as more people test and more matches are identified, genetic genealogy tests become sources that keep giving.

Exclusive Offer for MyHeritage Users: Receive $100 off a 20-hour research project using code SAVE100, valid through April 5, 2017