What a beautiful story.

The Three Stevens Brothers: An Extraordinary Transatlantic Bond Formed in Memory of a Fallen D-Day Soldier

- By Elisabeth Zetland ·

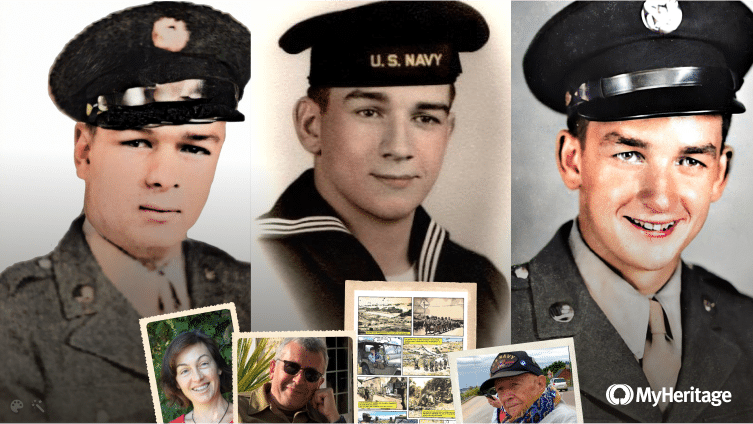

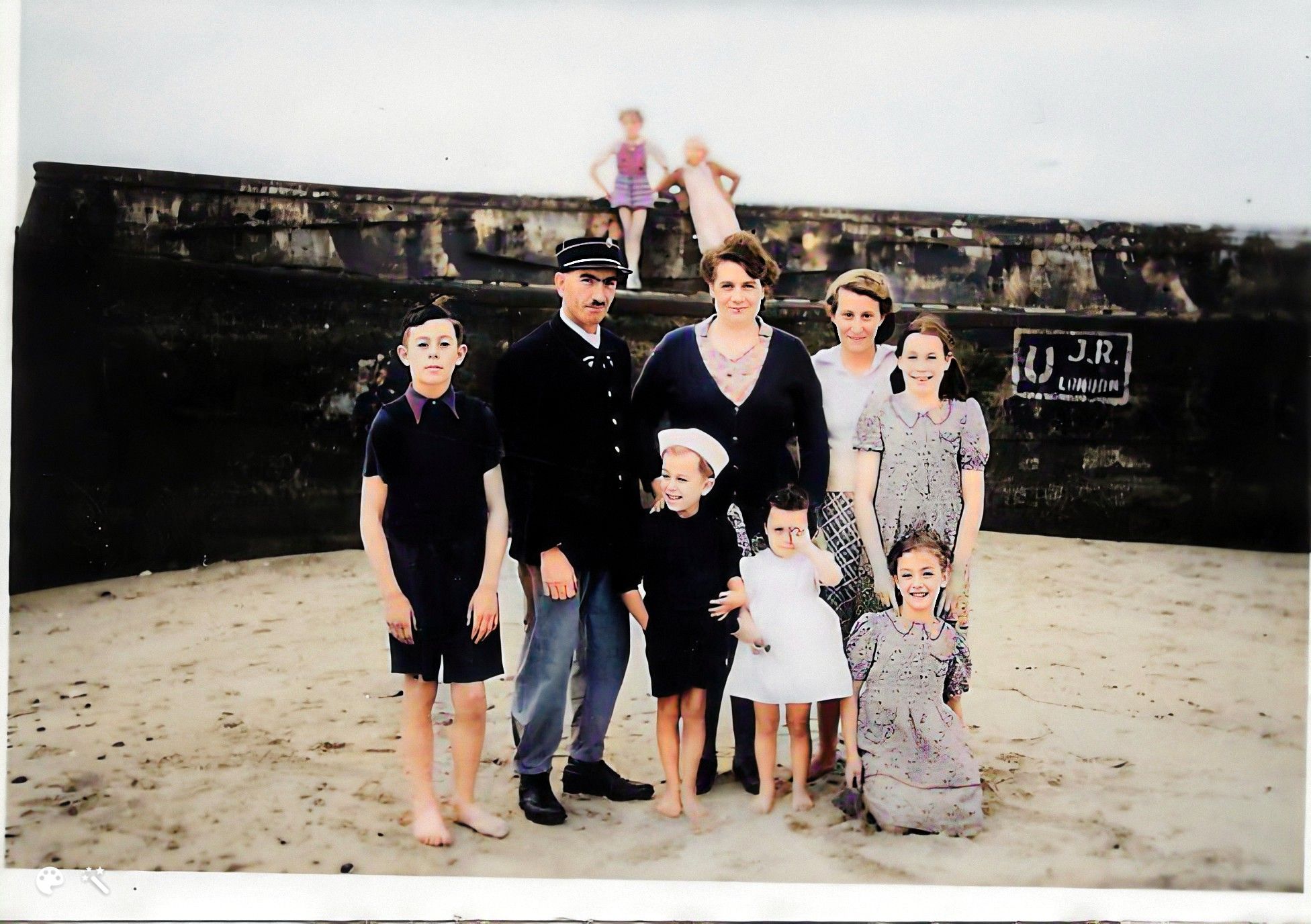

Since the end of WWII, a beautiful and incredible friendship has connected the family of Sylvie Laillier, a French user from Normandy, and an American family from Pennsylvania that sent 3 sons to fight in the war. Two of them, Paul and William Stevens, did not return. The third, Donald Stevens, now 97 years old, cherishes this unwavering bond that unites them despite the years that pass and an ocean that separates them. For the 80th anniversary of the D-Day landing on June 6, we are honored to tell you their story, which Sylvie’s