Wonderful article, Thomas!! Thanks for putting this thoughtful attitude concept out in virtual print for us all to ponder. Cheers.

Intellectual Humility & Genealogy: An Answer to Family Feuds?

- By Thomas MacEntee ·

Genealogy expert Thomas MacEntee of GenealogyBargains.com discusses how practicing intellectual humility – the recognition that one’s own beliefs could be wrong – could open up the doors to genealogy research success.

And in this corner…

Intellectual humility is a mindset that is essential for critical thinking — and has more to do with genealogy than you might think.

It is likely that every genealogist has encountered a “genealogy feud” at least once during research. What do I mean?

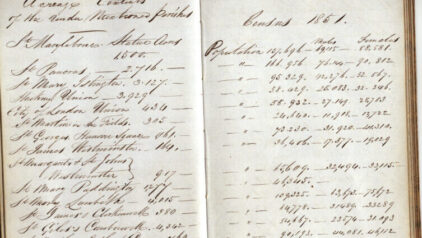

In one such scenario, I was researching the family of my uncle’s fourth wife. I received basic information via email and the focus was on the paternal grandfather who had a specific middle name. Within one hour I was able to determine the legal middle name for the man based on several birth records. I emailed this information to my relative to make sure I had the right target person since the birth date and location aligned… but with a different middle name.

Let’s just say that it was the shortest amount of research I ever did for a family request. The response was vitriolic and mean-spirited. I was told that “his middle name was always _______,” and “we have family stories about his middle name,” and “you don’t know what you’re doing. And you do genealogy as a profession?”

I opted to back out of the project and told her that if she wanted, she could use the information I provided to research on her own. And I never heard back.

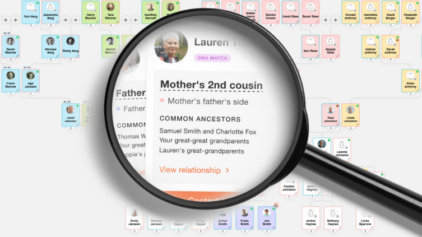

Another scenario: you’re updating information on a tree at MyHeritage, complete with source citations. And another user contacts you to share your tree in order to collaborate since you have ancestors in common. The user keeps changing information, overwriting your updates, and without any proof. You send messages to the user explaining the rationale behind your updates, to no avail. A passionate conversation takes place in a series of messages, but you and the user cannot come to an agreement on some of the facts. You decide to change the access rights for the user so they can no longer update your tree at MyHeritage.

Is there a common thread in these scenarios and similar ones? It has nothing to do with one researcher being “right” or having more experience. Instead, it likely has more to do with intellectual humility.

What is intellectual humility?

Put simply, intellectual humility is the ability to realize that your beliefs or opinions might be wrong. Further, it also involves the recognition that your knowledge could be limited and that bias could impact your beliefs.

Face it, it isn’t easy admitting that you might be wrong. That is the crux of intellectual humility, but there is much more to the concept. It isn’t exactly open-mindedness, which deals with being open to new information and ideas, but it is related. Intellectual humility is focused on current beliefs and opinions.

Think of it as overconfidence in one’s intelligence about a subject. Admitting to intellectual gaps is practicing humility… being open to the idea that your opinion may need to be re-examined.

And if more of us could practice intellectual humility, would it offer the opportunity for better communication and conflict resolution?

The benefits of intellectual humility

To be honest, thinking is hard work. There are some nights at home that, when it comes to selecting a movie to stream, my brain is just tired. I don’t want to watch a film noir movie or one with a non-linear timeline. I want something fluffy and funny.

Practicing intellectual humility takes work and perhaps this is why many of us don’t want to work on improving how we come to believe something. Here’s why you might want to do the work:

- Your decisions take on a better quality and solidity. They are rooted in different types of information from different perspectives.

- You are better able to recognize and accept limits to your intellect.

- You are able to engage in more positive interactions with others when you can admit that you might be wrong.

