This guest post has been written by expert genealogist Miriam J. Robbins. Miriam has been instructing and lecturing in the United States since 2005. She has been interested in her family history since she was a young girl, living in Southeast Alaska. She began her genealogy research in 1987, and ten years later was successful in reuniting her grandmother with her biological family. Miriam writes an award-winning genealogy blog, AnceStories: The Stories of My Ancestors, and keeps busy adding links to her Online Historical Directories and Online Historical Newspapers websites.

This guest post has been written by expert genealogist Miriam J. Robbins. Miriam has been instructing and lecturing in the United States since 2005. She has been interested in her family history since she was a young girl, living in Southeast Alaska. She began her genealogy research in 1987, and ten years later was successful in reuniting her grandmother with her biological family. Miriam writes an award-winning genealogy blog, AnceStories: The Stories of My Ancestors, and keeps busy adding links to her Online Historical Directories and Online Historical Newspapers websites.

The month of October is known for Family History Month as well as the holiday of Halloween. What better combination of the two than to learn about death records in genealogical research? Death records are one of the first and best types of records used in beginning genealogical research because of the variety of formats in which they appear, the basic facts which they contain, and the immense details that many list about both the decedent’s life and death.

It’s important to learn a little about the history of death records in your ancestor’s location, as it will help you understand how the facts were gathered and recorded, what information the records may contain or omit, why the records themselves may be missing or difficult to find, and where to locate the death records currently.

For instance, the state of Michigan’s first statewide vital records registration, which began in 1867 and continued until 1897, required both birth and death records to be collected and recorded, census style. The township supervisor or city assessor had to canvass their areas preceding the first Monday in April to determine which births and deaths had occurred the year before. Just as in a census, this left many gaps, as a family could have moved away or an elderly person could have died leaving an empty home with no one to officially report the events to the officials when they came by in the spring. In the Netherlands in the 1800s, it was the custom for two witnesses or neighbors to report a death with the local municipal clerk shortly after the death occurred. When civil registration began in Ontario, the local doctor or a family member often registered the death with the county.

There are several places where you can learn about the history of vital records–and specifically, death records–in your ancestor’s location. The first may be at your local genealogical library, which may have how-to research books of your ancestor’s location, even if your current community is not the same location.

In Europe and the Americas, vital records registration often was begun by religious institutions, particularly the state church (Catholic, Lutheran, Reformed, etc.) in Europe or South America, or the local community churches in North America’s cities and villages. Death records typically were not kept at first, but burial records were, giving a close approximation of the date of death, typically preceding the burial by a few days. Even if your ancestor was not a Christian or of a different denomination than the local church, it might be worthwhile to check with that local church’s burial records for the time period in which he or she may have died, to see if mention was made of their death. Some of the reasoning for this is that often the local priest or minister may have been one of the few literate people in the community, and was thus the unofficial community historian. In other cases, the state church was considered the only official recorder of vital records, and it was required to register the events with that church even if you weren’t a member.

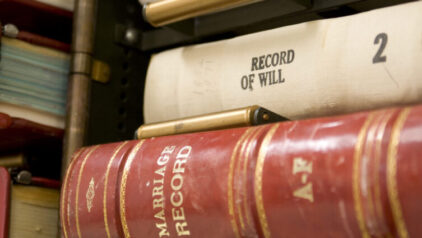

As time went by, many national, provincial, or state governments began civil registration. There were a variety of ways in which deaths were recorded. Some of the early records may have been simple hand-written notes of the name of the decedent and his or her date of death. Others were recorded using “boilerplate” or standard language, listing all the pertinent and required details. Even if these are written in a different language than your own, the boilerplate language of these documents makes it fairly easy to figure out using a translation tool such as Google Translate (http://translate.google.com), especially if you are looking at several death records at once. The death records in civil registration were often bound in very large books called libers (see image below). Over time, many clerks moved away from using hand-written, boilerplate language records and used preprinted forms spread across the two pages, ledger-style. Nineteenth-century death records often included the following details:

- the name of the decedent

- the date (and sometimes, time) of his or her death

- the place of death

- the cause of death, if known

- the age of the decedent, often given in years, months, and days

- the marital status of the decedent

- the names of the decedent’s parents, if known

- the birthplace of the decedent

- the date the information was recorded

Do you see how useful this information could be? It’s especially helpful considering that vital records (both births and deaths) usually began to be recorded at the same time in a certain place. For instance, in Washington State where I live, vital records registration began in 1907. If a woman who died in Washington in 1910 had also born in Washington in 1873, she would not have had a Washington birth record. However, their death record would give her birth date and place, thus providing an alternate source for a birth record.