cousin, Ludovic Adeline, has just published in a magnificent comic strip. Their story was also recently covered in the Washington Post.

Sylvie’s family comes from Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer, a town in Calvados in Normandy, which borders Omaha Beach. This same beach is nicknamed “la sanglante” (“the bloody”) because of the many men the Allies lost during the Normandy landings on June 6, 1944.

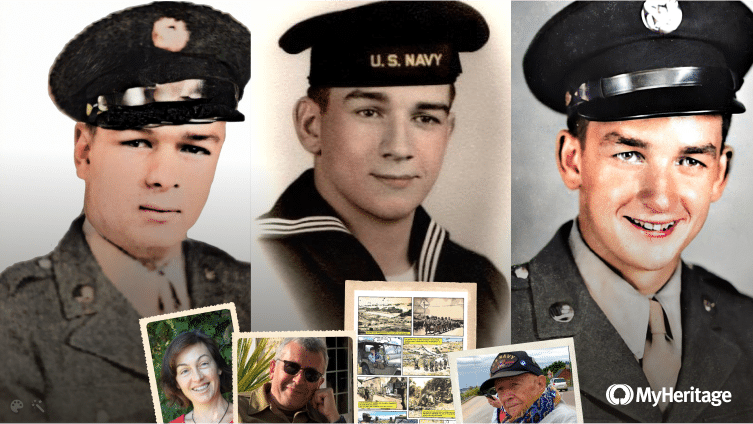

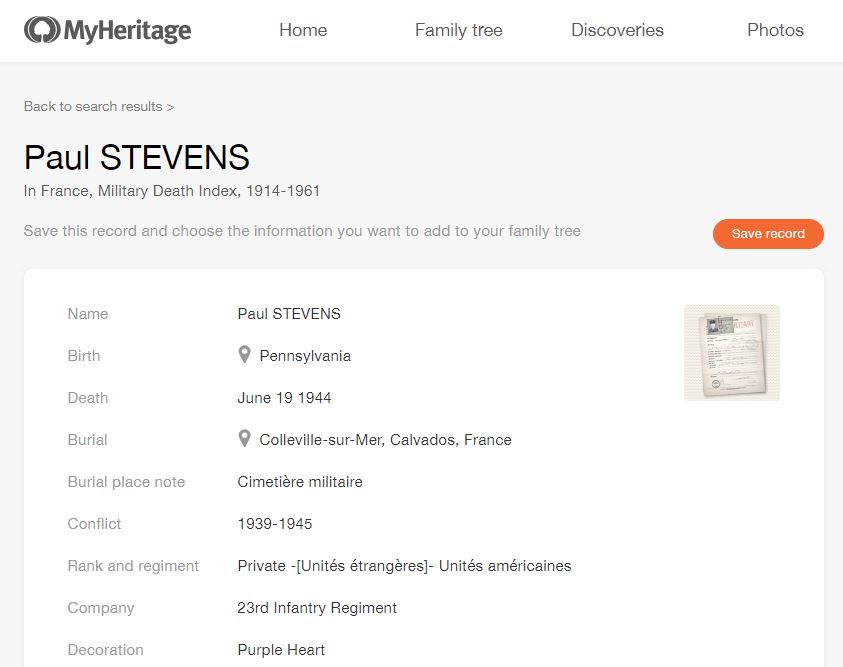

One day in 1946, a letter arrived at the Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer post office. The sender was Lillian Stevens, an American mother who had lost two sons in the war. Her eldest son, Paul T. Stevens, landed at Omaha Beach and was killed on June 19, 1944.

