![[Guest Post] Commemorating the Titanic](https://blog.myheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/featured/624130346136titanic4_zoom-872x472.jpg)

![[Guest Post] Commemorating the Titanic](https://blog.myheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/featured/624130346136titanic4_zoom-872x472.jpg)

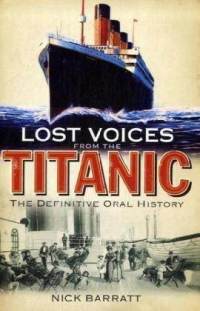

This is a guest post from Dr Nick Barratt, (author, historian and broadcaster) who runs Sticks Research Agency and is a regular presenter of TV shows as well as his own vodcast www.familyhistoryshow.net, in association with MyHeritage.com. He currently serves as the President of the Federation of Family History Societies, Vice President of AGRA, Executive Director of FreeBMD, Editor in Chief of Your Family History magazine, Honorary Teaching Fellow at the University of Dundee, and Trustee at the Society of Genealogists.

Don’t forget to send your family’s Titanic stories to stories@myheritage.com by Friday for your chance to win a copy of Dr Barratt’s book – Lost Voices from the Titanic.

2012 is meant to be a year about celebration. We have the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee and the London Olympics, shaping the tone of our approach to public occasions – a chance to forget the doom and gloom surrounding the economy and have a party.

Maybe that explains some of the celebratory noises associated with the centenary of the Titanic’s maiden voyage, and subsequent place in the annals of maritime history when it struck an iceberg and sank. As this anniversary approaches, it is terribly easy to forget the horrific loss of life – over 1,500 people died in a few minutes – as plans are made to re-release the Hollywood blockbuster, hold events and exhibitions, even street parties in a couple of locations.

In the main, though, the feeling is of commemorating rather than celebrating this moment of contemporary history. I have a personal bias towards this approach, having written the book – Lost Voices from the Titanic – which features eyewitness statements rarely used or published in their own right, having been collated by historian Walter Lord in the 1950s, as he wrote his own account of the tragedy, made into a haunting film, “A Night to Remember.”

The majority of the collection is at the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, and it is distressing to read. Each one transports the reader back in time to that fateful night, placing you where the people themselves stood – on the deck waiting for instructions, in the bowels of the ship trying to save the stricken vessel, in the communications room frantically trying to raise the alarm and secure rescue, and in the lifeboats, watching the ship sink below the icy waters of the Atlantic.

You cannot help but be moved by some of these accounts. Among the most poignant and eloquent is Charlotte Collyer, who watched her husband Harvey remain on board as the lifeboat containing her and their daughter, Marjorie, descend towards relative safety, knowing there was little chance of seeing him again. She describes the emotional scene as a young lad tries to jump in with them, and is ordered at gunpoint by the officer on board to leave the ship and act like a man; sobbing, the youth leaves to meet his fate. She transports us to the deck of the Carpathia, the first ship on the scene, as women desperately tried to see if their husbands had made it to safety, in the main to be bitterly disappointed as she was. Her story ends with a letter back to her parents-in-law, grief stricken and having to face the journey home having lost everything but her daughter.

I was fortunate enough to meet the last surviving passenger, Millvina Dean, before she passed away in 2009. She summed up the way I think we should approach the Titanic; it changed her life in so many ways, but she cannot bear the thought that people would visit the wreck, or bring up objects from the sea bed. “After all,” she said, “that’s my father’s grave. He lies down there, somewhere. Let him rest in peace.”

Now that the last living link with the ship has passed away, we should commemorate the centenary, and only then begin to look afresh now that the Titanic has become part of history, not a living reminder of personal tragedy.

Laura Mabel Francatelli and Other Survivors (Taken from the Discovery Channel - http://dsc.discovery.com/news/2007/04/05/titanicslide_03.html)