- You become more open to learning from a variety of sources.

- Conflicts are fewer and you are less polarized when it comes to discussions.

- You become more open to collaborating, even with those who hold different opinions.

- Admitting that you don’t know everything about a topic allows you to become better at researching information, evaluating that information, and possibly updating your opinions.

Putting intellectual humility into practice: a Place of “I Don’t Know”

Would you be open to being more realistic about your views? What would it take to get there and to practice intellectual humility?

I often think of a quote attributed to Alfred Einstein: “The more I learn, the more I realize how much I don’t know.” And if you’ve attended any of my genealogy lectures, either in person or virtually via webinar, you know I’m never afraid of responding to a question with “I don’t know. But let me try to find out for you.”

I call it “putting myself in A Place of I Don’t Know.” And it is a strategy I often use when confronted with a brick wall, either for my own genealogy research or that of a client. It means removing all my preconceived notions, my biases, even my prior research and going back to the beginning.

If you’re familiar with The Genealogy Do-Over project — where I put almost 40 years of family history research aside and started over with myself and then researching my parents, grandparents, etc. — then you’ll understand that the premise is based on practicing intellectual humility.

After struggling with a messy, undocumented family tree which was very tall but had shallow roots, I said enough. I admitted my mistakes, admitted I had been a “name collector,” but had no regrets about past research indiscretions. It was time to move on, start anew, and build a family legacy… a tree that might not be as tall with lots of ancestors, but with solid roots forged from evidence evaluation and source citations.

Conclusion

In the two genealogy feuds described in the opening of this article, a resolution could be reached if one or even both parties practiced intellectual humility. I should have realized that my relative was driven by the sentimentality of a family story and that fighting over the legal middle name shouldn’t prevent either of us from pursuing further research.

As for the family tree fight, I realize that I should only have given the related user “view” rights to my tree at MyHeritage so that they could see my updates and then engage in a conversation via messages. I also should have been open to my data being incorrect and verifying my research. Since the user had some solid data about one of my ancestors, they could be sitting on more information, including family photos. I never want to “burn a bridge” that could give me access to future research opportunities.

After over 45 years of searching for my roots, I leverage the skills of critical evidence evaluation and documenting proofs via source citations but with intellectual humility. These skills were never intended to be weapons, used to brow beat other researchers just because I think I have many years of experience or I know more. That intellectual overconfidence can often act as poison and eliminate opportunities for collaboration and further research.

Further reading

The JSTOR DAILY blog recently published a series of articles about intellectual humility and its role in faith, artificial intelligence, medicine, and more.

- Can Intellectual Humility Save Us from Ourselves?

https://daily.jstor.org/can-intellectual-humility-save-us-from-ourselves/ - What Is Intellectual Humility?

https://daily.jstor.org/what-is-intellectual-humility/ - Doing Math with Intellectual Humility

https://daily.jstor.org/doing-math-with-intellectual-humility/ - Come Let Us Argue: Faith and Intellectual Humility

https://daily.jstor.org/come-let-us-argue-faith-and-intellectual-humility/ - Second Opinions: On Intellectual Humility and Medicine

https://daily.jstor.org/second-opinions-on-intellectual-humility-and-medicine/ - Drinking with Intellectual Humility

https://daily.jstor.org/drinking-with-intellectual-humility/ - What if AI Operated with Intellectual Humility?

https://daily.jstor.org/what-if-ai-operated-with-intellectual-humility/ - Intellectual Humility: Foundations and Key Concepts

https://daily.jstor.org/reading-list-intellectual-humility-foundations-and-key-concepts/

In addition, if you are interested in putting intellectual humility in practice while researching your roots, check out The Genealogy Do-Over at https://genealogybargains.com/genealogy-do-over-start-here/.

Jean Foster

March 26, 2024

Very interesting and useful article. Thanks for the info on JSTOR to follow up with more reading. I seem to have the same problems and find this as as way to help all of us.

Thanks Thomas.