“I have a son buried in the U.S. Military Cemetery at Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer, France. If there is any possible chance, I would like to hear from the person who cares for his grave. We are told they are often cared for by private families,” she wrote. In the letter, she also mentioned her second son, William, who was killed in action in Germany on April 1, 1945.

Mrs. Stevens’ letter dated May 23, 1946 and addressed to the postman from Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer (recto)

‘Family beyond belief’

Sylvie’s grandfather, Charles Olard, was the postman of Saint-Laurent. Touched by Mrs. Stevens’ letter, he decided together with his wife Germaine to locate the grave and send a letter to the grieving mother, attaching a photo of the grave. From that moment, an extraordinary bond was forged between the two families which has lasted for 80 years, still nurtured today by the families of the grandchildren of Charles and Germaine Olard and the third Stevens brother, Donald, who survived the war.

“I think my grandparents also put a handful of soil taken from around Paul’s grave in the envelope,” says Sylvie. “Today, my family still brings flowers to his grave.”

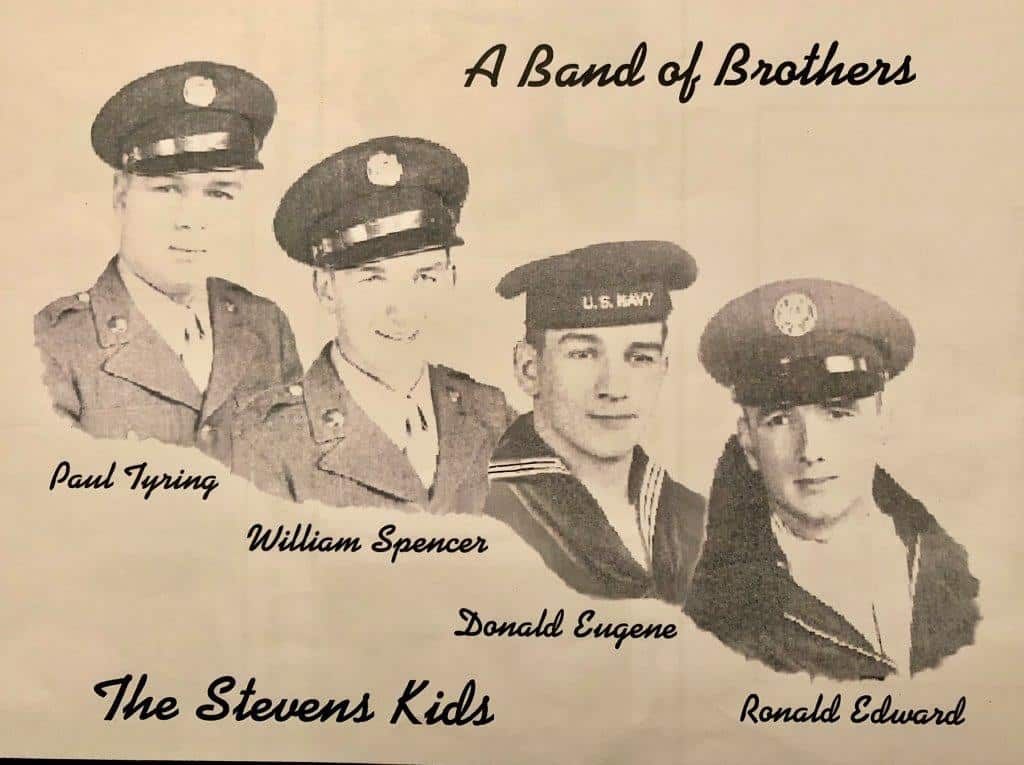

“I was the third son in my family, and being only 5 years apart, we grew up like triplets,” Donald recalls. “I was the only one to come back home safe, and I felt lost and confused about my future. The new extended French-American family that emerged in 1944 made the old axiom ‘Sometimes you have to lose to win’ a reality. Our story is filled with so much love and trust in each other that we are family beyond belief. I don’t know if I’m more American or French but I claim dual nationality, one on paper and one in my heart.”