Netherlands, Friesland, burgerlijke stand, Overlijdensregister 1888, Ferwerderadeel, Aktenummer A20, Wieger Tjammes Valk, Allefriezen (http://www.allefriezen.nl : accessed 3 October 2014).

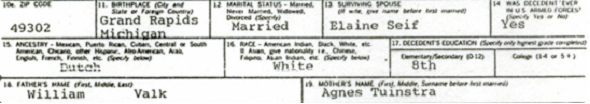

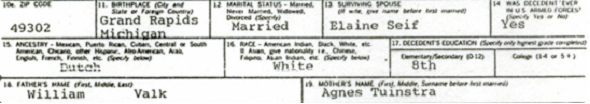

Eventually, the national or local governments in many countries began issuing certificates of death to surviving family members. These certificates contain a great many more details than the ledger-style records. These details provide many facts as well as clues to other types of records that you can research. Below is a detail from my maternal grandfather’s death certificate:

State of Michigan, death certificate no 0130610 (1989), William Valk; Department of Public Health, Lansing.

This detail states the ZIP code of my grandfather’s residence, his birthplace and marital status, his wife’s maiden name, and that he had served in the U.S. Armed Forces. His ancestry is given as Dutch, his race is White, and he had an 8th-grade education, typical of his generation. This also gives his father’s name and his mother’s maiden name. These details could lead me to search for his marriage record, his military records, the local heritage societies, school records, and vital records for his parents and wife.

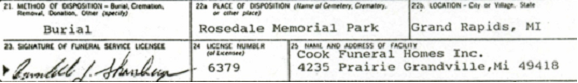

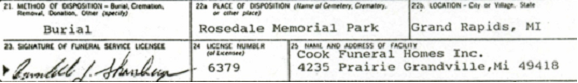

State of Michigan, death certificate no 0130610 (1989), William Valk; Department of Public Health, Lansing.

The next details provide the name and location of the cemetery in which my grandfather was buried, as well as the name and the funeral home which took care of his body. Contacting these two businesses would likely provide me with even more information.

Keep in mind that one signature you’ll never see on a death record is the decedent’s! In other words, dead people don’t give the information that goes into their own death record. The informant may be ignorant about where the decedent was born or the names of his or her parents. When the informant is a family member, grief can fault their memory as well. There is always room for simple errors like misspellings or transposed numbers, as well as misunderstanding the information given. Occasionally information is willfully falsified. Regardless, remember that analyzing the information you have and comparing it with other documents will help you determine the validity of each piece of evidence you find within the death record.

Death records are a great start to your genealogical journey. They also are good documents to revisit, gleaning every little detail from them and using them as springboards for more investigations into other areas of your ancestor’s life. You’ll soon discover that death records are definitely “vital” to your research!

Have you uncovered anything interesting in death records? Let us know in the comments below.

John Wood

October 6, 2014

Nice article; thank you for writing it.

I completely agree that death records are a PRIMARY source of information. The version I love to find are “obituaries”, usually found in a local newspaper. I have found these to be written by a close family member, and to contain a “treasure-trove” of new leads to follow up on. In the case of a prominent person to the local community, I have often found them to be researched and written by a staff member of the newspaper itself, which will add fantastic tidbits you may not have otherwise uncovered. Those records are real “jewels” to me!

Although I have been doing this “off-and-on” for more than 20 years, I do not feel I have been very successful at it. My worse roadblock has been that my grandfather was “adopted” in the early 1900’s.

“Common family knowledge”, (how reliable is that, eh?), has it that my grandfather and his older brother were actually fathered by my great-grandfather, but with his mistress, not his wife, brought into the family and raised by the wife! Handwritten birth records at the tiny town hall of their birth “seem” to support this theory by the actual “scratching out” of their mothers name on the pages! I need to find another official record of their birth in the 1895-97 time frame…

That family, my paternal great-grandfather and great-grandmother have MANY interesting incidents to be found through their entire history together; MANY mysteries yet to be unwoven! I am working on it!

Thanks again for an interesting article.