In this video, Donald Stevens and his son Scott speaking about his brothers and the link that unites him to France:

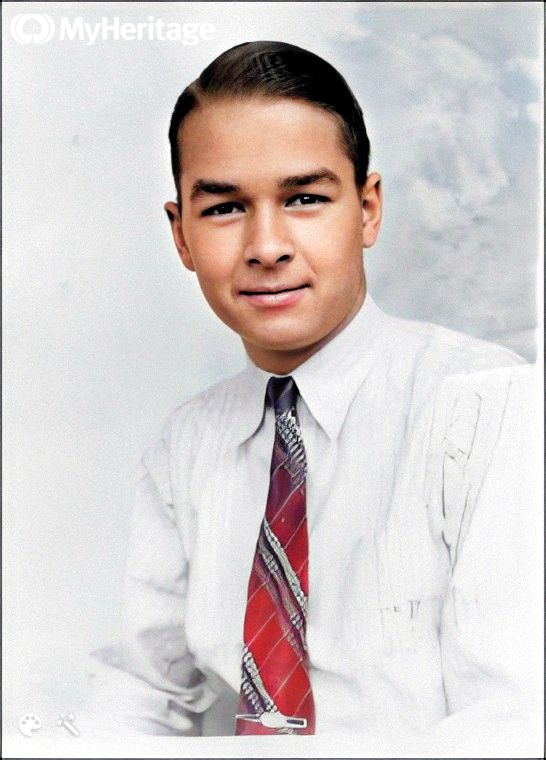

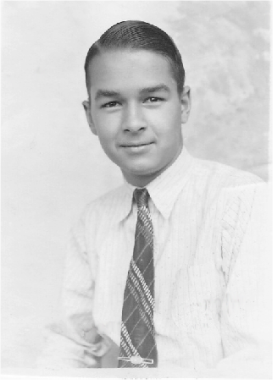

Paul’s story

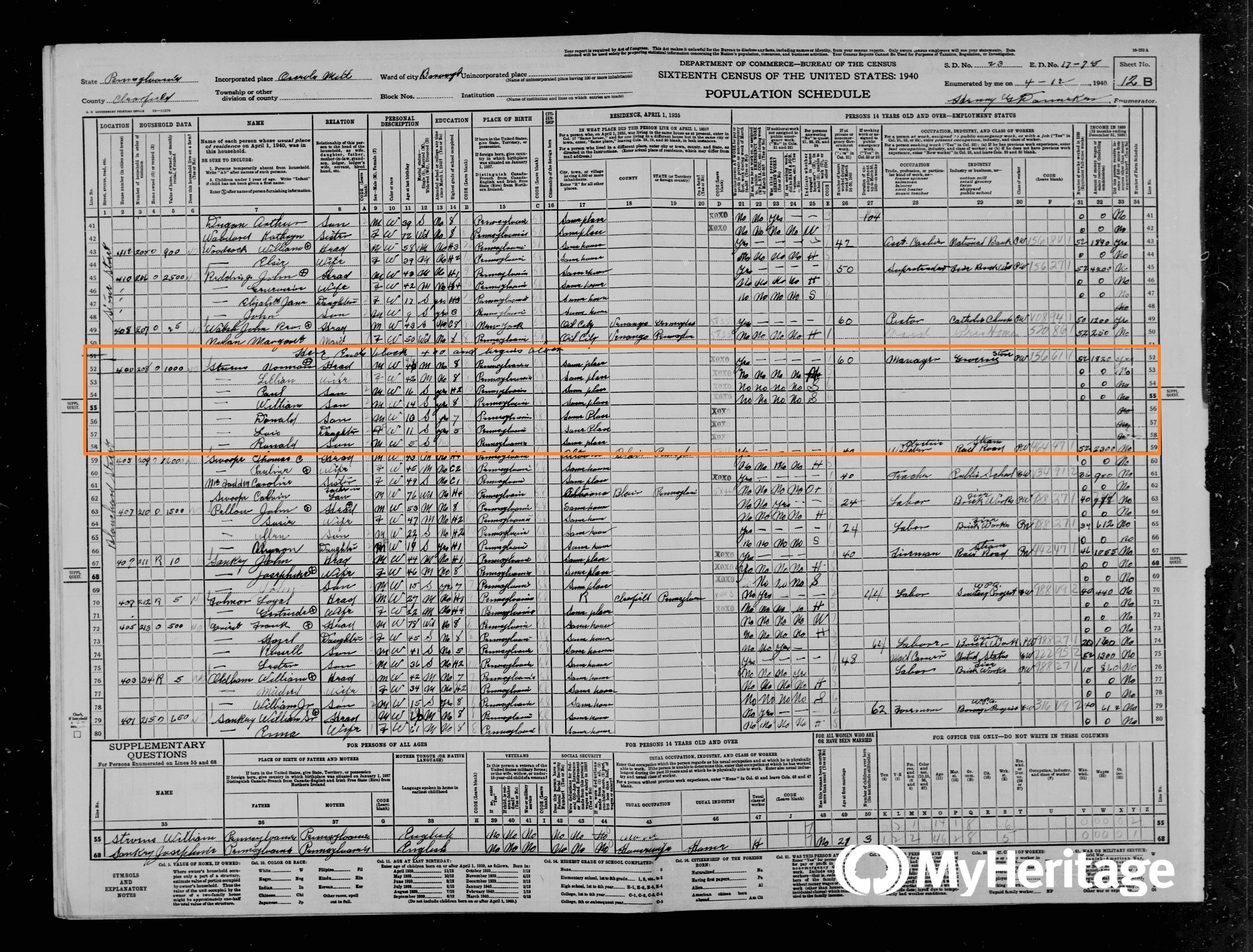

The Stevens family hails from Osceola Mills, a small town in Pennsylvania which had a population of 2,000 in 1940. A thousand of them went to war; 35 did not return. The 3 eldest sons, Paul, William, and Donald, enlisted one after the other when America entered the war.

The Stevens family in the 1940 U.S. census: Norman and Lillian Stevens with their 4 sons, Paul, William, Donald, and Ronald, and their daughter Lois. (Donald was 13 years old and not 10 as mistakenly stated.)

Paul, the eldest of the siblings, enlisted in March 1943. The Stevens proudly displayed a flag with a blue star in their window indicating that a member of the family was serving in the army. It was Paul’s first time away from his family. After he trained for a few months, he came home for a leave before departing for Europe, and his family noticed that the eczema which always plagued had completely disappeared.

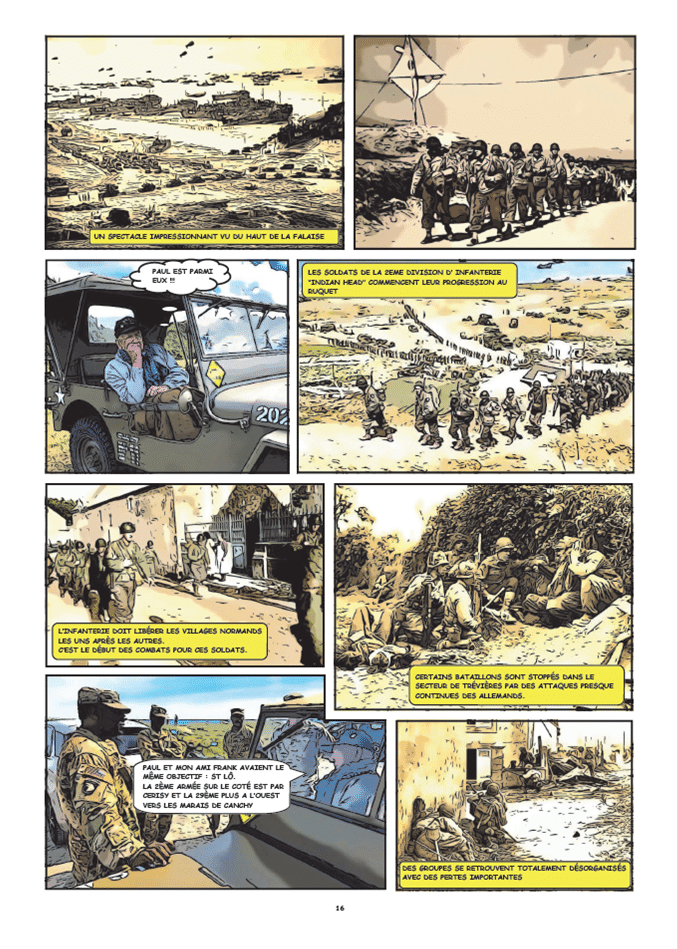

A Private in Company K, 23rd Infantry, 2nd Division, he arrived in Ireland in September 1943 and was in England in May 1944, where his unit trained for D-Day. He landed at Omaha Beach on June 7, 1944. Their mission was to liberate the villages of Normandy; the objective: Saint-Lô. The battles were tough, their losses were significant, and progress was slow.

On June 13, Paul and his group suffered a violent German counterattack at Saint-Georges-d’Elle. From the top of the hill overlooking this village, German artillery shelled the American troops. This was the last village that Paul went through.

On the way to Hill 192, the fighting was just as violent. The Germans fought fiercely to prevent the Americans from taking Saint-Lô. As shells rained down on them, Paul took cover in a ditch. He was killed instantly. It was June 19, 1944; he was 20 years old.

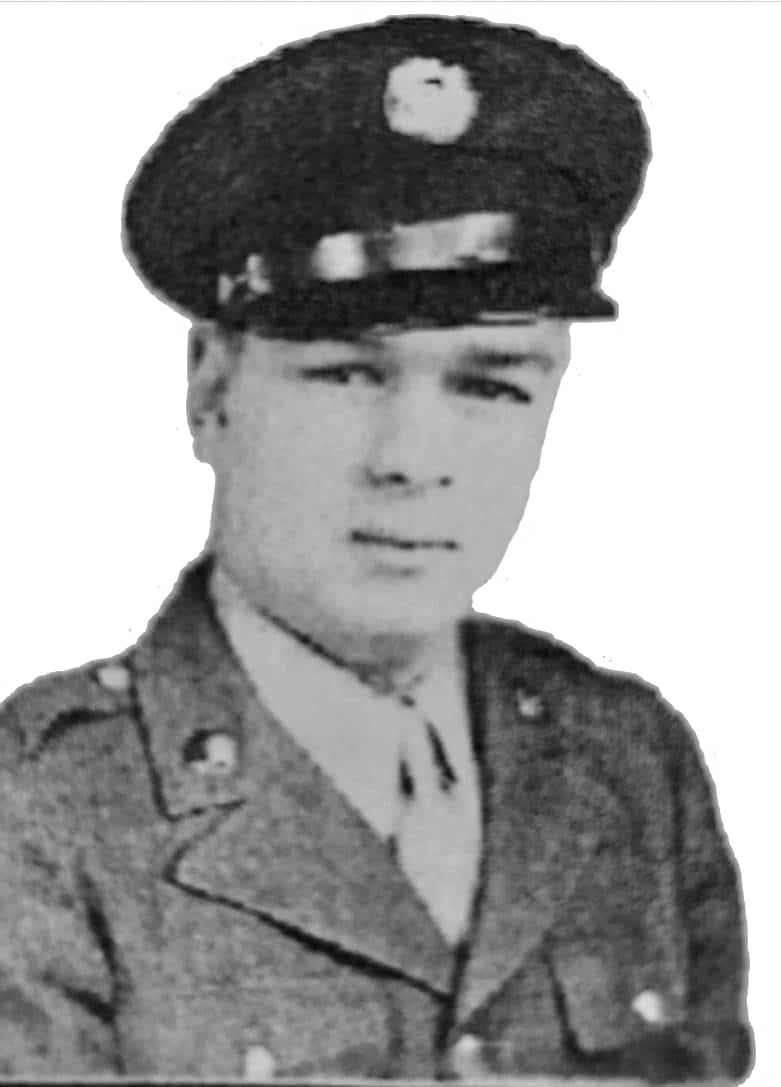

Bill’s story

When he learned of his brother’s death, William wanted to avenge him and wrote a heartbreaking poem for Paul which ends like this:

“He cannot come back

It’s now up to me,

To go where he’s gone

So together we’ll be”

The blue star on the Stevens’ window flag changed to gold, signaling the soldier’s death, but a new blue star joined it as William managed to enlist — despite an initial rejection due to a stain on his lungs. William persisted, even hiding a painful foot infection he contracted, and he was finally recruited in October 1944.

He arrived in France in February 1945, and joined General Patton’s 3rd Army. His feet hurt so much that he could no longer take off his boots. The simple act of walking was torture, but he didn’t think of giving up for a moment. He wanted to continue what his brother started.

In the spring of 1945, the fighting was intense, but the Allies advanced quickly towards Berlin. On Easter Sunday 1944, April 1, while crossing the town of Helmstedt in Lower Saxony on a half-track, William and four other soldiers were killed by a shell. They were all 19 years old. They are buried together at Arlington U.S. Military Cemetery.

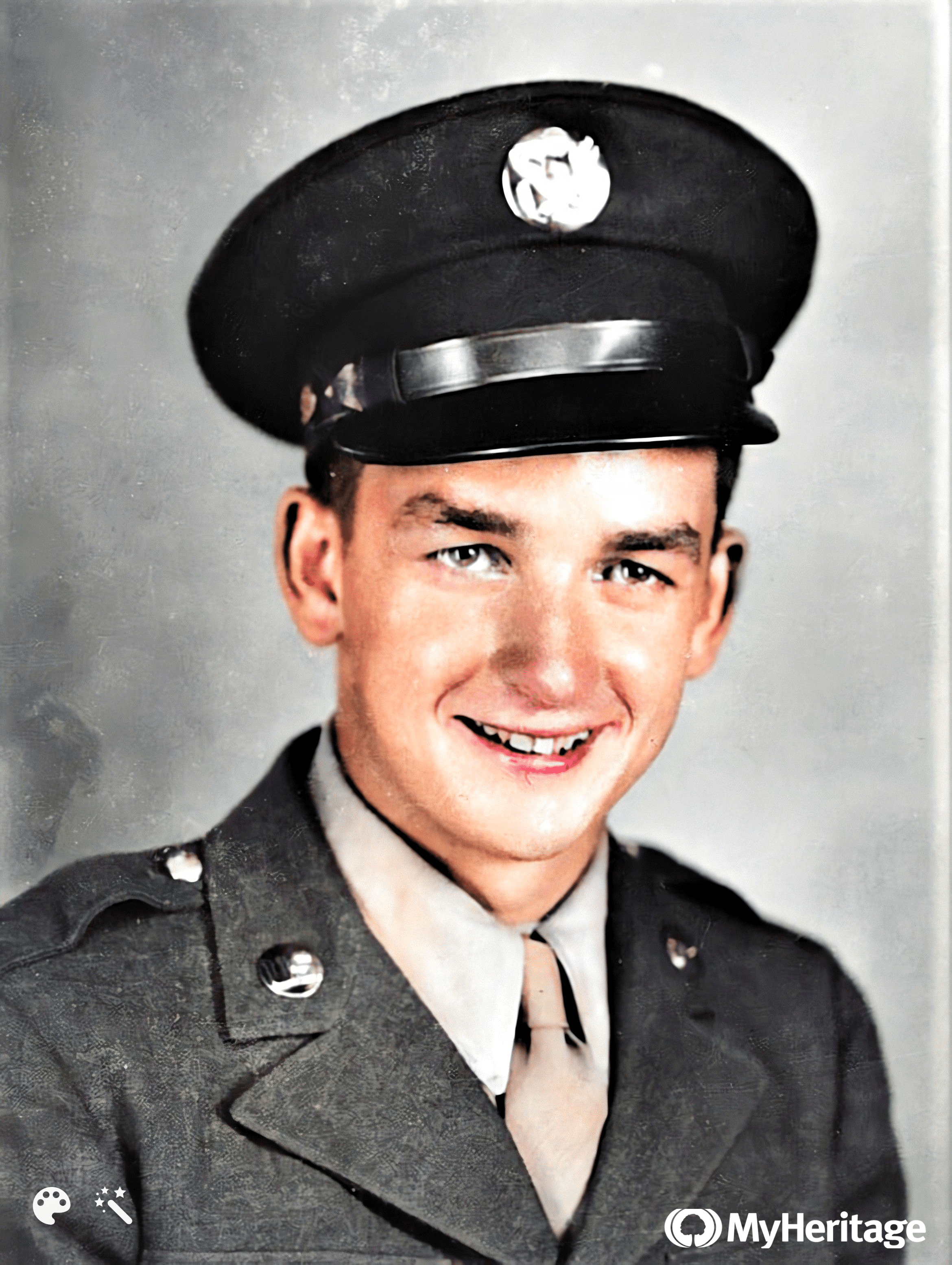

A new gold star adorned the Stevenses’ flag, but in the meantime, another blue star had appeared: the third brother, Donald, had also enlisted. Aged 18 in 1945, he was in the Navy and about to be sent to the Pacific when news broke of William’s death. Donald was determined to fight, but because his parents had already lost two sons, the army sent him home.

An extraordinary correspondence

Lillian Stevens and Germaine Olard exchanged letters until Lillian’s death in 1959. As the Stevenses did not speak French, each letter was translated by a French teacher at the local school. The Olards knew some English and a woman from their village helped them read Lillian’s letters.

“This correspondence helped my mother cope with her grief during the last years of her life,” Donald says today.

During the last few years of her life, Lillian Stevens experienced the anguish of having another son in the army. Her youngest son, Ronald, who is now deceased, served for several years between 1955 and 1961.

After Lillian’s death, the families stayed in touch by mail. Then, in 1975, Germaine and Charles’ daughter initiated their first in-person meeting in the United States. This was the first of several visits to the United States and France.

This moving story has just been published as a comic book by Ludovic Adeline, grandson of Charles and Germaine Olard and first cousin of Sylvie Laillier. A retired bookseller, he wanted younger generations to understand the sacrifices of those who came before them, while celebrating the friendship between the American Stevenses and his French family. Entitled The Three Stevens Brothers, the book is available in French and English.

“If you take a look at the book, that’s a labor of love. I never imagined that it would end up with this finished professional product. It’s pretty amazing,” says Scott, Donald’s son.

“After my mother’s first visit the year before, I had the privilege of meeting Norman Stevens in 1976. It was very moving, he had a sense of having a part of his sons come back through me,” remembers Ludovic.

Don visits Normandy

“I have returned to the States several times,” continues Ludovic, “but the most memorable visit was Don’s visit to us in 2019, for the 75th anniversary of the landing. He was already 92 years old. I took a military jeep and added the colors of Paul’s regiment, a photo of the effigies of Paul, William, and Donald, and a sticker saying ‘Veteran on board,’ and we went on the road like that. We experienced completely unexpected encounters and adventures.”

Donald Stevens and Ludovic Adeline with a photo of Donald from WWII displayed in a street of Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer, in 2019. As his two brothers also have their photo on this avenue, Don dubbed it Stevens Avenue.

“Every time we stopped,” explains Ludovic, “a crowd formed and Don began to tell the story of his brothers and himself by showing their photos. As the days went by, I realized that my children and grandchildren did not know all of these details and I began to think about how to pass this story on. As comics are more accessible to young people, I brought together my entire collection of photos and transformed them into drawings.”

Donald Stevens sitting in the jeep that Ludovic, at the wheel, lovingly prepared, in Normandy in 2019.

During this most recent visit to Normandy, Donald gave Ludovic the American flag that covered his brother Paul’s coffin as well as his own Navy uniform.

Donald wanted very much to travel this year to mark the 80th anniversary of D-Day and to pay his respects again at the grave of his brother Paul, but, at 97, for obvious health reasons, he had to forgo it. It is all the more important to him that the story of the Stevens brothers be told.

Gayle E Kent

June 28, 2024

My Uncle, John “Casey” Whiteman, Jr. was in the Corps of Engineers in WWII and participated in the invasion on the beaches in France. He stayed with a French family there before he came home. They remained in contact until he died. He sent them something (I don’t remember what) every year at Christmas and they sent him a bottle of French Champagne. The bottle they sent for Christmas, 1958 was opened and served at the gathering of family after his funeral. I am sure there were a lot of these relationships. The French very much appreciated the American soldiers who fought to free them from Nazism. He was also called up to serve in the Korean Conflict. (A younger brother, PFC 1st class (Marine) was KIA in the same Conflict on 09 April 1953.) Uncle Casey survived two “wars” with only the loss of the tip of his little finger. Then died at the age of 35 (05 Sept 1959) from a ruptured aneurysm in the thoracic aorta! His older brother, 2nd Lt. George Allison Whiteman was KIA on 07 Dec 1941 at Bellows Field, TH while trying to take off, when Pearl Harbor was bombed. Gayle